A plant considered an invasive species in Britain, the Japanese knotweed, has been used by scientists to create a healthier form of red meat.

The fast-growing plant, feared by homeowners for its ability to invade gardens and buildings, contains a chemical called resveratrol, which could take the place of the currently-used nitrite preservatives in meats like bacon, sausages and ham.

Nitrites in processed meats result in the production of carcinogenic chemical compounds called nitrosamines, and have previously been linked to a higher risk of colorectal cancers.

Researchers found that red meats supplemented with the knotweed extract reduced the creation of compounds in the body that are linked to cancer.

Nitrites in processed meats result in the production of carcinogenic nitrosamines – and therefore increase cancer risk for those who regularly consume traditional bacon and ham

The fast-growing plant feared by homeowners: Everything you need to know about Japanese knotweed

Japanese Knotweed is a species of plant that has bamboo-like stems and small white flowers. Native to Japan, the plant is considered an invasive species.

The plant, scientific name Fallopia japonica, was brought to Britain by the Victorians as an ornamental garden plant and to line railway tracks to stabilise the soil.

It has no natural enemies in the UK, whereas in Asia it is controlled by fungus and insects.

In the US it is scheduled as an invasive weed in 12 states, and can be found in a further 29.

It is incredibly durable and fast-growing, and can seriously damage buildings and construction sites if left unchecked. The notorious plant strangles other plants and can kill entire gardens.

Capable of growing eight inches in one day it deprives other plants of their key nutrients and water.

Advertisement

The research is taking place as part of the PHYTOME (phytochemicals to reduce nitrite in meat products) project, which has received backing from the EU.

‘The ongoing worries about highly processed red meat have often focused on the role of nitrite, and its links with cancer,’ said study author Gunter Kuhnle, professor of nutrition and food science at the University of Reading.

‘The PHYTOME project tackled the issue by creating processed red meat products that replace additives with plant-based alternatives.

‘Our latest findings show that using natural additives in processed red meat reduces the creation of compounds in the body that are linked to cancer.’

For their study, the researchers tested a mixture of plants and fruits, including rosemary, green tea, and resveratrol, an extract taken from Japanese knotweed.

These natural extracts were added to meat mince or curing brines to develop PHYTOME versions of cooked and dry cured red meats.

While resveratrol is found in a range of foods, such as red wine, fruits and nuts, the researchers opted for the Japanese knotweed as a source of because it didn’t change the texture and flavour of the meat product, nor did it have any risk as a potential allergen.

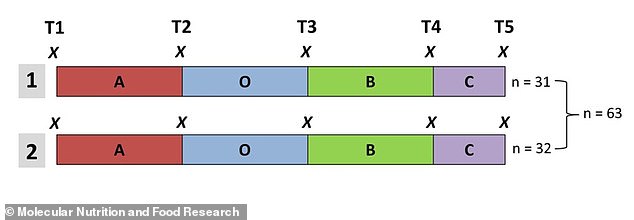

In all, 63 healthy subjects consumed 300g of meat per day for two weeks in the following order – conventional processed red meat, white meat, and PHYTOME processed red meat products (with the added natural extracts).

At the end of each dietary period, the researchers looked for tell-tale signs of nitrite in participants’ saliva, faeces, and urine.

The researchers found that nitrites in participants’ bodily samples were significantly lower from both cooked and dry cured red meats containing the added plant extracts.

Japanese knotweed (pictured) is considered an invasive species in the UK and plagues people’s gardens

Red meat and cancer

Red meat – such as beef, lamb and pork – is a good source of protein, vitamins and minerals, and can form part of a balanced diet.

But eating a lot of red and processed meat increases your risk of bowel (colorectal) cancer.

That’s why it’s recommended that people who eat more than 90g (cooked weight) of red and processed meat a day cut down to 70g or less.

This could help reduce your risk of bowel cancer.

Other healthier lifestyle choices, such as maintaining a healthy weight, keeping active and not smoking can also reduce your risk.

Source: NHS

Advertisement

Nitrite levels of those fed the special meats were like those who were fed on minimally processed white meat.

Surprisingly, the natural additives seemed to even have some protective effects when the red meat still contained nitrite.

‘This suggests that natural additives could be used to reduce some of the potentially harmful effects of nitrite, even in foods where it is not possible to take out nitrite preservatives altogether,’ said Professor Kuhnle.

