Associated Press  Bloomberg

Bloomberg

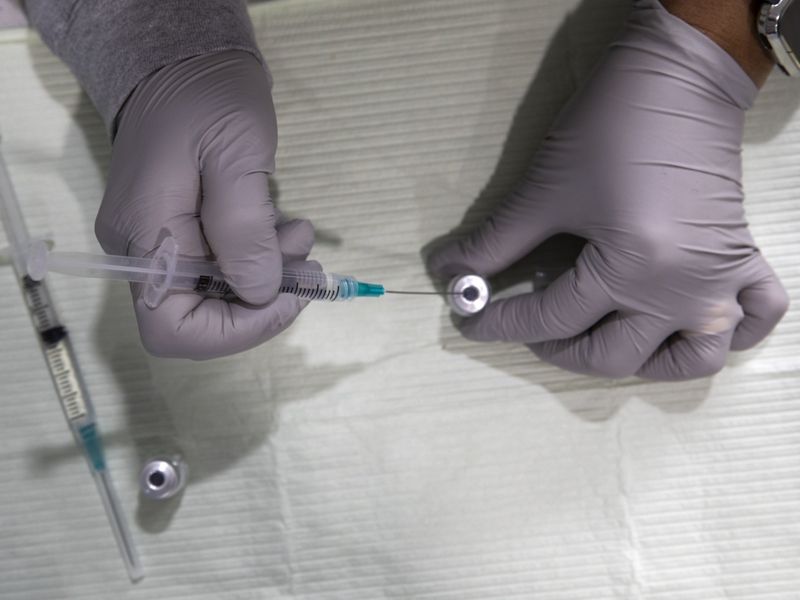

An influential panel of advisers to the Centers for the Disease Control and Prevention grappled Wednesday with the question of which Americans should get COVID-19 booster shots, with some members wondering if the decision should be put off for a month in hopes of more evidence. The doubts and uncertainties suggested yet again that the matter of whether to dispense extra doses to shore up Americans’ protection against the coronavirus is more complicated scientifically than the Biden administration may have realized when it outlined plans a month ago for an across-the-board rollout of boosters. Much of the discussion at the meeting of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices focused on the possibility of a scaled-back booster program targeted to older people or perhaps healthcare workers. But even then, some of the experts said that the data on whether boosters are actually needed, precisely who should get them and when was not clear-cut. “What would be the downside” of simply waiting a month in hopes of more information? asked Dr. Sarah Long of Drexel University. The two-day meeting had been scheduled to resume on Thursday, but it was not immediately clear whether that would happen. The meeting came days after a different advisory group — this one serving the Food and Drug Administration — overwhelmingly rejected a sweeping White House plan to dispense third shots to nearly everyone. Instead, that panel endorsed booster doses of the Pfizer vaccine only for senior citizens and those at high risk from the virus. While the COVID-19 vaccines continue to offer strong protection against severe illness, hospitalization and death, immunity against milder infection seems to be dropping months after vaccination. “I want to highlight that in September of 2021 in the United States, deaths from COVID-19 are largely vaccine-preventable with the primary series of any of the three vaccines available,” said CDC advisor panel member Dr. Matthew Daley, a researcher at Kaiser Permanente Colorado. And the public must understand that no matter how good a COVID-19 vaccine, when it comes to milder infections, “it is unlikely that we will prevent everything,” said Dr. Helen Keipp Talbot of Vanderbilt University. Several panelists said another challenge is the public confusion that could result if they recommend a booster only for certain recipients of the Pfizer vaccine, leaving people vaccinated with Moderna or Johnson & Johnson shots wondering what to do. Booster shots of the Pfizer vaccine were the question before the panel. Moderna more recently applied for authorization of a third dose, and a major U.S. study on whether mixing-and-matching booster doses is safe and effective isn’t finished Many experts are torn about the need for boosters because they see the COVID-19 vaccines working as expected. It is normal for virus-blocking antibodies to be highest right after vaccination and then wane over the following months. “We don’t care if antibodies wane. You care what is the minimum” needed for protection, Long said. No one yet knows the antibody level threshold below which someone’s risk for infection suddenly jumps. Even then, the body has backup defenses. Antibody production and even those backup defenses don’t form as robustly in older people. But it’s impossible to pinpoint the age at which that becomes a problem, CDC microbiologist Natalie Thornburg told the committee. Ultimately the committee must decide who is considered at high enough risk for an extra dose. CDC officials presented data from several U.S. studies, saying there is growing evidence of a decline in the effectiveness of both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines in preventing new COVID-19 infections in some groups, most notably people 65 and older and healthcare workers who got shots early in the vaccination campaign. There’s also a hint that at age 75, there may be some decline in protection against hospitalization. But the CDC said there is little information on waning immunity in younger people with chronic medical problems. Some panelists also wondered about boosters for healthcare workers who can’t come to work if they get even a mild infection. “We don’t have enough healthcare workers to take care of the unvaccinated. They just keep coming,” Talbot said. Another question was how many months after the second shot the booster should be given. Scientists have talked about six months or eight months. As for booster safety, serious side effects are exceedingly rare with the first two doses. And Pfizer pointed to 2.8 million booster doses given in Israel, mostly to people 60 and older, with fewer reports of annoying side effects like pain or fever with the third dose than with the earlier shots. There was one report of a rare risk, heart inflammation, that is sometimes seen in younger men. In the U.S., more than 24,000 people who have volunteered for a CDC vaccine safety tracking system have reported getting an extra dose, and likewise have reported no red flags.

Source link : https://www.modernhealthcare.com/supply-chain/cdc-panel-grapples-who-needs-covid-19-booster-shot