Rates of depression in Britain are starting to fall after shooting up during the Covid pandemic, official data shows.

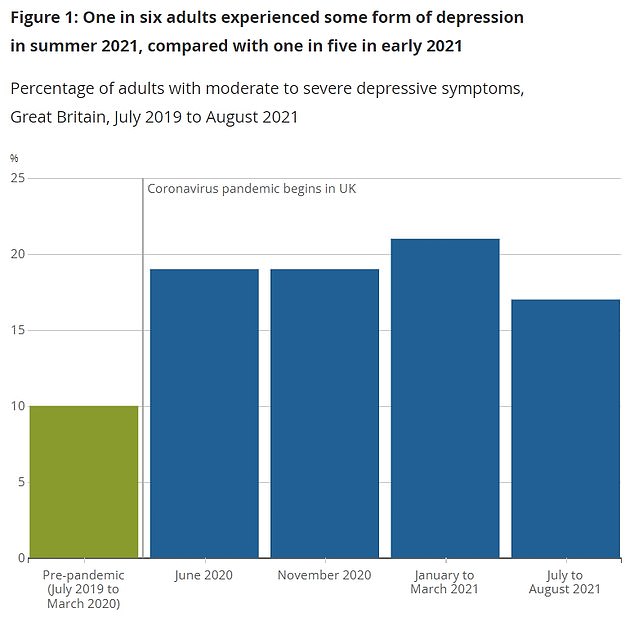

The Office for National Statistics estimated that 10 per cent of adults in the UK were depressed before the virus first struck.

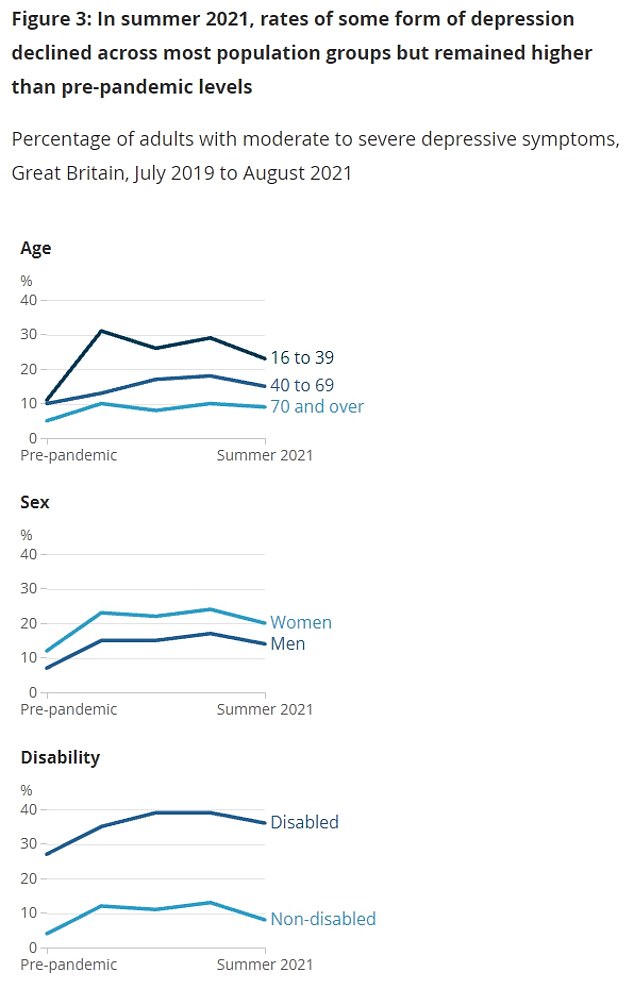

This more than doubled to a record 21 per cent last winter after two brutal waves of the epidemic and three lockdowns, with women and young people worst affected.

