Why is turmeric beneficial for stomach ulcers?

Why is turmeric beneficial for stomach ulcers?

Why is turmeric beneficial for stomach ulcers?

EVERYDAY DETOX DRINKS

The sour truth about kefir: Experts reveal how trendy 'off-milk' drink can destroy your gut health

Being overweight increases your chances of developing 61 life-limiting diseases, finds new study

My husband was secretly copying my apartment papers. I slipped divorce documents to him instead of a power of attorney!

SO HERE’S HOW IT’S GOING TO BE. It’s your celebration—you foot the bill. If you want to eat, cook it yourself

Why Did You Change the Locks? The Dacha Is Ours Too! the sister-in-law suddenly snapped

You need a car, and what does that have to do with me?” — the daughter refused her parents, who once chose her sister over her

“Lyuda, where’s the broth?”—my husband forgot all about food the moment I found a receipt for 128,000 in his pocket

“The feed trough is closed!” — I blocked the cards, and for the first time my forty-year-old husband heard me say: go and earn your own money!

— Decide, my dear, where your son will live when we get married, because he definitely won’t be living with us! I’m not going to support someone else’s child!

“My husband handed the holiday savings to his mother—so I served him an empty table.”

‘What, are you offended? I was just joking!’ my husband smirked. But I wasn’t laughing anymore

I was kicked out of my childhood home at 18. I came back at 50 to buy out the entire street—along with their pathetic secrets

Vitya, your wife didn’t give me the money you promised! Deal with her yourself as soon as possible—otherwise I’ll tell Mom and Dad everything, and you’ll have to talk to Dad about it

"every stone of this mountain reminds me that the love we have built is the only sanctuary we will ever truly need," david whispered to sarah as they watched the sunrise paint the peaks in uncorrupted gold

"our house is not just walls and a roof, it is the sacred place where every laugh we share builds a future that belongs only to us," david said softly to his wife and children as they sat together by the fireplace

"i noticed you were never in bed at two in the morning, and i have spent every hour since then wondering who has taken my place in your heart," marcus said with a voice heavy with grief as he stood in the doorway of her lit office

"I saw the glow of your phone at two in the morning, and i cannot help but wonder who is more important than our sleep," elara said with a voice trembling with hidden heartbreak as she confronted him in the dimly lit hallway

Why is turmeric beneficial for stomach ulcers?

EVERYDAY DETOX DRINKS

The sour truth about kefir: Experts reveal how trendy 'off-milk' drink can destroy your gut health

Being overweight increases your chances of developing 61 life-limiting diseases, finds new study

My husband was secretly copying my apartment papers. I slipped divorce documents to him instead of a power of attorney!

SO HERE’S HOW IT’S GOING TO BE. It’s your celebration—you foot the bill. If you want to eat, cook it yourself

Why Did You Change the Locks? The Dacha Is Ours Too! the sister-in-law suddenly snapped

Why You Should Never Tie a Ribbon on Your Luggage, According to a Baggage Handler

How my grandmother cared for her varicose ve.ins with only three simple kitchen staples

Heart fai.lure dea.ths are increasing, doctors say - These 4 habits raise the risk

Regularly drinking coconut water can amaze you with its incredible health benefits

Doctors reveal that eating boiled eggs in the morning causes....

What to know about sweet potatoes: 8 facts that matter

Clove Water: The Quiet Strength of a Kitchen Staple

Stop Storing Ginger in the Fridge! Here’s How to Keep It Fresh for Up to 6 Months

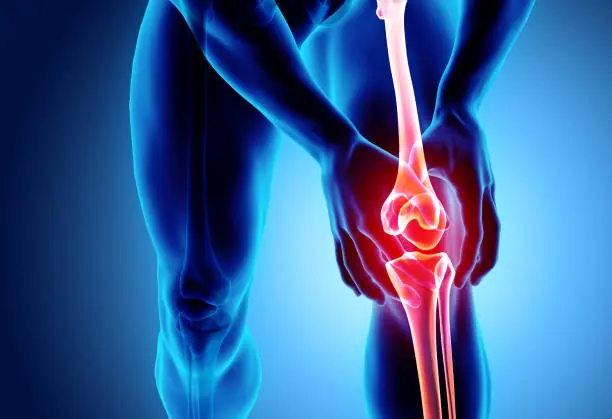

Health Warning: Overconsuming These 6 Foods May Lead to Calcium Loss and Fragile Bones

