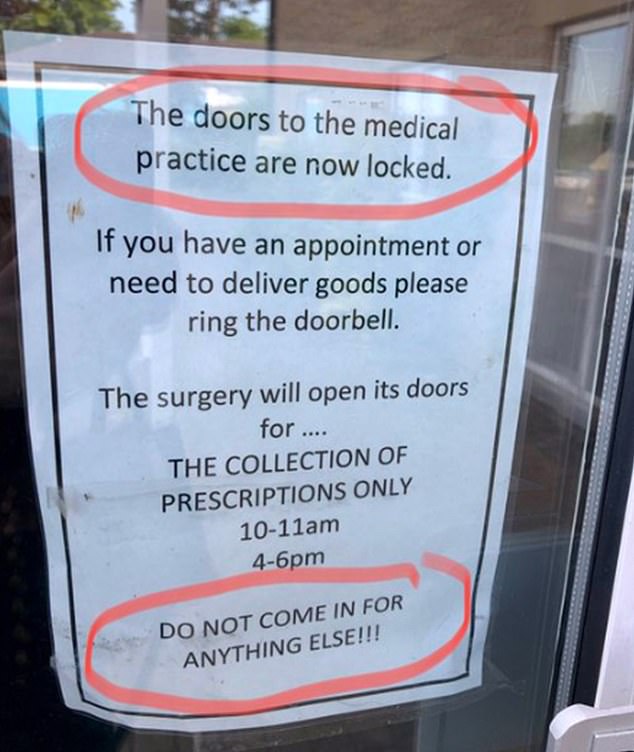

Last month, I shared a picture with my Twitter followers of a sign taped to the door of my local GP surgery.

‘The doors to the medical practice are now locked,’ the note read. ‘If you have an appointment or need to deliver goods please ring the doorbell. The surgery will open its doors for THE COLLECTION OF PRESCRIPTIONS ONLY. DO NOT COME IN FOR ANYTHING ELSE!!!’

It explained why I’ve been fobbed off for more than a year, and forced to listen to an automated message listing coronavirus symptoms, over and over again, every time I called to try to make an appointment.

Along with the picture, I shared my disdain for the rude tone of the note. Not exactly indicative of a warm and welcoming NHS, I wrote. Within minutes I had more than 600 replies, most of them from disgruntled, ignored patients. One told of his wife, who has cancer, going three months without seeing a medic when prior to Covid she was seen fortnightly. Another said they couldn’t even get through to a receptionist despite making 30 attempts.

The Mail on Sunday first raised the alarm about this back in November, and then again in April. The reports followed an influx of letters from more than 1,000 readers, telling of serious conditions missed by GPs because they’d been denied face-to-face appointments.

Along with the picture (above), I shared my disdain for the rude tone of the note. Not exactly indicative of a warm and welcoming NHS, I wrote. Within minutes I had more than 600 replies, most of them from disgruntled, ignored patients

But in May, NHS England published new guidance to GP practices, urging them to offer all patients a face-to-face appointment if they asked for one. ‘All practice receptions should be open to patients,’ it stated.

Clearly my local practice – and the hundreds referred to in my Twitter thread – didn’t get the memo. So I spoke to a GP contact of mine to find out what the situation was right now.

‘It’s much the same,’ Dr Mike Smith, a GP partner working in Hertfordshire, told me. ‘The NHS emailed practice managers back-tracking on the advice, telling us it was perfectly fine to do telephone appointments only if the GP thinks it’s the most appropriate option.

‘So you get a lot of variation between clinics. From what I hear, very few GP surgeries are letting patients book face-to-face appointments in the same way they did.’

There’s no doubt that GPs have been hugely pressured – a survey of nearly 50,000 junior doctors revealed a third of them have suffered burnout over the past year.

The doctors’ union, the British Medical Association, say GPs have gone ‘above and beyond’ in response to the pandemic, and are threatening strike action should the Government refuse to give them a pay rise. But with thousands of fobbed-off patients, it’s hard not to assume that some GPs have been sitting around at home with their feet up.

In an effort to get to the bottom of it, I took up the kind offer of one GP, Dr Dean Eggitt, who contacted me via Twitter to invite me to shadow him for the day at his practice on the outskirts of Doncaster.

Could he convince me that GPs really are trying their best?

7.30am: Dr Eggitt arrives at The Oakwood Surgery. His first task is to analyse the hundreds of X-rays, blood tests and other results that have landed on his desk via local hospitals. He describes the daily pile as ‘insurmountable’. He adds: ‘All routine tests were paused during lockdown, but NHS England has just restarted them. Plus, the population is sicker than ever before, having put off going to the doctor for a year or developed sedentary-related diseases.

‘We’ve suddenly got thousands more results to go through.’

8am: Phone lines open. Within seconds, they’re jammed. There are three receptionists manning the phones, which will ring solidly for the next three hours.

