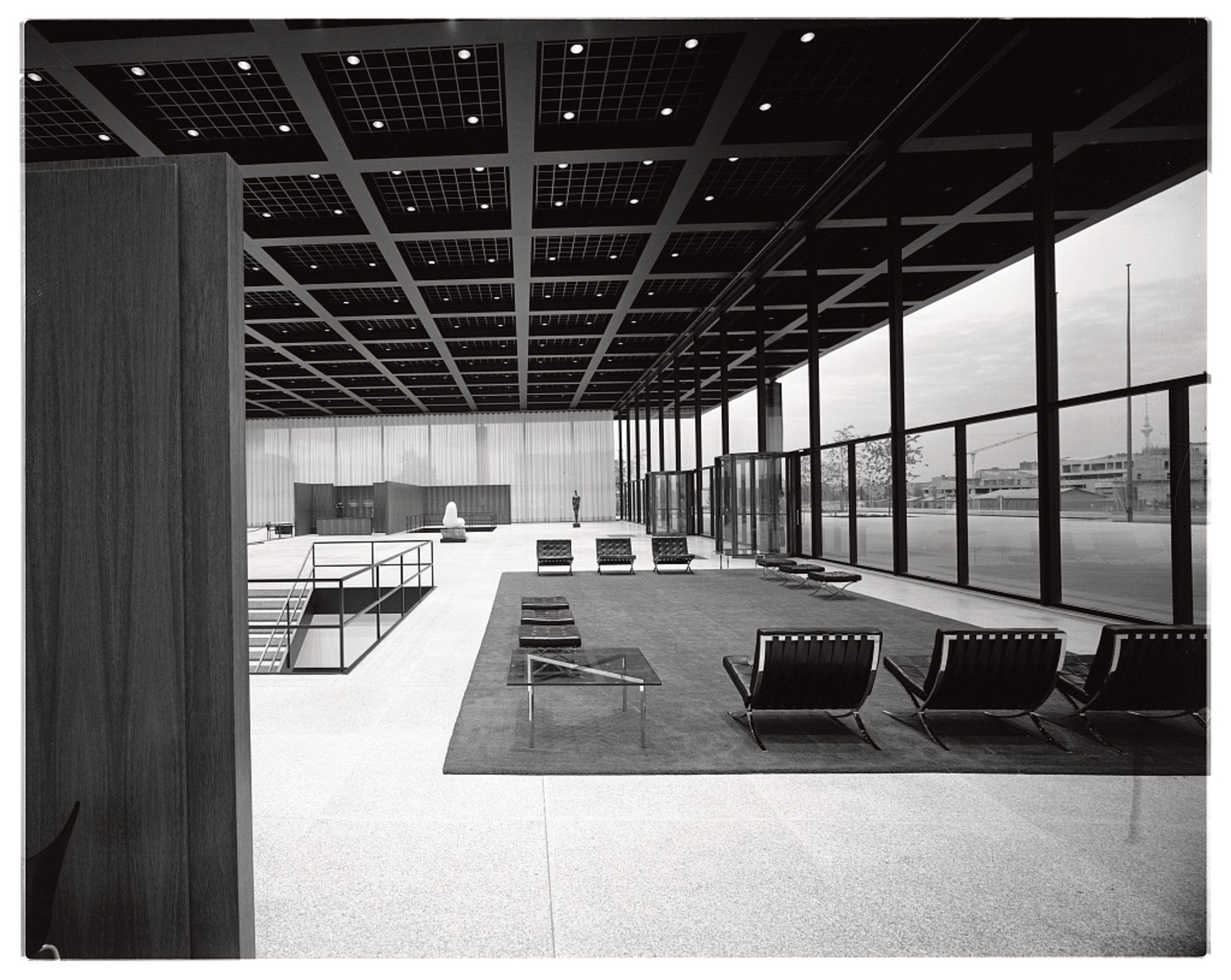

The Neue Nationalgalerie, a masterpiece of 20th-century architecture by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, has undergone “surgery” at the hands of David Chipperfield, a leading architect of the present century. His aim, he says, was to “return this beloved patient seemingly untouched except for it running more smoothly”.

The 1968 steel, concrete and glass landmark, home to Berlin’s vast collection of 20th-century art, reopens to the public on 22 August after an extensive six-year refurbishment costing €140m. To meet the needs of a modern museum, the building required upgrades to its air-conditioning, lighting, security, accessibility, visitor facilities and the behind-the-scenes infrastructure for moving art. Hazardous materials used in the 1960s such as asbestos and artificial mineral fibre had to be removed.

More Mies, please

The client’s brief was “as much Mies as possible”, Chipperfield says. But in a building made of glass, there is, as the British architect puts it, “no place to hide”. Making the comprehensive renovation relatively invisible meant removing around 35,000 building components and then putting them back—as far as possible, in exactly the same place.

“We had to turn over every stone,” says Martin Reichert, the David Chipperfield Architects director in charge of the project. “But we had to treat it with the same care shown by restorers handling a world-famous artwork. After 50 years of use with no refurbishment, there were a great many deficits—this was not just a case of fixing things, it was about making sure it survives the next 30 to 40 years without additional renovation work.”

