Sergio Roger

Sergio Roger

References to classical Greek and Roman art and architecture seem to be everywhere these days: Sculptor Fabio Viale covers his marble reproductions with tattoo-like designs; Mimmo Jodice’s photographs bring battered antiquities to life in dreamlike images; and planters and candles in the shape of such classical sculptures as Michelangelo’s David and the Venus de Milo are popular among Instagram influencers and TikTokers alike.

In the same vein, Barcelona-based artist Sergio Roger crafts stuffed fabric sculptures that pay tribute to iconic classical artworks. A selection of these sculptures will be on view at the Rossana Orlandi Gallery in Milan during Milan Design Week.

Sergio Roger

Sergio Roger

Roger says his work comes out of how subjective archaeology can be, referring to such misconceptions as the belief—dating back to archaeology’s beginnings in 15th- and 16th-century Europe, when Greek and Roman art was collected by Italian noblemen and Renaissance artists looked to it for inspiration—that classical marble sculptures were pure white. (In fact, it was finally proved in the 1980s that they had been painted.) As Roger notes, such assumptions reflect a cultural bias toward whiteness rather than color. “Archaeology is based on Western, European ideas,” he says. “There are many examples of its interpretations supporting a Western white male narrative.”

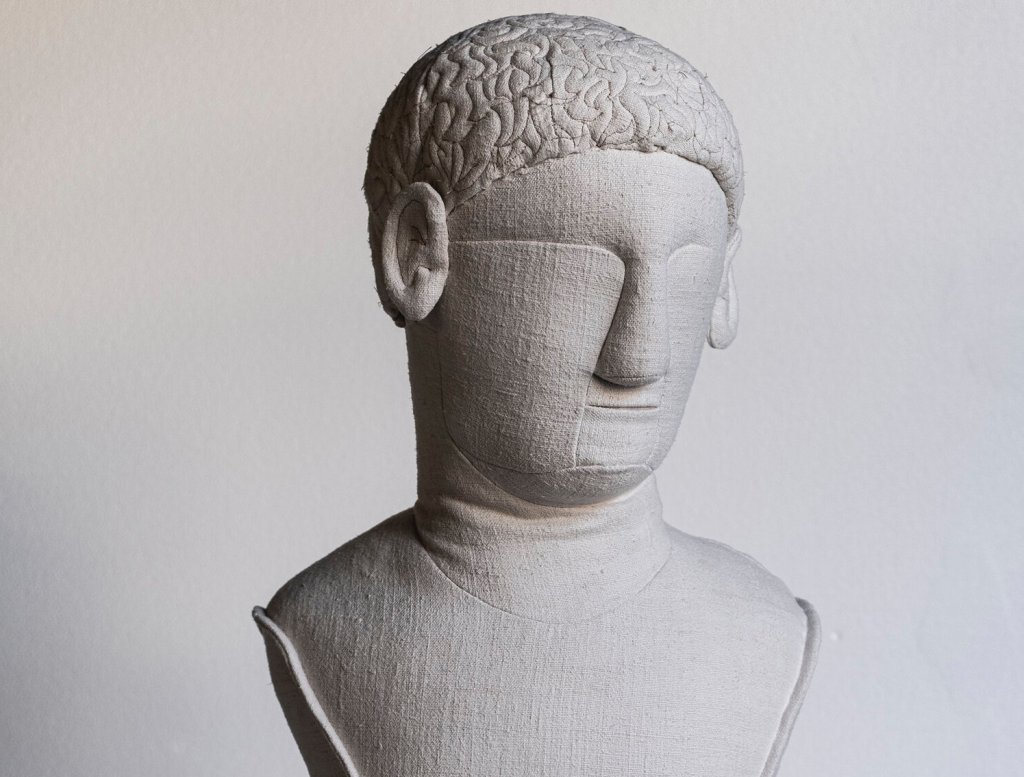

In a quiet subversion of these interpretations, Roger renders his copies of marble and bronze originals in fabric, a medium often associated with women’s work. He generally employs 100-year-old antique linen. “I tried other materials, but this fabric has a history, it has soul,” he says. Furthermore, he adds, textiles are used not only for practical purposes, but also for rituals connected to birth and death. “In almost every culture around the globe, when a child is born it is wrapped in cloth, and when a person dies, they are wrapped in cloth again, this time a shroud.”

Sergio Roger

Sergio Roger

The rough weave of the linen helps Roger create the appearance of stone, and he treats each roll as unique. “I try to make each sculpture from one piece of fabric,” he says. He purchases most of his antique fabric from a local store in Barcelona: “They have an amazing staff, and I also like to support them, especially now [post-Covid] that they’re going through a hard time.” Plus, relying on a brick-and-mortar store as opposed to online sources such as Etsy (which Roger praises for its selection of antique fabrics) allows him to get a sense of the material and what it will look like when quilted or draped.

After creating flat patterns reminiscent of garment patterns, Roger embellishes the linen with stitching. To indicate hair and beards in his busts, he first draws the curls or waves on the linen, then erases the lines once he has worked them in thread. Jupiter (2020), for example, exudes masculinity thanks to his beard, while clean-shaven Augusto (2019), based on images of the first Roman emperor, sports a head of closely cropped curls. Roger then relies on an upholsterer to piece the sculpture together and fill it.

Sergio Roger

Sergio Roger

When a sculpture needs to be clothed, Roger starches pieces of linen, then drapes them over the figure. Starching gives the folds definition, similar to the clarity of folds carved in marble by the Greek and Roman sculptors. His sculpture Cyrene (2021), named after a Thessalian princess who was notable for her bravery, wears an intricately pleated gown fitted at the waist. “I’m very bonded to the fashion world,” says Roger, “because my techniques are related to clothing production.” Ultimately, he credits his assistant, a fashion designer, for how wearable Cyrene’s garb looks even in 2021.

Roger’s sculptures are often displayed on mounts, mimicking the way archaeological finds are displayed in museum settings (and reminding viewers that, just like their marble and bronze counterparts, they’re not meant to be touched.) “Soft sculpture always has this sort of meaning attached to it: ‘We’re going to reproduce the world using fabric; we’ll make it soft and then it’s going to be funny,’” he says. “My work has humor, but I want to walk that very fine line between classical beauty and irony,” he says. “I don’t want to make it too funny or sweet.”

Sergio Roger

Sergio Roger

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-news/artists/sergio-roger-soft-sculpture-1234602783