For the past six years, Oakwood Surgery has followed NHS England protocol designed to free up the time of hard-pressed GPs, which makes trained receptionists responsible for deciding which patients are worthy of a GP appointment. Since Covid, the criteria to be granted one have got even stricter.

On the front line: Dr Dean Eggitt outside The Oakwood Surgery on the outskirts of Doncaster

Dr Eggitt’s attitude to this is similar to mine: it isn’t working. ‘The Government has seized the opportunity to rejig the system using telephone and online appointments which, it says, is to ease pressure on doctors,’ he says. ‘But, to be honest, it isn’t right for anyone.

‘Patients hate it. Receptionists feel out of their depth and doctors are terribly worried that patients will fall through the net. I’ve no doubt there are a number of patients who will end up in the wrong hands, with the wrong outcome.’

So why do it?

‘The truth is we don’t have enough clinicians to deal with the number of patients who need to be seen. We’ll try what the Government suggest, but only because we don’t have another solution.’

8.15am: The first batch of patients come through to Dr Eggitt’s phone via the receptionists. One patient illustrates the absurdity of the system perfectly.

A 65-year-old man complains of serious lower back pain. Dr Eggitt asks a question which surprises me: ‘Have you been passing urine OK?’ It turns out that back pain in a particular type of male patient is often a red flag for prostate cancer.

‘The first place prostate cancer spreads to is the back, and if there’s problems urinating it’s alarm bells,’ Dr Eggitt explains.

The man has been going to the toilet more frequently – Dr Eggitt’s hunch may well be right. But receptionists very nearly sent him straight to a physiotherapist.

Thankfully, the man’s wife insisted he speak to the doctor.

Dr Eggitt says: ‘A receptionist might think, what man in his 60s doesn’t have back pain? It’s normal. A doctor would think: this could be prostate cancer.’

GP FACTS

One in three GPs is now considering early retirement, according to a survey by the British Medical Association.

Advertisement

8.30am: A surprising number of phone calls are about the menopause. Recently a documentary aired on Channel 4 called Sex, Myths And The Menopause, presented by Davina McCall, featuring women who were denied hormone replacement therapy by their GP, and instead fobbed off with antidepressants.

But Dr Eggitt’s response is far from dismissive.

He explains that deciding whether to give HRT involves a complicated risks vs benefits analysis, due to the small increased chance of cancer in some groups of women.

He then invites them in to see a female doctor the following day, for a proper discussion.

The phone chats last for about 20 minutes each. He’s frustrated at the system – yet again, it has wasted both his and the patients’ time.

‘A face-to-face conversation is part of the treatment,’ he says. ‘It’s about making women feel heard and that their problem isn’t in their head. So I’ve had to spend two appointments dealing with a problem I could have sorted with just one.’

10.20am: Not every patient wants a face-to-face appointment. There’s a call from a local convent – staff are worried about an elderly sister who is unsteady on her feet and increasingly confused. Dr Eggitt wants her to come to the surgery. She doesn’t want to. He suggests a home visit instead.

He tells me: ‘There is a hidden wave of patients who won’t come in because they’re scared I’ll refer them to the hospital, where they think they’ll catch Covid.’

Another patient, a 35-year-old teacher who has been suffering bouts of severe diarrhoea for three months, didn’t want to bother Dr Eggitt for a ‘tummy upset’. He worries she may have bowel cancer.

‘You have to see a patient more than once over a period of time to tell if diarrhoea is a sign of something serious,’ he says. ‘Another symptom might crop up and you can link the two together. That’s what we’re missing.’

The teacher also has agonising stomach cramps and disabling exhaustion. He makes an urgent referral to cancer specialists.

11am: I’m about to grab my coat for the home visit when Dr Eggitt’s phone pings to remind him to join a Zoom meeting. The local Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) – the watchdogs in charge of his practice – want to discuss the state of community healthcare.

Since March last year, new diagnoses of diabetes are up 56 per cent, thanks to extra pounds gained by many during lockdown, and more young people than ever need mental health support.

‘I can’t remember the last time a young patient got accepted for treatment by children and adolescent mental health services,’ he says. ‘There’s only space for the most seriously ill.’

Since March last year, new diagnoses of diabetes are up 56 per cent, thanks to extra pounds gained by many during lockdown (file photo)

This situation creates another steady flow of phone calls for Dr Eggitt – those with depression, anxiety and eating disorders, until a specialist is finally free to help.

11.30am: We jump into his car and head for the convent.

Before entering, he puts on PPE (an apron, gloves and surgical mask) and is briefed by a young matron. We step into the sister’s room to find her sitting on the side of her bed, hands clasped together. She smiles but it is soon clear she does not know what day of the week it is, nor the year.

Dr Eggitt suspects dementia, but doesn’t know for sure. ‘Dementia is often diagnosed when family members or GPs notice a gradual decline over time,’ he says. If patients are in residential homes, it can be tougher.