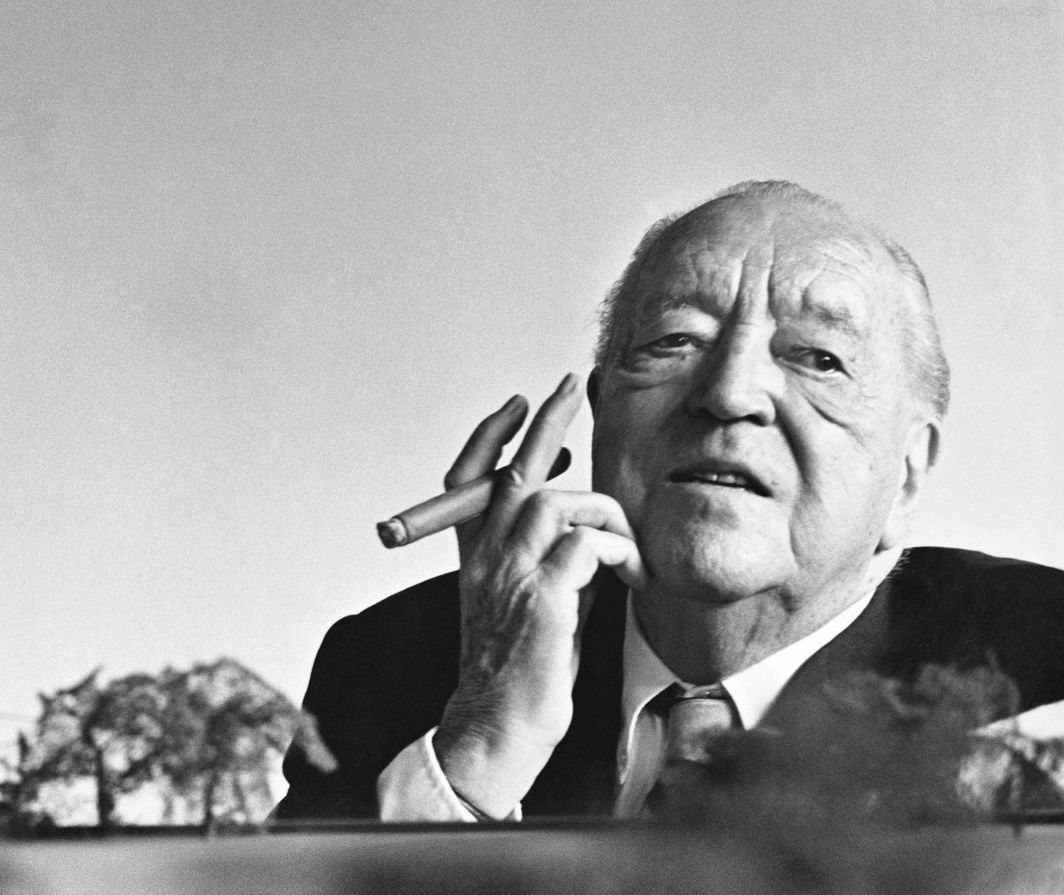

The Neue Nationalgalerie was the only building designed by Mies in Europe after he emigrated to the US in 1937. An icon of Modernism, it also contains elements of classicism, with its temple-like glass hall positioned on a podium. Together with the neighbouring Philharmonie and Staatsbibliothek by Hans Scharoun, it is a candidate for the Unesco World Heritage list.

But in 2015, the museum was in a frightening state. The steel of the façade was corroding in places, causing the glass to break and posing a public safety risk. The building had long suffered from bad condensation, limiting what art could be exhibited in the main hall. It was also difficult to keep the glass hall at a constant temperature because of the amount of daylight that floods in, and because the heating under its stone floor had long ago been taken out of service due to leaks and corrosion.

World-class design, shoddy workmanship

The architects discovered that the original construction work was hardly worthy of a world-class monument. “We think of the Neue Nationalgalerie like a Bugatti or Bentley, a luxury limousine,” Reichert says. “What surprised us, after removing 35,000 building components and looking at the basics of the construction, was how incredibly badly built it was in the basement. It was a typically shoddy post-war job, done with a lack of materials and some slovenly workmanship, and some of the walls were in danger of collapsing.”

A vast amount of archival material dating from the construction at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, helped the architects remain true to Mies’s design. “We had one person working in the archives for almost two years,” Reichert says. The biggest challenge, he adds, was renovating the spectacular façade.

The team replaced the glass with laminated safety glass to eliminate the risk of breakage. They changed the way the façade connects to the roof, using short steel struts to allow it to move. While some condensation is still to be expected, they introduced a draining system. A new ramp has been installed at the south-east staircase of the podium to provide wheelchair access to the main entrance.

The first exhibitions in the newly restored museum open on 22 August. These include an Alexander Calder exhibition in the glass hall, a show featuring the contemporary Berlin-based artist Rosa Barba and a new permanent exhibition, The Art of Society, with 250 Modernist works dating from 1900 to 1945.

Source link : https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/surgical-restoration-of-mies-van-der-rohe-landmark-completed