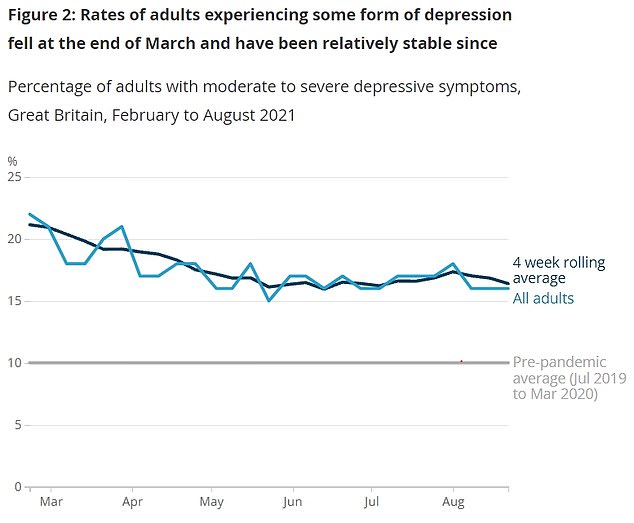

The ONS estimates that the proportion dropped to 17 per cent last month, based on its rolling survey of nearly 14,000 people across the country.

Lockdowns, social isolation, job cuts and fears about the pandemic have all been linked to higher rates of depression in other studies.

Most Covid curbs and social restrictions have been dropped around the UK since the summer despite some variation between countries. It is compulsory in Scotland and Wales, for example, to wear a face mask in most indoor public spaces.

The furlough scheme came to an end this week and there are concerns this could lead to a wave of job losses.

Rates of depression in Britain are falling after shooting up during the Covid pandemic, official data shows. The Office for National Statistics estimated that 10 per cent of adults in the UK were depressed before the virus first struck

This rose to a record 21 per cent last winter after two brutal waves of the epidemic and three lockdowns, with women and young people worst affected. The ONS estimates that the proportion has come down to 17 per cent last month, based on its rolling survey of nearly 14,000 people across the country

