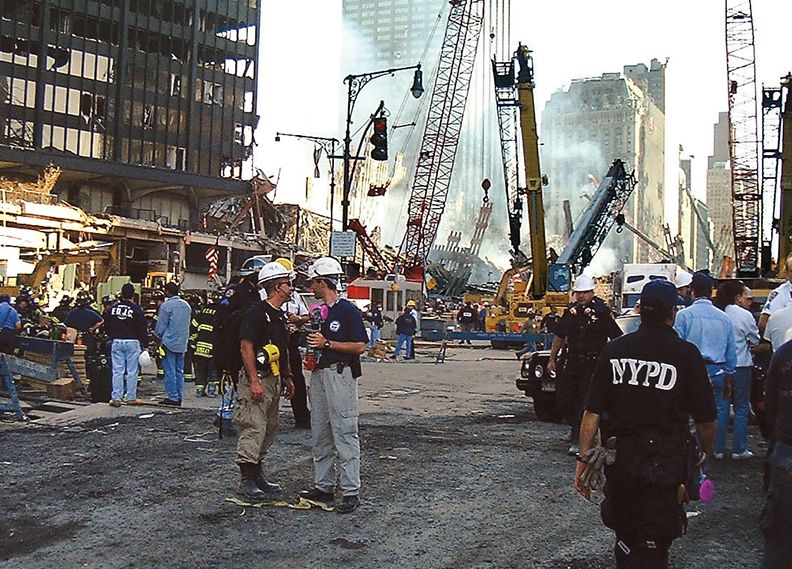

A New York firefighter’s baseball cap hangs in Dr. David Marcozzi’s office, reminding him what’s at stake. Marcozzi, who is now the chief clinical officer at University of Maryland Medical Center, arrived outside of New York City a day after planes crashed into the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, 2001. He was tasked—as a member of the Rhode Island Disaster Medical Assistance Team under HHS’ Disaster Medical System—with treating and transporting first responders and civilians injured by the falling rubble. Marcozzi helped a firefighter, who gave him his hat as thanks. The blue, red and yellow “FDNY Bravest” cap is still covered in dust that engulfed Ground Zero. “That shaped us all. It’s an event none of us will ever forget,” he said. “It’s even more palpable now, how we all unified against one threat to be the best we could be.” Marcozzi remembers watching New Yorkers proudly raise flags as he drove through the city, how people helped each other and bonded in solidarity. “I think we’ve lost some of that,” he said. “I’m frustrated by the lessons that have been documented but not learned. All lives that have been lost, whether during COVID-19 or 9/11, are a reminder for us as survivors to be better the next time. It is on us to build resilience in healthcare that allows us to save more lives.”

“I’m frustrated by the lessons that have been documented but not learned.” Dr. David Marcozzi, chief clinical officer at University of Maryland Medical Center.

Underfunding prevention While hospital emergency preparedness has improved over the past two decades, progress hasn’t matched the growing threat of natural and man-made disasters. An increase in funding and an “all-hazards” approach to readiness would help close the gap, industry observers said. “The best money spent in healthcare is prevention, but I know prevention isn’t well funded in healthcare,” said Dr. David Markenson, medical director at the Center for Disaster Medicine at New York Medical College. Federal authorities directed post-9/11 funding toward lab testing, health surveillance and epidemiology, community resilience, countermeasures and mitigation, incident response and information gathering. But funding has waned over time. Appropriations for the Public Health Emergency Preparedness program have declined 26% since 2003, or 48% when accounting for inflation, according to the Trust for America’s Health. That has poked holes in the public health safety net. There’s a $4.5 billion annual shortfall in public health spending, the National Health Security Preparedness Index estimates. As a result, many state and local public health agencies lack the staffing levels and technology infrastructure to combat existing health threats and prepare for emerging ones.