He recommends a series of tests to rule out other conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease or a stroke.

12.30pm: Back to his desk. One call is from a woman who has a dark mole on her shoulder which has changed shape. She hasn’t done anything about it for a year because she ‘didn’t want to bother anyone’.

Dr Eggitt asks her to come into the surgery that afternoon – he is obviously worried about her. ‘You can’t help the fact she waited,’ he says, ‘but if she was here right now I could take a picture of the mole and send it to the dermatologist to know what we were dealing with.’

GP FACTS

Salaried GPs in the UK earn a minimum of roughly £58,000, according to the careers advisory firm Prospects.

Advertisement

1.30pm: No time for a lunch break – Dr Eggitt must see the 20 patients who have been scheduled in for face-to-face appointments.

Among them are a labourer with tennis elbow, a cheerful South African with aggressive lung cancer and an elderly man who is losing weight and complains of feeling very weak. Dr Eggitt notes down his skin colour: ‘If a patient looks tanned and then gets slightly more tanned the next time I see them, that’s a change in skin colour, which is another red flag.’

Jaundice – yellowing of the skin – can be a sign of liver problems and even pancreatic cancer. And is another thing you wouldn’t notice on the telephone.

2.20pm: Drama erupts as the clinic’s pharmacist bursts into Dr Eggitt’s office asking about a young man who has lost a lot of weight.

Listening to his symptoms – sudden weight loss, extreme thirst and going to the toilet a lot – Dr Eggitt knows it is type 1 diabetes. Sufferers cannot produce insulin, the hormone that is crucial for converting the sugars from food into energy. If untreated for too long, it is fatal.

Dr Eggitt orders a test to measure the young man’s blood sugar level. Ten minutes later the results show it is critically high. He turns to me and with a deep breath says: ‘We have definitely saved a life today.’

3pm: The woman with the skin mole comes in. Dr Eggitt discovers the lymph nodes in her armpit are swollen – often a sign of cancer that has spread. Thank goodness he invited her in, I think. He arranges an urgent referral to a specialist.

4pm: A patient with chronic leukaemia who also has heart failure and kidney disease and is taking more than ten daily medications comes in for a drug review, and happens to mention he’s going on holiday the following week.

Dr Eggitt’s ears prick up. ‘The drop in oxygen supply on a plane could prove fatal for people with your combination of conditions,’ he says. ‘Without access to supplementary oxygen, it’s very likely you won’t survive the trip.’

The man looks miserable, but says he will consider something closer to home.

When the patient leaves, Dr Eggitt tells me drug reviews aren’t exactly in his job description. ‘It requires detailed, expert knowledge of these conditions, which is almost beyond my medical capabilities,’ he says.

But since Covid, input from hospital staff is ‘sparse to infrequent’. ‘They’re also trying to deal with a backlog of appointments, so we have to step in,’ he adds.

There’s no doubt that GPs have been hugely pressured – a survey of nearly 50,000 junior doctors revealed a third of them have suffered burnout over the past year, writes Isabel Oakeshott (pictured outside The Oakwood Surgery)

6pm: When I point out to Dr Eggitt that he hasn’t eaten properly all day, he reaches for a packet of biscuits on his desk and smiles wryly. Lunch is obviously a luxury.

Despite the Covid-related disruption to his working day, we’ve seen no actual Covid. Until…

The final patient of the day is a labourer who thinks he has sinusitis. It quickly becomes obvious he has Covid-19. He works in a meat-processing plant, where cold air encourages the virus to spread. It does not seem to have occurred to him that he might have the virus.

Dr Eggitt and I stare at each other in disbelief. For the first time, I think maybe it’s too early to scrap all telephone appointments.

6.30pm: Dr Eggitt sighs at his computer screen, and looks helpless. There’s a list of hundreds of urgent cases he didn’t manage to get to today – not to mention the many more who failed to get through on the phones.

He’s planning to take test reports home to catch up with patient notes later that evening. He doesn’t blame patients for being angry. ‘It’s not a surprise when people are redialling 30, 40 or 50 times a day, and still get nowhere,’ he says.

Clearly, doctors are not work-shy. Dr Eggitt is desperate to see patients in person. But the system is in need of a reboot. The solution? To me, it’s obvious: let patients see their doctors properly if they want to. But you’d need far more GPs to do this. Politicians can’t instantly conjure them up, but they can do more to hold on to the GPs we already have.

After my day on the job, I’d say the proposed pay rise of three per cent is the very minimum. Plus more for the system, in general.

Throwing fancy technological solutions at clinics might lighten the load temporarily but not without compromising care. General practice needs to be torn apart and put back together properly, not patched over with a flimsy plaster.

As Dr Eggitt says: ‘Covid is the extra straw on the camel’s back – but the camel was already dead.’

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-9847323/ISABEL-OAKESHOTT-day-frazzled-GP-proof-seeing-patients-face-face-saves-lives.html