Do you check your breasts regularly for signs of cancer? I didn’t – and I was a breast surgeon who spent a career treating breast cancer. Like most women, I didn’t think breast cancer would happen to me. And then, aged 40, it did.

I saw the lump in my left breast in the mirror one day while getting dressed. I could have sworn it wasn’t there the day before. But it would have been, although for how long I can only guess. Scans showed the tumour was large: about the size of a satsuma.

I had chemo and a mastectomy. And then the cancer came back in the scar tissue where my breast had been, so I had more surgery and more treatment.

I’m now cancer free but it’s changed me, physically and mentally. I had to have an operation to remove my ovaries to ensure drugs I needed to take would work. I’ve also had to give up my job as a surgeon, due to immobility in my arm – a legacy of my treatment.

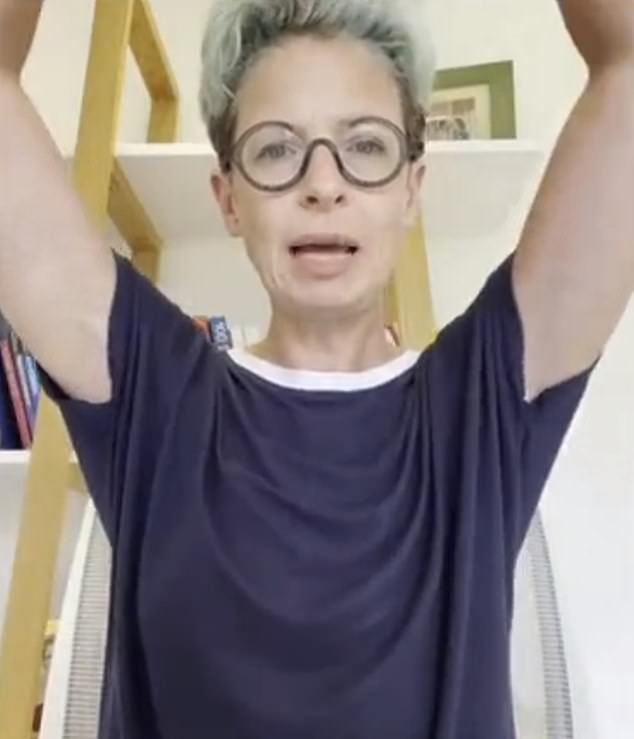

Consultant surgeon Liz O’Riordan, who has twice developed breast cancer, has released a video for women to show how they can check themselves for the disease

Dr O’Riordan, pictured, advises women to raise their arms above their heads before attempting the self examination

And I’ve spent a lot of time wondering whether my life would have been different if I’d discovered that lump sooner – if I’d regularly checked my breasts, as we’re told to.

There’s no point thinking: ‘What if?’ Once I found it, I sought help, just as most women do. But there is always that question, and I now tell people to check their breasts regularly.

The truth is, studies show regular self-checking doesn’t improve breast cancer survival, overall. Some women will develop tumours that we just can’t cure.

But with regular self-examination, you might pick up a cancer at an earlier stage. And this could then mean avoiding a mastectomy and other more aggressive treatment.

Surveys generally show that fewer than half of women check their breasts with any sort of consistency. In my experience, patients do it when they hear a story about a celebrity in the news who has breast cancer. Or they do it before going for a mammogram – although this only applies to women aged between 50 and 70. The risk of getting breast cancer is higher the older you are, and a mammogram can pick up a lump that is too tiny to feel or see.

The message from doctors to women has shifted, subtly, in the past few years from telling everyone to ‘examine’ themselves to just being ‘breast aware’ and ‘knowing what’s normal for you’. Most breast changes are noticed during everyday activities, such as showering or just rolling over in bed.

Dr O’Riordan said it is important to keep checking yourself – even after a mastectomy – as her cancer returned to the scar tissue

But this doesn’t mean it’s not a good thing to know how to examine your own breasts properly – and I’m often asked for the best ways to do this.

In response, I decided to make a series of videos, which I shared on social media, showing exactly how to do it. They’ve already been viewed thousands of times.

I suggest self-examining once a month, in the middle of your period, if you still have them, as this is when the breasts are least likely to be naturally lumpy. Here’s what else you need to know…

First of all, get topless and look

Get topless, in front of the mirror, and look at yourself. This can feel weird – particularly as we’re confronted with endless images of ‘perfect’ symmetrical breasts in the media. Breasts are sisters, not twins, so the saying goes: one is often a full cup size larger than the other and one nipple might be lower.

Don’t judge yourself. Just look. If you have heavy breasts, lift them up so you can see underneath.

Then, with your arms relaxed, turn to one side, and then the other. You’re looking for visible lumps that show underneath the skin. You’re also looking for any puckering of the skin. It might be very subtle.

The reason this happens is that tumours cling on to strands of tissue that go from the chest wall, at the back, through to the skin on the breast. As the cancer grows, it constricts this tissue, and that’s what causes the dimpling you might see. We call this tethering.

In my video, I demonstrated what this looks like using a car washing sponge which I picked up at the local garage.

When I mentioned on social media that I was planning to make the videos, I was inundated with volunteers who said they would let me show how to examine breasts using them as models. But I wanted to keep it all as neutral as possible, and the sponges, while not really the same as breasts, were a fair approximation. They have a certain amount of give – good enough to show how to press down on the breast to feel for lumps (more on that later).

