Why Many People Put Lemon with Salt in Their Room – A Little-Known Trick

The Surprising Benefits of Placing Lemon with Salt in Your Room

The Surprising Benefits of Placing Lemon with Salt in Your Room

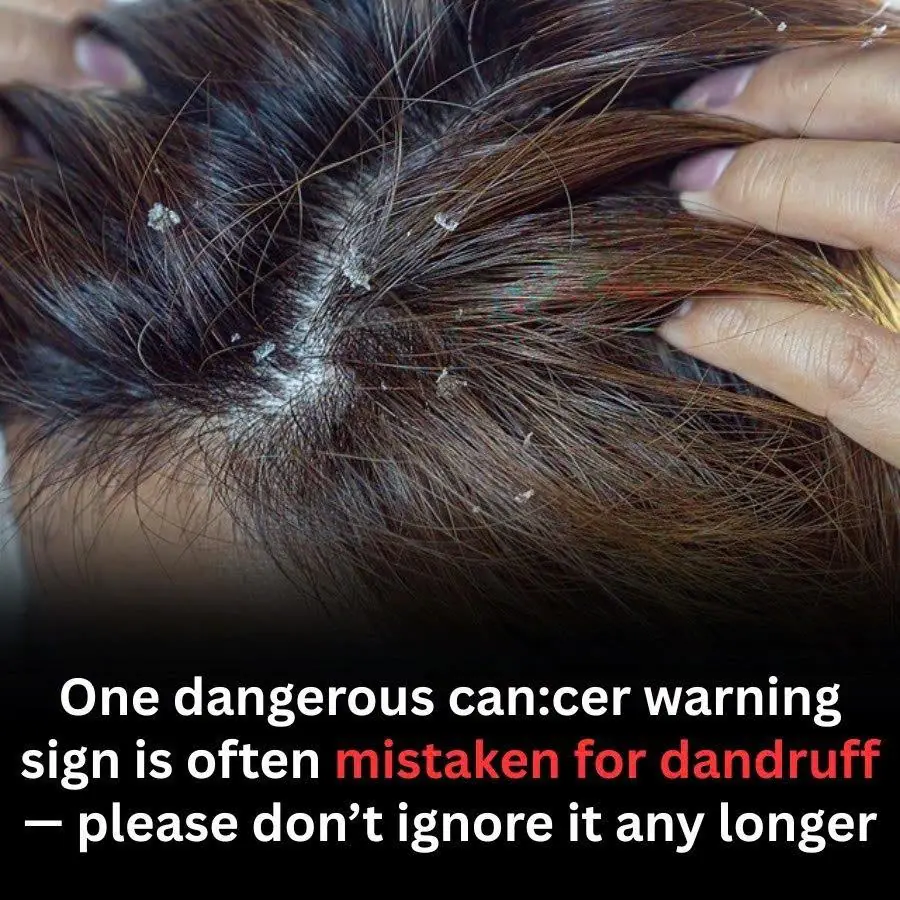

A Cancer Warning Sign Often Mistaken for Dandruff — Why Doctors Say You Should Not Ignore It

Should You Leave the Bathroom Door Open After Using It?

Don’t Ignore These 20 Early Warning Signs That Your Body Could Be Fighting Can:cer

8 Early Warning Signs of Kidney Problems That Often Go Unnoticed

Drooling While Sleeping Often: What It Could Mean for Your Health

Many serious illnesses do not begin with dramatic pain or sudden collapse.

Pain is one of the body’s most important warning systems. In many cases, it is caused by benign issues such as muscle strain, poor posture, or temporary inflammation.

Doctors Issue Warning: These 4 Morning Symptoms May Signal Lung Cancer Is Advancing

As we grow older, protecting brain health becomes one of the most important parts of maintaining a good quality of life.

These 5 everyday foods could quietly destroy your kidneys

Warm Water Each Morning Can Be a “Healing Tonic”

Neuropathy, or nerve damage, is a frequent complication that arises in individuals with diabetes.

5 Plants That Might Bring Snakes Into Your Garden – Many People Still Grow Number 1

8 Early Signs of Cervical Cancer That Often Go Unnoticed

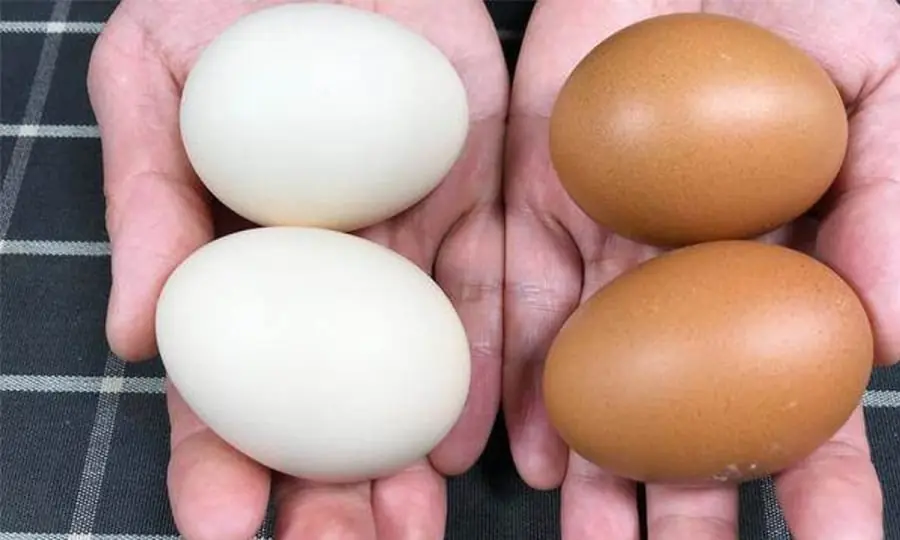

When Buying Eggs, Should You Pick Red or White Ones?

Millions Do This When They Wake Up at Night — Doctors Say Stop

Fatty Liver: 7+ Silent Symptoms You Must Pay Attention To

Many People Miss These Early Diabetes Symptoms