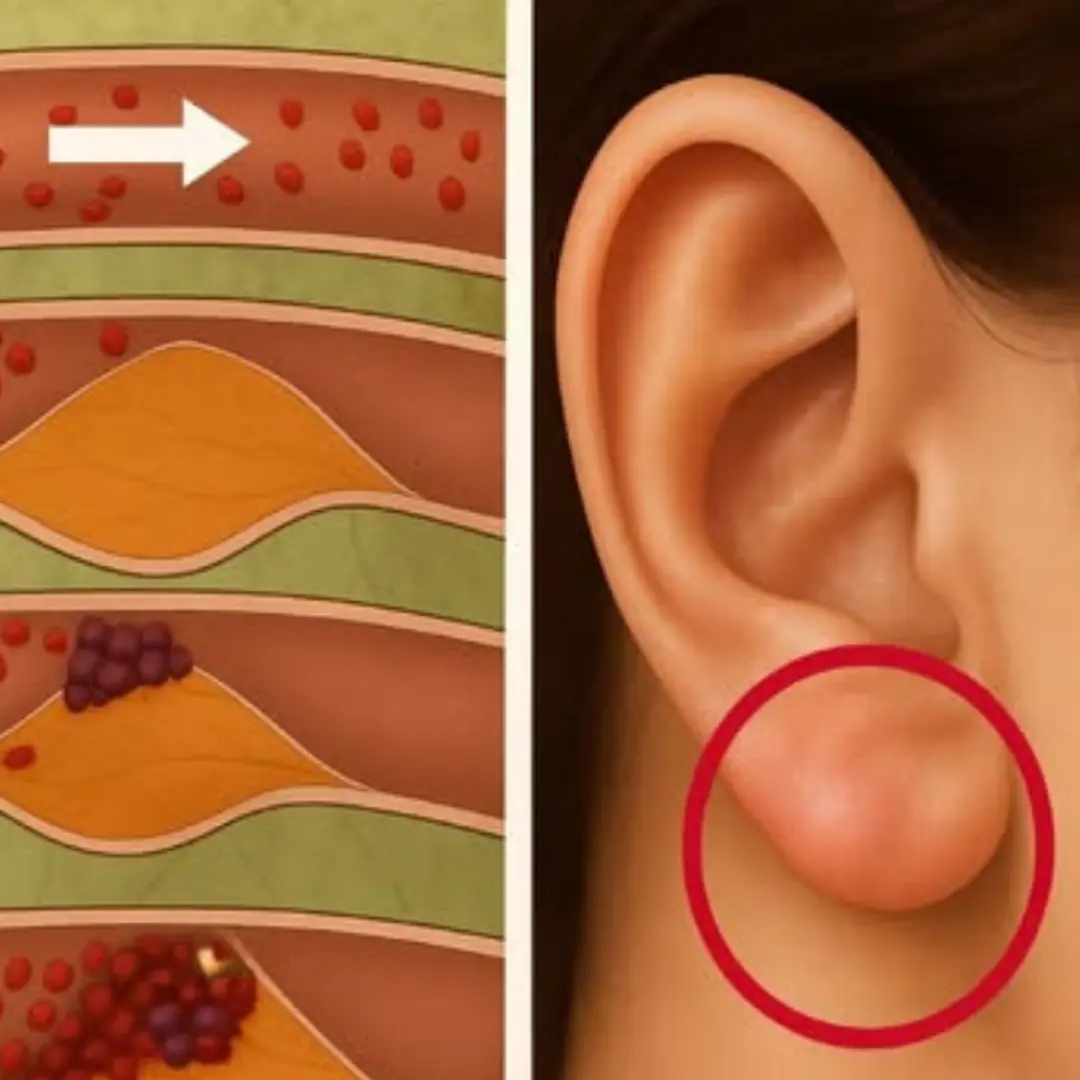

Warning Signs Your Arteries Need Cleansing and The Foods That Do It Best

Put salted lemons next to your bed and wake up to refreshing, family-wide benefits