COVID-19 patients who required life-support late in 2020 were significantly more likely to die within 90 days than those who were placed on it during the pandemic’s first wave, a new study suggests.

Researchers from the University of Michigan Ann Arbor found a sharp decrease in survival rates of patients placed on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), a system used for patients in critical patients and assists in the circulation of blood.

They found patients placed on ECMO early in the pandemic survived for at least 90 days in 63 percent of circumstances.

Later on, however, the survival rate cratered by 40 percent, with less than half of those placed on ECMO from May to December 2020 surviving 90 days.

The researchers believe the sharp increase in deaths due to poor resource management with ECMO.

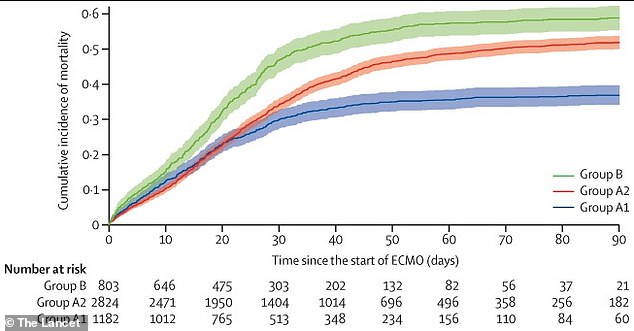

Researchers found that patients placed on ECMO early in the pandemic (blue line) had significantly lower 90-day mortality rates than those placed on life-support afterwards (green and red lines)

Researchers believe hospitals could have managed resources better in the second half of 2020, avoiding using valuable resources on patients that were going to die anyways. Pictured: a physician assists a Covid patient in a Farmington Hills, Michigan, hospital on December 17

‘What we noticed right away is that the patients treated later in the pandemic were staying on ECMO longer, going from an average of 14 days to 20 days,’ said Dr Ryan Barbaro, co-first author of the study and intensive care physician at Michigan Medicine, in a statement.

‘They were dying more often, and these deaths were different

‘This shows that we need to be thoughtful about who we’re putting on ECMO and when we’re making the decision to take patients off who aren’t getting better. Across the U.S. right now, we have places where ECMO is a scarce resource.’

For the study, published late last month in The Lancet, data was gathered from 4,800 patients from 41 countries.

The patients were separated into three groups, one for patients who received ECMO before May 2020 in hospitals deemed ‘early adopters’.

A second group was for patients placed on ECMO after May at those same early adapter hospitals.

The third group was patients placed on ECMO after May in hospitals that did not use the life-support system earlier in the pandemic.

Just over a third, 37 percent, of people placed on ECMO in the first early adopter group died within 90 days of being placed on the system.

The figure increased to 52 percent in the same hospitals between May to December of 2020.

In hospitals that were not early adopters, 58 percent of patients died within 90 days of receiving ECMO treatment.

Placing a patient on ECMO is a very intensive process that can absorb many medical resources.

The system itself requires many materials, such as tubes, pumps and oxygenators, and the patient must remain under supervision of medical professionals.

All of these resources being invested into patients where they might not be effective hurts the entire hospital – and all the patients admitted there.

Patients who were placed on ECMO after May 2020 were also more likely to have been given non-invasive procedures like receiving drugs like remdesivir and also having been placed on a ventilator – also requiring a lot of hospital resources.

Doctors will do whatever they can to make sure a patient survives, no matter how many resources are expended, but in times where there is not enough to go around tough decisions must be made.

Patients who have family members present are also more likely to receive the more intensive treatments because they have people advocating for them to doctors.

The researchers want hospital systems to set clear guidelines for when a patient receives resource intensive procedures in order to make better use of limited resources.

Hospitals should also work to help each other out to solve resource shortages.

‘In these moments of crisis, our ability to meet demand presents ethical challenges, and COVID has drawn out the weaknesses in our system, as well as showing how those with resources and relatives who can advocate on their behalf are more able to find out about ECMO and seek the opportunity for their loved one to be treated,’ Barbaro said.

‘Meanwhile, hospitals in non-surge areas need to reflect on what policies and procedures they’ll use if they experience another surge, to foster ethical allocation when resources are constrained.’

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-10080983/COVID-19-patients-placed-life-support-late-2020-40-likely-die-90-days.html