Despite the findings, Dr Duane Mellor, a registered dietitian at Aston Medical School, Aston University, who was not involved in the study warned that sausages and bacon ‘are not quite health foods yet’.

‘Although this may help resolve one of the health challenges from consuming bacon and sausages, their salt and fat intake needs to be considered as these may not be desirable health wise, so perhaps sausages and bacon are not quite health foods yet,’ he said.

‘It is good that traditional products such as herbs are being rediscovered as ways of preserving meat and that these ways might be healthier than brining type methods for making sausages and bacon.’

Dr Mellor also pointed out that resveratrol is found in grapes and red wine, as well as Japanese knotweed.

Many of us love a good bacon sandwich, but experts have warned that merely consuming a daily couple of rashers of bacon or one hotdog – again, around 50g – can raise the risk of bowel cancer by around a fifth

‘So, it is perhaps less important that this compound is obtained from Japanese knotweed, it is more that a range of compounds which have antioxidant properties obtained from vegetables and fruit are able to help preserve meat products and through storage and digestion lead to less carcinogenic compounds being produced,’ he said.

It’s worth noting that as part of the study, 31 of the participants were placed in group 1 and had their PHYTOME meat of with a normal nitrite content, while the remaining 32 in group 2 had PHYTOME meat with a reduced nitrite content.

Researchers found there was virtually no difference between the groups.

‘This means that the extracts used reduce the formation of nitrosamines quite reliably,’ Professor Kuhnle told MailOnline.

A major consideration for the team was how the nitrate content in drinking water can significantly affect the formation of nitrite, which is produced in the body, as found in previous research.

Image from the paper illustrates the study method. A = processed red meat products, O = control period with only white meat; B = processed red meat products with added natural extracts; C = drinking water nitrate at acceptable daily intake; X = bodily samples taken. Study subjects were split into two groups, each with different amounts of nitrite in the specially-created plant extract meat sample (B). Group 1 had the normal nitrite content; group 2 had the reduced nitrite content

The team controlled for this by controlling water content during the trial and participants were tested with both low and high nitrate-containing water across separate testing periods.

‘What was also interesting was the finding that these extracts also reduced reliably the formation of nitrosamines when we increased the nitrate content in drinking water to the maximum allowed concentration,’ said Professor Kuhnle.

‘So the compounds in the extracts can reduce overall exposure to nitrosamines fairly well.’

The study has been published in the journal Molecular Nutrition and Food Research.

WHY ARE THERE NITRITES IN BRITISH FOOD?

Scientists have known about the health risk of nitrites in cured meats for more than half a century.

But consumers have not been sufficiently alert to the danger, or have preferred to do nothing about it.

In 1956, British scientists Peter Magee and John Barnes tested the safety of nitrite-type chemicals – because they were also being used by dry-cleaners.

Their findings showed nitrites cause liver cancer in rats. By the 1970s, other researchers revealed that repeated nitrite doses – at the levels consumed by people who regularly eat bacon – caused numerous tumours in animals.

By the mid-1990s, nitrites were also being associated with human cancers such as brain tumours.

A bigger threat to the key ingredient of the Great British Fry-Up came in 2012 when researchers reported in the British Journal of Cancer that a daily bacon sandwich or a single sausage, equivalent to an average serving of 50 grams, was associated with a 19 per cent increase in risk of pancreatic cancer.

And then, in 2015, World Health Organisation (WHO) scientists classified bacon and other processed meats as a Group One carcinogen.

This top-level danger classification meant the world’s leading scientists were convinced nitrites cause cancer – and bowel cancer in particular.

The WHO warned that eating bacon and other cured meats may cause an extra 34,000 cancer deaths a year worldwide.

Experts warned that merely consuming a daily couple of rashers of bacon or one hotdog – again, around 50g – would raise the risk of bowel cancer by around a fifth.

The medical doctor and science journalist, Michael Mosley, has put it more starkly. He believes that every bacon sandwich you eat knocks half an hour off your life.

The WHO’s findings were enough to cause a panic. In the ensuing fortnight, British supermarkets reported bacon sales had plummeted by £3 million.

However, the ‘killer bacon’ crisis promptly abated. After all, it’s very hard to ponder a theoretical danger of potential ill-health when faced with a bubbling rasher of salty, savoury pleasure.

Advertisement

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-10012883/Scientists-use-Japanese-knotweed-make-nitrate-free-bacon.html