Myriam Ben Salah. Photo Saskia Lawaks

Myriam Ben Salah. Photo Saskia Lawaks

To say that Myriam Ben Salah’s appointment as director of the Renaissance Society, a highly influential museum within the University of Chicago, got lost in the news cycle on April 22, 2020, is an understatement. Coronavirus deaths in the United States had surpassed 45,000; the New York Times had front page stories on the Senate passing a $484 billion relief package and on how the pandemic made its way from Wuhan to Seattle. Ben Salah’s actual start date, in September of that year, was similarly overshadowed, and the Ren, as it’s known familiarly, would remain either closed or open by appointment only for months. (Not that Ben Salah wasn’t busy; even as she geared up for her new role, she was co-curator, with Lauren Mackler, of the Hammer Museum’s fifth edition of “Made in L.A.” biennial, which was rescheduled to begin in July 2021.)

This past week, the Tunisian-born curator who came to the Ren from a curating role at Paris’s premier museum for groundbreaking contemporary art, the Palais de Tokyo, opened the doors to her first exhibition at the Ren—a group show, titled “Smashing Into My Heart,” broadly based around the idea of friendship. She spoke with ARTnews editor Sarah Douglas about how art is shown and who experiences it, friendship, and renewing one’s faith in contemporary art.

The Renaissance Society is an interesting institution. It’s small, physically, but has a large footprint in terms of its influence as a non-collecting kunsthalle. In a recent interview with Chicago publication New City Art, you brought up the fact that there’s a lot of focus on what’s shown in museums, but that the question of audience is often left out.

I think museums recently have been sort of divorced from the audience. They may be showing more diverse works and making efforts on that side, but they are showing them to the same population and not really making any effort to get a new audience within the walls of the museum. There is this whole discourse around justice and equality and diversity. And I feel like sometimes these concepts are empty shells because they seem to be there for publicity and for virtue signaling. There is a disconnect between that and the audience that institutions are catering to. It’s a question that’s important to me. It’s something that I had started thinking about earlier, and especially when Lauren Mackler and I were working on “Made in L.A.”: This idea of not only where to show art but how to show it in order for it to break from the language of contemporary art and the contemporary art world as we know it.

The Ren is on the fourth floor of an academic building in the University of Chicago, so we will never get walk-ins. And we’re also showing artists that most people haven’t heard of. So it’s very difficult for the Ren to have, let’s say, a spontaneous audience. In a conversation between [former Ren directors] Suzanne Ghez and Hamza Walker, it came up that the term audience is a little bit misguided in regards to the Ren because, with an institution like this, you can’t really target an audience, you have to build your public. Our public is students who go to the University of Chicago, students who are learning about art, and some other artists in the community who looking to be introduced to other types of works or have come to see the works of their colleagues. So, we have a very specific role in that sense.

That being said, we exist within a certain environment, which is the south side of Chicago, and it is a missed opportunity to be completely divorced from that context. The Ren will never make a big statement about outreach or engaging audiences or things like that, for the reasons I mentioned before: I think the more communication there is, the less action. We’re trying to have very targeted, small, tangible actions. We’re thinking about partnering with an elementary school and have one teacher bring their class to the Ren for every exhibition to have a continuing dialogue. That is one way we can start engaging and maybe creating a ripple effect of having people in the area come once in a while and learn about these artists in an organic way. Our size allows us to do that; we don’t have the same stakes as bigger institutions.

You have come into this job at a very particular time, as coronavirus was emerging. You were also working on “Made in L.A.” during the same period. I’m really curious what your thoughts are on how institutions are going to continue to toggle between the physical and the virtual.

One of the first things that I had to deal with at the Ren was our annual gala, which is a fundraising event. We decided that we would go virtual. Where we always go first is the artist’s needs. I was having conversations with artists and they were saying that since the start of Covid they were asked to provide content for the Internet all the time, but without being paid for it, and without any real thinking behind it. So I thought, “You know what? We have this opportunity of doing something virtual. Let’s not do a simple benefit on Zoom. Let’s find a sponsor, create a platform and make it useful for artists.” So we did “Renaissance TV,” which launched for our benefit with a 24-hour marathon of videos. Some were produced for the occasion, some were existing things. That allowed us to reach an audience that was all over the world and that exceeded the footprint of our institution. But it was also great because I think artists really appreciated the way it was structured and also the way that it could be a long-term platform for commissioning new moving image works.

I definitely think these types of platforms will continue growing because it responds to the need to tame the Internet and to make it work for art institutions. But I don’t think things that exist in the [physical] space can migrate online. There is something about experiencing an artwork, about being in the space with someone else and with the specific artwork. Giving access to collections online can be very informative, but I don’t think it can replace the experience.