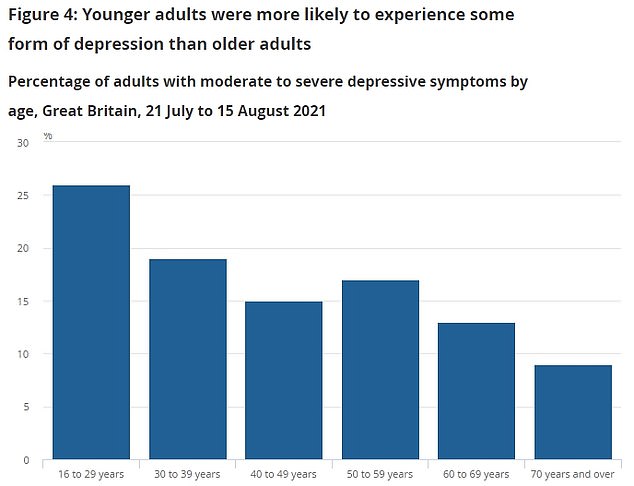

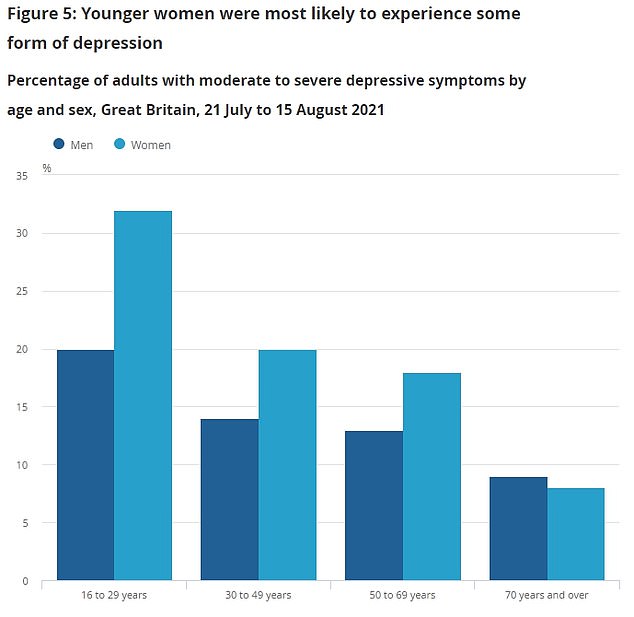

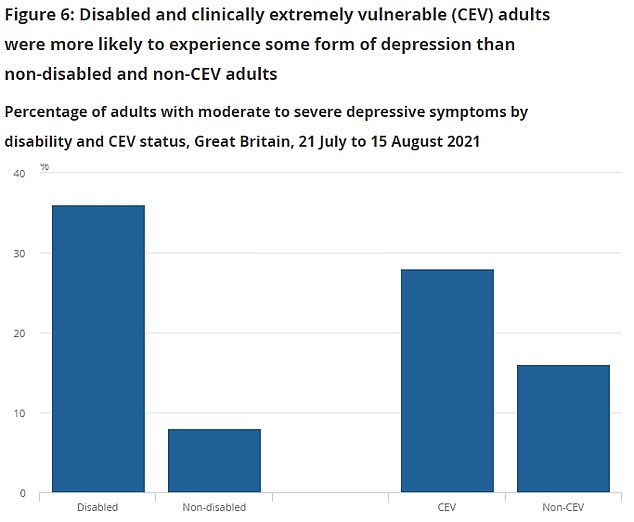

Women and young people have consistently been the most likely to admit to being depressed. Disabled (36 per cent) and clinically vulnerable people (28 per cent) were also more likely to experience depression than the fit (8 per cent) and healthy (16 per cent)

The ONS’ report found between July 21 and August 15, one in six adults experienced some form of depression (17 per cent).

One in three females aged 16 to 29 said they were suffering from the condition (32 per cent), compared to 20 per cent of males in the same age group.

Tim Vizard, head of the ONS policy evidence and analysis team, said: ‘Today’s data shows that while there has been a fall in the proportion of adults experiencing some form of depression, levels are still above where they were pre-pandemic.

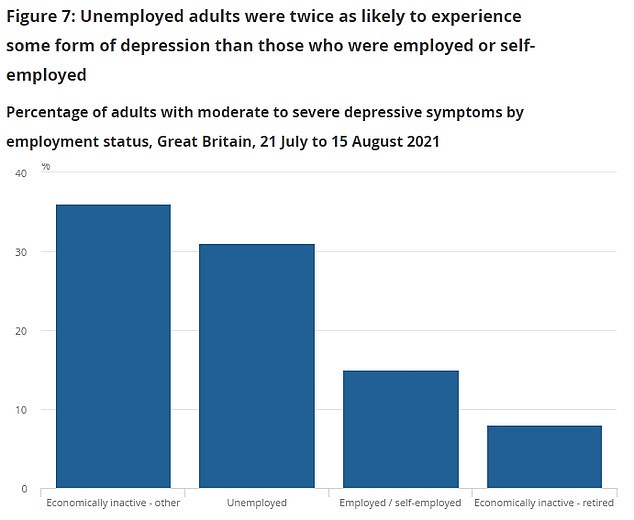

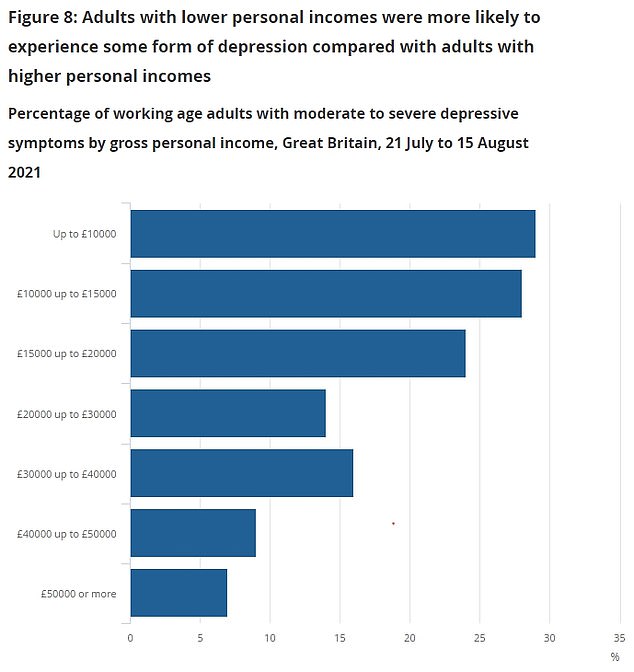

‘Younger adults, women and disabled people are more likely to experience some form of depression, along with the unemployed and those unable to afford an unexpected expense.’