COVID-19 has claimed more than 640,000 American lives. Measles cases hit a 27-year high in 2019. Mass shootings have become alarmingly commonplace. Unseasonable cold and heat are straining an ill-equipped infrastructure. Fires, floods and hurricanes are more frequent and intense. While hospitals have boosted their surge capacity over the past 18 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, their readiness only marginally improved from 2005 to 2014—the most current year available—per the Hospital Medical Surge Preparedness Index, which the American Hospital Association uses to measure the size of medical staffs, the number of hospital beds, the amount of equipment and supplies, and systemwide coordination strategies across 6,200 U.S. hospitals. There was little or no difference in most states’ scores over that period, Marcozzi and his peers revealed in a recent study published in the Journal of Healthcare Management. They also matched the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care data to population information to gauge how readiness initiatives size up to their respective service areas. “HMSPI scores are increasing. But if we wanted to advance our preparation to a level at which we would all want as healthcare providers or patients, we have a fairly long way to go,” Marcozzi said. Other metrics reinforce that narrative. The U.S. scored a 6.8 on the 10-point scale of the National Health Security Preparedness Index as of the end of 2019. It analyzes 130 different criteria for each state including the prevalence of hazard planning in nursing homes, the number of paramedics and medical volunteers, the degree of community engagement, the level of information management and infrastructure quality, among others. That was only a 1.5% boost over the previous year and an 11.5% increase since the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention launched the index in 2013. At the current pace, it will take a decade to reach a health security level of at least 9. The pandemic exposed a public health system hollowed out by continued underfunding. Some states did not have plans to accommodate a surge in public health testing nor require coordination between private and public labs. Only 44% of local emergency medical services agencies participated in regional healthcare coalitions, the National Health Security Preparedness Index found. Reserve staffing registrants via the Medical Reserve Corps ranged from less than 10 per 100,000 population to up to 280 across states. More than 35% of nursing home residents received care in a facility that has been cited for deficiencies in infection control practices, according to the National Health Security Preparedness Index. “The improvements in preparation we have seen in recent years aren’t fast enough to keep up with the growing array of threats,” said Glen Mays, chair of health systems, management and policy at the Colorado School of Public Health at the University of Colorado and director of Systems for Action. “We need to look at ways to expand federal funding for preparedness activities. The market forces that hospitals face run counter to making long-term investments for uncertain events.” Disasters, unfortunately, seem far more certain. Over the past two decades, wildfires have more than doubled in size, scorching an average of 7.4 million acres annually in the U.S., according to statistics from the National Interagency Coordination Center. Wildfires only burned around 2.9 million acres a year in the ’80s and ’90s. California experienced another historic fire season in 2020 when five of the six largest wildfires since 1932 burned though the state. Meanwhile, more hurricanes made landfall in Louisiana in 2020 than any other year. “We need an all-hazards approach to preparation—infrastructure for surveillance, communication outreach always running in the background, regular check-ins with special needs registries,” said Dr. Karen DeSalvo, chief health officer at Google. “The list goes on and on—these are foundational capabilities.”

COURTESY OF DR. DAVID MARCOZZI

COURTESY OF DR. DAVID MARCOZZI

Members of the Rhode Island-1 Disaster Medical Assistance Team stationed near Ground Zero on Sept. 12, 2001.