View of the exhibition “Smashing into my heart,” at the Renaissance Society, 2021. Photo: Useful Art Services

View of the exhibition “Smashing into my heart,” at the Renaissance Society, 2021. Photo: Useful Art Services

You’ve talked about how a lot of your work comes out of a dialogue with artists. I interviewed an artist during the pandemic who said something that really stayed with me: they were doing this commission, and because of lockdowns and resulting delays, they had more time to complete it. And they took the time to create the project. They didn’t finish the project and sit down and chill. I wondered if it’s something that you have noticed among artists: that they’ve been able to slow down.

We definitely saw that when we were working on “Made in L.A.” Time became such a weird element in our process because the show kept being postponed. And so we had this elastic period where artists had more time, but also fewer resources because many businesses were closed. It made it difficult for them to work and many projects had to adjust. So, we witnessed this adaptability of artists who not only took the extra time that they had, but also really adapted to the circumstances. I’m really thinking through these transformations and the limitations that the pandemic placed upon museums and the circulation of art into space, and the ability to gather in a certain space and produce something. The pandemic took the artists out from this crazy rhythm of producing for galleries and maybe connected them to their practices more, and gave them time to find the intersection between their practice and the current moment.

And once artists are on that treadmill and they get known for a certain kind of art—they’re still young, but they can’t evolve to the next thing because suddenly everyone’s watching.

Yeah, absolutely.

In another recent interview with Chicago’s Hyde Park Herald, you talked about how art had become more political in content in recent years, but what you think actually needs to be addressed is “the way we make art, the way that we circulate art, the way that we show art. It’s not just a consideration of who we’re showing in the art space or what gets represented, but also who we’re showing to and how we are showing it.” Can you expand on that?

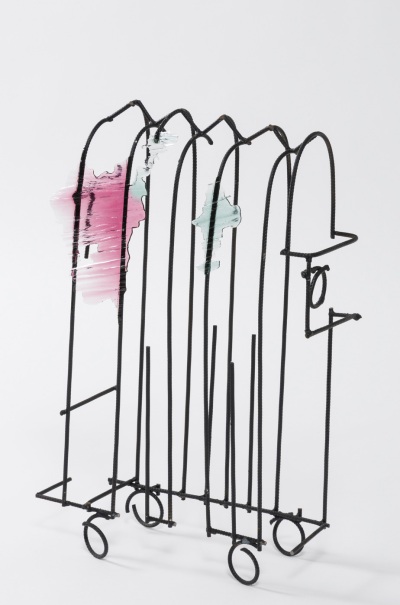

Neil Beloufa, Untitled (Radiator), 2016. Courtesy the artist and Francois Ghebaly Gallery, Los Angeles

Neil Beloufa, Untitled (Radiator), 2016. Courtesy the artist and Francois Ghebaly Gallery, Los Angeles

I was trying to be mindful of the question of representation and that representing politics is not enacting politics. I don’t think showing an issue is necessarily doing anything about it. I’m interested in practices that are aware of the place that they have within the world—sustainability, for example. There is a lot of artwork and exhibitions dealing with questions of the environment, sustainability, et cetera. But art production is, as you know, a disaster for the environment. It is tricky to point out the failings of other fields on the environment without really looking at ourselves and what we do. Some artists are aware of it and integrate that awareness into their work. And some artists don’t need to talk about it, but are very respectful in the way that they produce their art or in the way that they circulate it. They have an ethic within their studios. Neil Beloufa is someone I’ve known for years and I’ve really seen his process evolve. Neil is really aware of the contradictions of his place in the world as an artist. He’s someone who has tried to create a system within his studio where everyone, including himself, is paid the same. Of course he’s the one getting an exhibition, but everyone in the studio has an equal place, et cetera. That’s not visible in his work. It’s not something he advertises. But it’s interesting to see how the process becomes almost more political or more ethically grounded than what the work represents.

Is it important to convey that to an audience?

The audience is in contact with the artwork. The rest of it is more of an institutional concern, I would say. Being at the head of an institution, I feel the need—even more so than before the pandemic—to work with artists who take risks to reinvent their practice, constantly formulate their own language to create a syntax, that’s at the intersection of their personal, imaginary, and the world that we live in, and who really propose new ways of thinking, of making, and of being in the world. Artists who are not afraid of non-linear advice and who are not responding to the expectations that are placed upon them.

The exhibition you just opened at the Ren is about friendship. The institution of friendship has been really affected by this pandemic.

