A small increase in air pollution from tiny, toxic particles raises dementia risk by 16 percent, a new study finds.

Researchers from the University of Washington used decades’ worth of data from two long-running projects in the Puget Sound region, one on dementia risk factors and one on air pollution.

In addition to increased dementia risk, the researchers found that the same small air pollution increase raised Alzheimer’s risk by 11 percent.

The study suggests that improving air quality could be a key strategy for reducing dementia – especially in vulnerable neighborhoods.

Long-term exposure to air pollution can drive up risk of dementia, a new University of Washington study suggests. Pictured: The Seattle Space Needle during wildfire season in September 2020

It’s well-known among environmental researchers that air pollution can lead to respiratory issues ranging from asthma to lung cancer.

One particularly dangerous type of pollution is called fine particulate matter, or PM2.5 – named because the particles are 2.5 micrometers wide, about 30 times smaller than a human hair.

PM2.5 pollution is tied to car exhaust, construction sites, smokestacks, fires, and other sources.

This pollution has been linked to increased risk of severe COVID-19.

Recent research has also established ties between PM2.5 pollution and dementia, the degradation in memory and thinking ability that often affects seniors.

A new study – published Wednesday in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives – provides evidence for this trend.

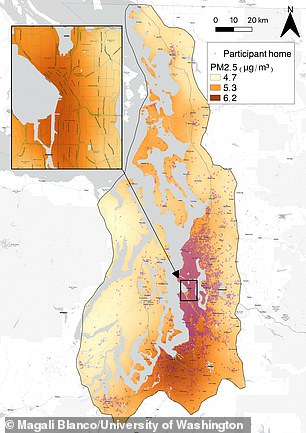

For those patients diagnosed with dementia, the UW researchers investigated their air pollution exposure using past PM2.5 measurements. Seattle’s suburbs tend to have less pollution than the downtown area

University of Washington (UW) researchers investigated decades’ worth of data on dementia development and air pollution in the Seattle, Washington area.

Most studies on dementia risk investigate five years of data or less, making this new research unique in its long time period.

The researchers utilized the Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) Study, a collaborative effort between UW and Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute to identify risk factors for dementia.

ACT researchers followed over 4,000 Seattle seniors for 25 years. The seniors did not have dementia when the study started, but received cognitive check-ups every two years.

Out of those 4,000 patients, over 1,000 were diagnosed with dementia over the course of the study.

For those patients who were diagnosed, the researchers investigated their exposure to air pollution using air quality data – measured regularly in Seattle since 1978.

Using detailed data on where the patients lived, the researchers were able to determine how much PM2.5 pollution they’d been exposed to – and how that compared to the patients who did not develop dementia.

The finding was striking – a tiny increase in long-term pollution exposure drove significant risk of developing dementia.

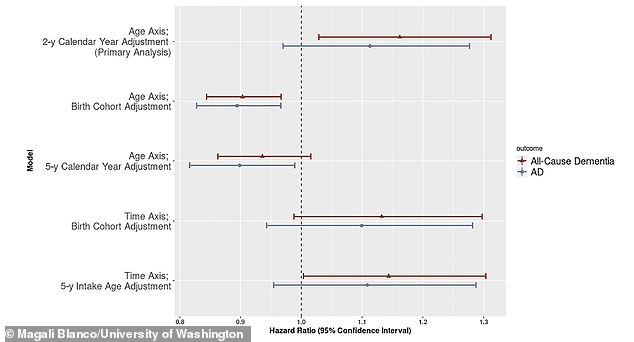

‘We found that an increase of one microgram per cubic meter of exposure corresponded to a 16 percent greater hazard of all-cause dementia,’ said Rachel Shaffer, lead author nd doctoral student in environmental health at UW.

That amount – one microgram per cubic meter – is equivalent to the pollution difference between downtown Seattle and an outlying residential area.

The researchers also found that an increase of one microgram per cubic meter led to a 11 percent higher risk of Alzheimer’s.

These comparisons were made over 10-year spans of exposure to pollution.

‘We know dementia develops over a long period of time. It takes years – even decades – for these pathologies to develop in the brain, and so we needed to look at exposures that covered that extended period,’ Shaffer said.

Shaffer and other researchers on the study expressed thanks to the ACT Study. This study’s long-term data collection made the dementia risk investigation possible.

‘Having reliable address histories let us obtain more precise air pollution estimates for study participants,’ said Lianne Sheppard, senior author on the paper and environmental health professor at UW.

Patients who were exposed to higher air pollution over a 10-year period were more likely to develop dementia or Alzheimer’s

‘These high-quality exposures combined with ACT’s regular participant follow-up and standardized diagnostic procedures contribute to this study’s potential policy impact.’

This research provides key evidence for air pollution’s contribution to dementia and other neurological conditions.

In another recent study, released at the July Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, researchers said that improving air quality is a key dementia prevention strategy.

When neighborhoods are impacted by pollution, the consequences are widespread and long-reaching.

‘Over an entire population, a large number of people are exposed. So, even a small change in relative risk ends up being important on a population scale,’ Shaffer said.

‘There are some things that individuals can do, such as mask-wearing, which is becoming more normalized now because of COVID. But it is not fair to put the burden on individuals alone.

‘These data can support further policy action on the local and national level to control sources of particulate air pollution.’

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-9857965/Small-increases-air-pollution-tiny-toxic-particles-raise-risk-dementia.html