A hard rain’s a-gonna fall Shortly before Hurricane Isaac pummeled Louisiana in August 2012, DeSalvo was checking names off the state’s special needs registry, which identifies people who may need extra help during an emergency. The then-New Orleans Health Commissioner met a wheelchair-bound veteran who managed several chronic conditions. His subsidized high-rise apartment complex lost power, which meant that he had been there for a couple days. He was hoarding food and water, like many of his neighbors. “It wasn’t because a storm was coming; he had to live like that all the time. Our most vulnerable are always living on the precipice of disaster because they can’t get to where they need to for help,” DeSalvo said. “I found myself angry—we live in a system where a person has great health coverage, but the only person that went to help them was a health department director when the VA had the resources to help. We cannot and should not do this alone.” That, in part, spurred New Orleans’ Empower Initiative, which features a geocoded map that uses Medicare data to inform first responders about who’s most vulnerable when disaster strikes. “I was thinking I was doing all this good for public health, but the people who need you most don’t even know you exist. Maybe that’s one of the reasons I feel an obligation to amplify the messages and profile of public health because I want people to know someone in the community is there to help them,” said DeSalvo, noting that YouTube videos that amplified public health messaging during COVID-19 garnered more than 500 billion impressions. Hurricane Ida tore through southern Louisiana on Aug. 30 with winds of up to 150 miles per hour, heavy rain and flash flooding. It knocked out an Entergy transmission system that cut off power to virtually all of New Orleans. The storm set into motion emergency plans that hospitals have honed since Katrina and Isaac. While many hospitals weathered Ida relatively well, New Orleans residents who lost power and water may suffer long-term consequences. “We are significantly more prepared than we were for Hurricane Katrina,” said Greg Feirn, CEO of LCMC Health, which has six hospitals in the New Orleans area. Katrina crippled health system infrastructure and overwhelmed operations. Woman’s Hospital had to improvise a plan to onboard 122 critical newborns via its helipad. Staff called on local churches, shelters and other community partners to watch over relatively healthy infants and mothers when their hospital was full of acute patients, recalled Teri Fontenot, who was at the time CEO of the Baton Rouge hospital. Woman’s has since been written into readiness plans as the designated provider for vulnerable newborns. “We learned that we need to develop and sustain our relationships with our partners at churches and shelters,” Fontenot said. “The Office of Emergency Management also realized it needed to coordinate its response with private entities, not just public.” The federal government has invested $6.8 billion in healthcare disaster preparedness since 9/11, according to HHS’ Office for the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response. Some was earmarked for biohazard preparation. But the disaster plans weren’t well distributed or widely practiced and Louisiana was caught somewhat flat-footed when Katrina hit, DeSalvo said. “Going into Katrina four years later, there hadn’t been the funding or attention on a similar scale for hurricane preparedness,” she said. “That underscored the importance of an all-hazards approach in preparedness, which we do pretty poorly in America.” Ready or not Hospitals should invest in internal and external communication infrastructure, surge capacity, regional coalitions, care continuity plans, staffing contingency scenarios and supply chain management that would apply in all types of disasters, stakeholders suggest. Congress passed the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Reauthorization Act in 2013, which in part authorizes funding for public health and medical preparedness. But progress in all-hazards planning varies by region. Health systems across Colorado, Maryland and New Mexico, among other states, have a regional healthcare information exchange that pools electronic health record data. Providers can track bed availability, personal protective equipment supply levels and staffing trends. “We were able to move together as a system so that one hospital didn’t stand alone,” Marcozzi said. But in some regions, Mays noted, coalitions are “entirely disconnected from regional healthcare information exchanges. We have a long way to go to build out coordination at a local level.” Hospitals have been focused on trimming expenses. The pandemic exposed the limitations of that approach, Mays said, adding, “The short-term spending we incur as a nation to quickly develop surge capacity is far more costly than making sound incremental investments over time.” The intake process, for instance, narrows from seven steps to one or two during a disaster. Typically, systems gather contact information, medical history, verify coverage, collect copays, set up payment plans and consent forms before treatment begins. That process should be streamlined, Marcozzi said. During Katrina, Woman’s Hospital temporarily waived patient data privacy laws; the state and federal government eventually followed suit, Fontenot said. Executives also reduced the steps to grant emergency practice privileges. “Parents were as far away as Oklahoma—it still gives me goosebumps to talk about it. We decided the hell with HIPAA,” Fontenot said, noting that it’s now common practice to relax data privacy and licensure laws during an emergency. “Policies and procedures are important during normal times, but sometimes you have to do what you can to make sure patients are taken care of as safely as possible.” Colorado and Maryland were among the 20 states and the District of Columbia that were ranked in the highest preparedness tier, as calculated by the Trust for America’s Help, which borrowed some data from the National Health Security Preparedness Index. A large grouping of states in the South, including Mississippi, Oklahoma and West Virginia, were among the least prepared and most vulnerable. Those states also have some of the lowest levels of public health emergency preparedness funding in the country.