Dr O’Riordan has produced a series of videos on self-examination which have been viewed thousands of times on social media

By folding one corner of the sponge and pressing down, and thereby leaving a mark, I was able to simulate what tethering looks like. It’s a subtle indent, but that’s the point.

Also look at the nipple and whether it has been pulled in – we call this inversion.

Some women have inverted nipples normally. They will probably still stick out when they become erect – when cold or stimulated. But cancer growing under the nipple can pull it inwards, due to tethering, and in these cases it’ll stay inverted whatever happens.

The next thing you do is put your hands above your head. Then put your hands on your hips and push in towards your waist to tense the chest muscles. Doing this can reveal a lump, or tethering, that you might not otherwise see.

There are types of breast cancer than can appear like a red rash, or swollen breasts that have a similar orange-peel look to cellulite. Often, these are infections, but it could be something more serious.

Assume the position… by leaning back

What people don’t realise is that the best way to examine your breasts isn’t standing up – unless you have very small breasts.

The best way to do it is the way a doctor would, and that’s with you lying back. Not totally flat, but reclining – propped up in bed on a few pillows is perfect.

What that does is spread a breast over the chest wall, making it easier to feel.

You need to be able to press the breast tissue against something hard, which you just can’t do when the breast is hanging normally while standing.

And if you have particularly large breasts that like to flop over to the side, you can tilt your body toward the mid-line, which has the same effect.

This makes it much easier to feel if there’s anything there.

Make sure you cover the whole breast

Think of breasts like a teardrop – with the ‘point’ at the top just above your armpit and the rounded bottom fully encompassing the lower part of the breast.

I examine that whole area by feeling in decreasing circles, going around the outside and moving in until I get to the nipple, all the time pressing down and releasing.

Of course, you can choose a different pattern. Some people divide the breast into quadrants, covering the area from the edge inward.

Really, as long as you make sure you feel the whole breast, there are no rules.

When feeling your breasts, the most important thing to know is which part of your hand to use: the under-surface of your fingers, held together – a bit like you do when swimming breaststroke.

Dr O’Riordan advises women to get topless in front of the mirror before starting the examination

This will ensure you’re able to apply firm, even pressure over a large surface area, so any lumps quickly become apparent in contrast to surrounding tissue.

Keep your fingers flat and bend them at the knuckles.

What you’re trying to do is squish your breast tissue on to the ribcage underneath. You push down firmly – the sort of pressure you’d use in a massage. When you get to the nipple, press down quite firmly – so you can feel under them.

Many women have very lumpy breasts naturally. They can feel like a mixture of sweetcorn and jelly, and this is completely normal, and it’s linked to hormonal cycles.

Often, the uppermost part of the breast, near the armpit, is the lumpiest bit. If it does feel lumpy, check the other side. They’ll probably be the same. Other harmless lumps include fibroadenomas, which are made up of glandular and connective tissues, and cysts – these feel round and smooth.

Potentially worrying lumps feel very different: cancerous tumours are often firm and a bit nobbly. But basically any new lump should be checked out, no matter what it feels like.

If there’s a deeper lump, which can’t be seen in the mirror, you’ll notice it as you push down. You should be able to flatten the breast against your chest wall, but if there’s a lump you won’t be able to push as far or as flat.

Don’t forget nodes under the armpits

The final place to feel is underneath your armpits.

This is one place where you have lymph nodes – little glands that are part of the immune system and which are found throughout the body.

Breast cancer, if and when it spreads, goes to the lymph nodes under the armpit first.

You may be able to feel these lymph nodes anyway, particularly if you’re slim. They feel like smooth, pea-sized lumps.

If you’re fighting a cold, or another infection, meaning the immune system is active, they might be easier to feel. But a cancerous lymph node is different – these will be larger, perhaps the size of a small marble or boiled sweet, and hard.

The trick, when checking this area, is to rest the hand of the arm on the side of the armpit you’re feeling, on the opposite shoulder. So if you’re feeling your left armpit, put your left hand on your right shoulder. And relax.

Use your free hand to reach right up and into your armpit, squishing upward and then pulling downward, firmly, to feel for any hard lumps.

Again, use a pulsing, push and release pattern as your move around the area.

Then do the other side.

Keep checking – even after a mastectomy

After I shared my videos on social media, I was inundated with requests from women who’d already had breast cancer, asking me to share methods on how they could keep checking themselves.

And so I put out another clip, showing, on my own mastectomy scar, how to do it.

After overcoming breast cancer, you can still get what’s called a local recurrence – cancer in the area where the breast once was. This is what happened to me. It’s rare, occurring in about one to three per cent of cases, but it does happen because it’s impossible to remove every single cancer cell from under the skin. It’s like trying to remove every bit of pith from an orange – you just can’t do it.

You still need to follow the above rules – look at your breast area and then use your hand to feel.

Dr O’Riordan said she was inundated with requests from women who had previously been treated for breast cancer on the best methods of examining themselves in future

It’s the same teardrop-shaped zone you need to be examining, from below the nipple – or, if it’s no longer there, where it was – up to the collarbone.

Small nodules of cancer cells can form underneath the skin, usually close to the scar.

They can also break through and form little ulcers.

My local recurrence was right on the edge of my scar, below my armpit, and felt like a small, hard nodule – like a bit of gravel.

You can also get a rash all over the surface of the skin in the breast area, which could be a sign of cancer in the skin itself.

In all cases, if you find these things, you need to get checked out by a doctor.

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-10075481/Surgeon-LIZ-ORIORDAN-shows-check-signs-breast-cancer.html