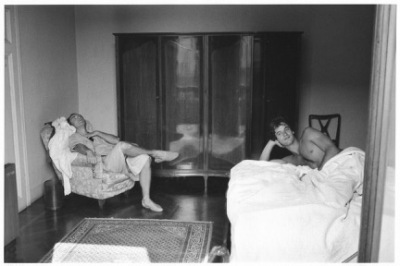

Herve Guibert, Han Georg et Thierry a Montecatini, 1983. Courtesy the artist's estate and Callicoon Fine Arts, New York

Herve Guibert, Han Georg et Thierry a Montecatini, 1983. Courtesy the artist's estate and Callicoon Fine Arts, New York

Definitely. It’s a show that came out of something rather personal, but I hope it can expand and reach a broader context. Not long ago, when [art critic] Bruce Hainley asked me to teach a class at Art Center in Los Angeles on Zoom, he said, “Pick a subject that you think a young artist should learn about.” Spontaneously, friendship came to mind. Maybe because I was also recently reading Mathieu Lindon’s 2011 book Learning What Love Means, which tells the story of his friendship with Michel Foucault and the circle around him at the time, which brought me to Foucault himself on friendship as a way of life. I started thinking about friendship as a relationship that is outside of institutions. And I was also reading this amazing, amazing book of poems by Danez Smith, about the saving grace of a friendship, and the title of the exhibition, “Smashing Into My Heart,” comes from there.

Speaking of Foucault, during the pandemic I read Herve Guibert’s book To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, which is very much about Guibert’s friendships, in particular with Foucault, during a time of trauma, specifically resulting from the AIDS epidemic.

Herve Guibert, Les Amis, 1982. Courtesy the artist's estate and Callicoon Fine Arts, New York

Herve Guibert, Les Amis, 1982. Courtesy the artist's estate and Callicoon Fine Arts, New York

Absolutely. It’s interesting that you put those things in relationship because I was going to say that in addition to these cultural elements that brought me to thinking about friendship, it was also prompted by a year of being stranded in the United States and relying exclusively on friends for both emotional and material support. It’s really made me learn what friendship means as a praxis and as a way of acting and being in the world. And from there, I decided to put together this exhibition not as an exhibition that considers friendship as a subject, not with artworks that deal with friendship—I think that would probably be boring—but instead as an exhibition that uses friendship as a premise to think about art. There are many things in common between friendship and art. Friendship can be both a condition for art making and a model for art. Both friendship and art escape classification. They both have their complexities and are non-linear. I was interested in seeing how artists would consider friendship as an esthetic practice.

Tell me about an artwork in the show that exemplifies all of this.