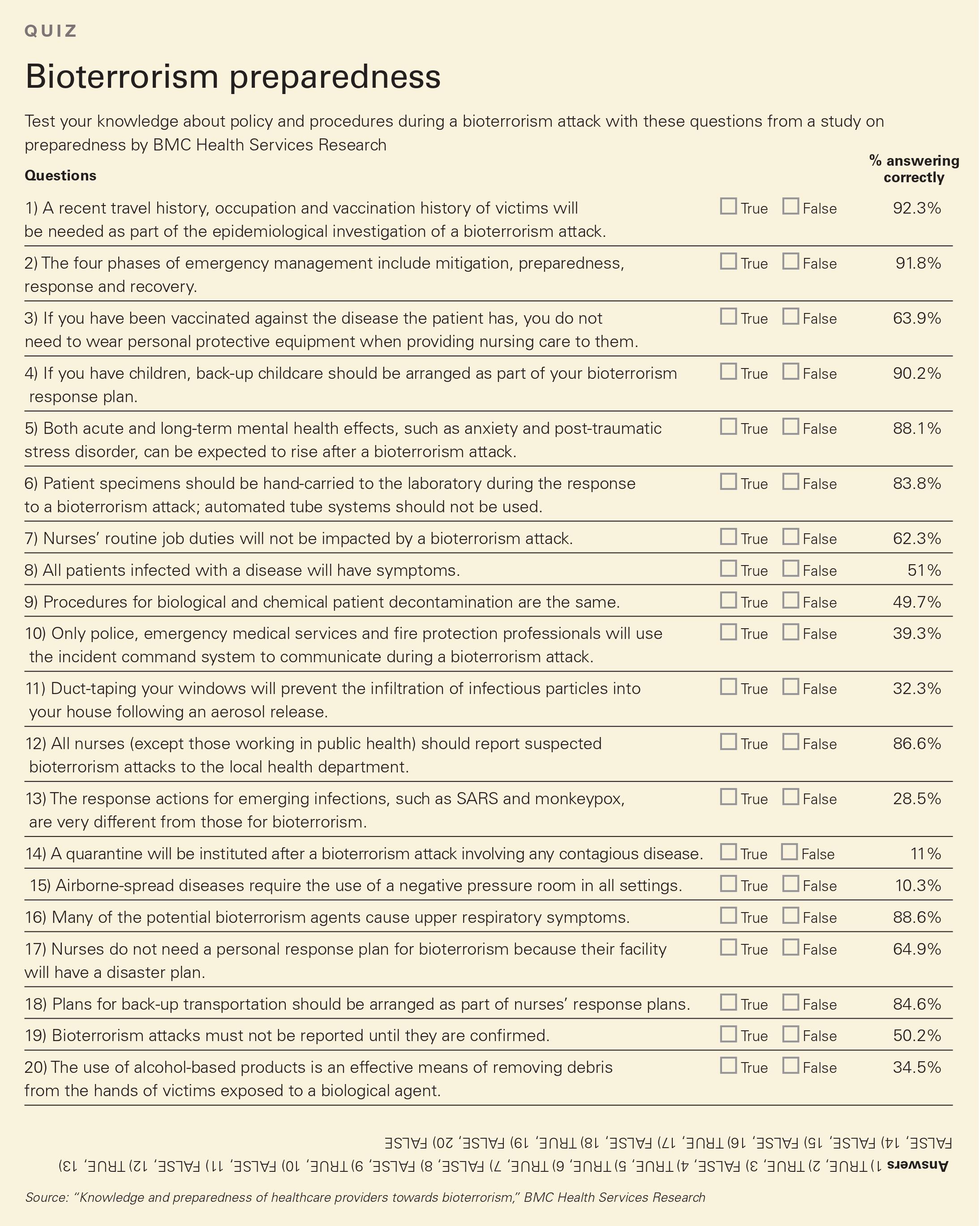

Quiz: Bioterrorism preparedness Bioterrorism preparedness quiz >

States scored better if they were part of healthcare coalitions, participated in licensure compacts, were accredited in public health and emergency management, robustly funded public health efforts, had safer hospitals, had high vaccination rates, and generously offered paid time off, among other measures. More than 100,000 COVID-19 hospitalizations could have been prevented by vaccination in June and July 2021 alone, a recent Kaiser Family Foundation analysis found. That increased spending by more than $2 billion. “We will never ‘grant’ our way to preparedness,” Marcozzi said, noting that hospitals apply for short-term grants after disasters like Hurricane Katrina or the Ebola outbreak. “We have to weave it in with the daily delivery of healthcare.”

Riders on the storm State and federal funding can complicate emergency preparedness. Funding is oftentimes earmarked for specific events. Thus, health systems are hesitant to hire people with that money because they don’t know if it will be sustained, said Nicolette Louissaint, executive director of Healthcare Ready, a healthcare preparedness not-for-profit. “A hospital may need six more people in a department, but how can you hire six long-term employees if you don’t know that the money is going to be there for the long haul?” she said. A massive winter storm swept across Texas in mid-February, prompting calls for infrastructure improvements and better coordinated relief efforts. Water pipes buckled in the unseasonable cold, which disrupted home health and nursing home patients’ care. At Houston Methodist, about 20% of the patients in the system’s emergency departments during the storm were ones who were overdue for dialysis, CEO Dr. Marc Boom said, adding that it was the third major disaster in recent years in which hospitals saw an influx of patients from stand-alone centers. “I don’t think the industry has collaborated enough to prevent endangering patient lives,” Boom told Modern Healthcare in April. More large health systems have built power stations nearby or in some way bolstered