When a person thinks of vaccines, they often imagine the long needle of a syringe before a slight pinch on their arm, followed by a day of soreness as they recover.

That could soon change if researchers at the University of California, Riverside (UCR), are successful in their attempt to deliver messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine technology via edible plants.

They are hoping that they can grow vegetables that can deliver vaccines with the same technology used to develop the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines.

Plants could be more easily digested than a vaccine shot, and transportation and storage will be easier as well because the vaccine shots need to be kept in very cold temperatures to avoid spoiling.

If successful, these plants could be a boon to lower income nations as they are easier to store and transport than doses of the Covid vaccines.

Researchers at UC Riverside are developing a way to insert mRNA into a plant’s chloroplasts in order to deliver vaccines orally via edible vegetables (file photo)

The mRNA technology used in the Pfizer and Moderna shots – and potentially in the plants, has long existed but was rarely used in medicine until recently.

It works by delivering instructions to the body on how to form spike proteins that fuel Covid infection.

Once a person’s immune system detects the protein, it will fight it, and form immunity to the proteins if they appear again in a person’s body via exposure from the virus.

Companies are now working to apply this technology to other vaccines, including the yearly flu shot.

Juan Pablo Giraldo (pictured) is leading the research, and says he believes it could ‘have a huge impact on people’s lives’

‘Ideally, a single plant would produce enough mRNA to vaccinate a single person,’ said Juan Pablo Giraldo, lead researcher and associate professor in UCR’s Department of Botany and Plant Sciences, in a statement.

‘We are testing this approach with spinach and lettuce and have long-term goals of people growing it in their own gardens.

‘Farmers could also eventually grow entire fields of it.’

Researchers believe that the chloroplasts of the cells can carry genes that are not usually a part of the plant.

This trait means this part of the plant carries a lot of potential.

‘They’re tiny, solar-powered factories that produce sugar and other molecules which allow the plant to grow,’ Giraldo said.

‘They’re also an untapped source for making desirable molecules.’

The team is working to figure out the ideal way to deploy mRNA material into the chloroplasts in a way that will not destroy it.

If successful, the Covid vaccines, and other vaccines that use mRNA technology, will be able to be delivered orally.

It would also allow for a vaccine that can be much more easily transported across long distances.

The current mRNA vaccines need to be stored at temperatures as low at -130f (-90C) and require the use of dry ice.

This can make transporting the vaccines long distances both tough and expensive, and can especially hurt access to the shots in rural or remote areas of the U.S.

Third world countries are hurt as well, as many may not have the resources to transport and store the needed vaccines to distribute them across the nation.

Instead, plants can be grown and easily transported long distances, or even overseas, with ease using technology that already exists to distribute produce around the world.

‘I’m very excited about all of this research,’ Giraldo said.

‘I think it could have a huge impact on peoples’ lives.’

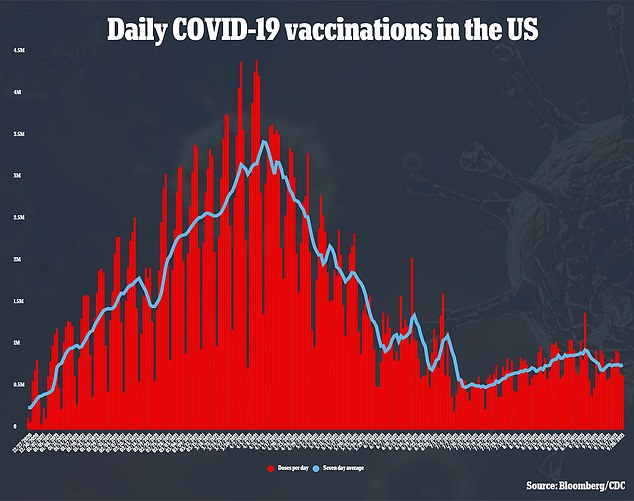

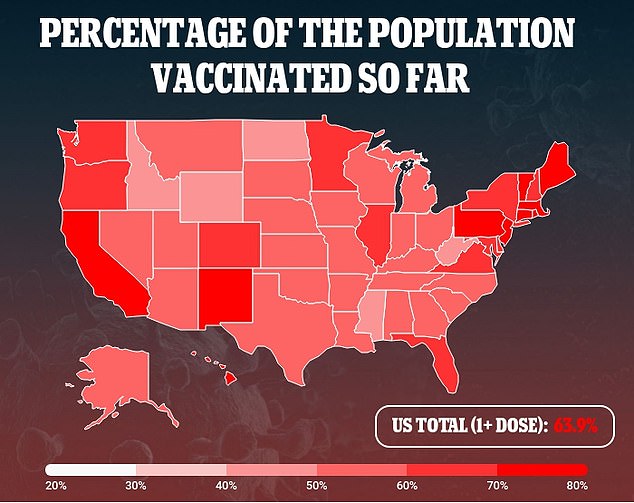

Currently in the U.S., around 64 percent of the total population has received at least one shot of a COVID-19 vaccine and 54 percent is fully vaccinated.

Those figures are much lower worldwide, though, with 44 percent of the global population having received at least one shot and 32 percent being fully vaccinated.

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-10013497/Scientists-working-develop-plants-deliver-mRNA-vaccine-technology.html