To estimate the prevalence of depression in the country participants were asked whether they had taken little pleasure doing things and how often they had felt down, hopeless or depressed in the previous two weeks.

Three-quarters of older teen girls ‘may have eating disorder’ after pandemic hits youngsters’ mental health, NHS study says

More than half of older teenagers may be suffering with an eating disorder, a major NHS study has warned.

The amount of children aged 11 to 17 who suffer problems with eating has almost doubled since 2017, figures from the Mental Health of Children and Young People survey, published by the NHS, showed.

The research also found that one in six children in England now have a mental health problem, which has gone up up from one in nine in 2017.

Nearly one in six older teens were suspected of having an eating disorder, which could include anorexia and bulimia in extreme cases.

Meanwhile some 76 per cent of girls aged 17 to 19 were found to have a ‘possible eating problem’ – up from 61 per cent four years ago.

In boys the same age, the figure was 41 per cent.

Professor Tamsin Ford, a child and adolescent psychiatrist at the University of Cambridge, stressed the number of children reporting difficulties with eating was not the same as those diagnosed with eating disorders, and said it was not yet possible to know the reason for the sharp increases.

Advertisement

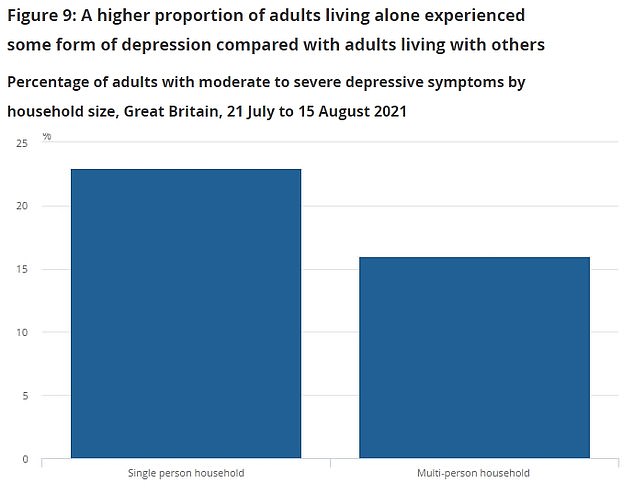

Results also showed a higher proportion of adults living alone (23 per cent) experienced depression this summer than those living in multi-person households (16 per cent).

Disabled (36 per cent) and clinically vulnerable people (28 per cent) were more likely to experience depression than the fit (8 per cent) and healthy (16 per cent).

Unemployed adults were twice as likely to experience some form of depression (31 per cent), compared to those who were employed or self-employed (11 per cent).

It comes after a major NHS study warned yesterday that children’s mental health has been worsening in recent years and it may have been exacerbated by the pandemic.

The research found that one in six children in England now have a mental health problem, which has gone up up from one in nine in 2017.

Professor Dame Til Wykes, a clinical psychologist at King’s College London, said the rises ‘may have been accelerated by the pandemic’.

She told MailOnline: ‘But it seems part of a longer term progression and recognition of mental health difficulties in the young.’

England has faced three Covid lockdowns since March 2020, forcing the entire country to stay home and pushing schools and universities online.

There were a myriad of other restrictions in place which placed limits on social groups.

Two years’ worth of GCSE and A level students saw their examinations disrupted, sparking distress for many over securing a space at university.

Professor Wykes said she would have been more surprised if children’s mental health hadn’t taken a hit during the pandemic.

She added: ‘Most people have suffered ‘a little’ and it would be surprising to all of us if they had not said that.

‘We wanted to mix with friends, see work colleagues in person and generally have a better and more informal approach to work…’

‘What we should do right now is to pay attention to those who were most seriously affected, about one in six children and young people.

‘Those who had a probable mental health disorder in this research were more likely to miss school.

‘We already know that mental health problems reduce educational achievement and career prospects so we need to identify those who need help now to prevent these future adverse consequences.’

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-10049005/Depression-rates-dropping-theyre-nearly-twice-high-pre-Covid.html