their power supply. But coordination, by most marks, is still lagging. The pandemic exposed major gaps in coordinating surge capacity across the healthcare system; building and maintaining preparedness for infectious diseases; readying long-term care facilities and associated training, the Trust for America’s Health report found. “Hospitals are doing better in identifying what high-risk hazards are, but many hospitals still tend to be reactive,” said Markenson, noting that most of the related funding has been event-specific rather than discretionary. “Hospitals are getting ready for what happened five years ago instead of preparing what will happen five years from now.” COVID-19 illustrated the danger of a fragmented and underfunded public health infrastructure. Government public health activities account for less than 2.6% of the nation’s $3.8 trillion annual healthcare bill, according to 2019 CMS data. Federal public health spending has only gone up 15% since 2014. “It is disconcerting to see public health not recognized as an essential element of disaster preparedness infrastructure as it should be,” Markenson said. National investment in public health capabilities is currently about $19 per person. That leaves a $13 per person gap in annual spending to achieve a full foundation of support, DeSalvo said. “For a little more than dollar a month, we could shore up health departments across the country so they’re not they’re just responding to boom-and-bust funding,” she said. It shouldn’t take catastrophes like COVID-19 or 9/11 to bolster public health infrastructure or preparedness. But their warnings should be heeded to honor those we have lost, Marcozzi said. “They show us how we can do better,” he said.

Related Article  Cyberterrorism and the rapidly evolving threat landscape

Cyberterrorism and the rapidly evolving threat landscape  Q&A: ‘Cybersecurity is everyone's job’

Q&A: ‘Cybersecurity is everyone's job’  Q&A: Spurring innovation in emergency response

Q&A: Spurring innovation in emergency response

Source link : https://www.modernhealthcare.com/hospital-systems/gimmie-shelter-rising-tide-emergencies-prompts-need-broader-preparedness