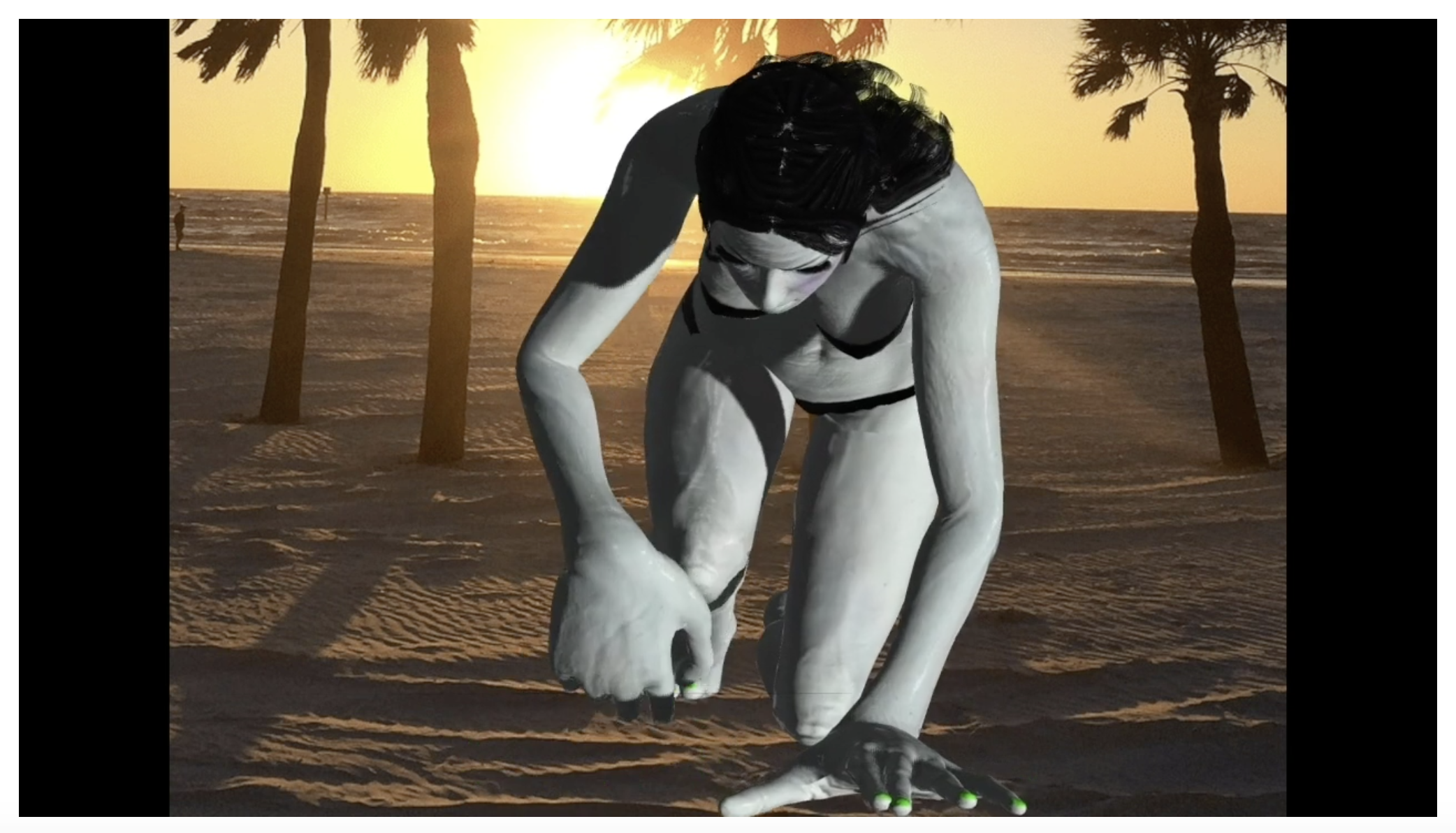

Ceal Floyer’s sound piece, Me/You (Love Me Tender), from 2009, is an excerpt of the Elvis Presley song “Love Me Tender,” where all the words have been cut except for “me” and “you.” You have these very long silences between me and you—the void becomes palpable. And that’s interesting right now, because it materializes the separation between people. There’s an artwork by Tita Cicognani, a much younger artist, an amazing video titled, I Am So Full of Longing and Desire It Gushes Out of My Knees as They Scrape the Ground Upon Which I Crawl Toward You. She made it in 2020, and you can really feel that it’s a film that comes from this period of separation and longing and isolation.

Tita Cicognani, I Am So Full of Longing and Desire It Gushes Out of My Knees as They Scrape the Ground Upon Which I Crawl Toward You, 2020. Courtesy the artist

Tita Cicognani, I Am So Full of Longing and Desire It Gushes Out of My Knees as They Scrape the Ground Upon Which I Crawl Toward You, 2020. Courtesy the artist

Last year, you told Artforum your top ten favorite exhibitions of 2020. There was a line in your entry on Tishan Hsu’s show at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles that really struck me because it’s an experience that I myself have from time to time. You said, “Usually, about once a year, I lose faith in contemporary art. Then I come across a practice that makes me start believing again.” It’s takes guts for someone in your profession to admit to that.

I like being candid about the profession. I feel like I have a certain distance from the art world where I always have a foot in and a foot out. It’s very important to preserve that. So, I that’s why I allowed myself to say that. And it’s completely true. Something that makes me believe again is the artists I’m working with right now. All the dialogue is bringing me back to life. I’ve had a long and ongoing dialogue with Meriem Bennani. She’s definitely someone whose whose practice reminds me why I’m doing this job. She’s really taking risks and questioning what she does all the time and always trying to go one step forward. We’re producing this new, very ambitious film with her dealing with displacement, biotechnology, and privacy. Also, we have collaborated with SculptureCenter [in New York] on a project with Diane Severin Nguyen. She made this new movie that she shot in 2020. The conditions for shooting it were so complicated, we had to send her to Poland and go through a thousand loopholes to make that happen. But it’s really exciting. She’s a great thinker and writer. Being in dialogue with her is humbling. I try to work with artists who are going to teach me and constantly renew my faith in contemporary art.

The Ren has quite a long history.

And the board of directors are really attached to the identity of the Ren and its history. That is truly amazing and gives me such a great playground to make new things happen. What can I do in a space that has seen one hundred years of exhibitions? It will come from conversations with artists. I had this conversation with [LAXART director] Hamza Walker and he said, “you know what, I know you’re going to take risks of your own and you might fail, but I’m more interested in your failures than in somebody else’s success.” This notion of not being afraid of failure is interesting. So, yes, I hope there will be successful failures in my time.

It’s like when the teacher says, “Do you make mistakes?” and the student says “Yeah.” And the teacher says, “Good, I want you to make mistakes. That’s the only way you learn.”

I think it’s important to make mistakes. That’s something we allow artists to do here too. I think that’s one of the specificities of the Ren: being open to artists making a mess and figuring things out and not having things all explained and ready.

There is a collection of Clement Greenberg’s essays and in the introduction he says he had a chance to re-edit the pieces, but he didn’t. He wanted people to read them as they’d originally been published, because he was proud of having “learned in public.”

Learning in public is a great way to put it. I identify a lot with that.

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/myriam-ben-salah-renaissance-society-interview-1234604317