Just six in 10 children have received both MMR vaccines in parts of London, according to official figures that lay bare the huge geographical divide in uptake.

NHS data analysed by MailOnline show rates among five-year-olds are as high as 96.4 per cent in County Durham, which leads the way in England. But they dip to just 59.8 per cent in Camden.

Statistics show the proportion of children getting their first MMR jab by the time they turn two has fallen over the past eight years, after hitting a record high in 2013.

Experts have blamed the rise of anti-vaxx sentiments, fuelled by bogus claims that the vaccine – which protects against measles, mumps and rubella – can cause autism and bowel disease.

One virologist warned uptake has to be 90 per cent to thwart measles, one of the most infectious viruses known to exist. More than half of the local authorities in England (57 per cent) fall below the threshold.

It has led to pockets of England having much lower uptake of the jab, mirroring trends seen in the Covid vaccine roll-out, which has lagged behind in BAME communities.

The MMR vaccine is given in two doses, the first when a child is one-year-old and the second when they are three years and four months old.

Measles, mumps and rubella can spread easily between unvaccinated people. The infections can lead to serious problems, such as meningitis, hearing loss and problems during pregnancy.

Two doses of the jab protects around 99 per cent of people from getting measles and rubella, while around 88 per cent of people are protected against mumps.

The graph shows the proportion of children in England who received their first dose of the MMR vaccines by their second birthday from 1988 to 2021. Figures began dropping dramatically in 1998 when a now-discredited study wrongly linked the jabs with autism. Rates began climbing again in 2004 after hitting an uptake level of just 79.9 per cent in 2003/2004. But they began to fall again in 2014. In 2020, the uptake rose to 90.6 per cent, but in the last year it has dropped to 90.3 per cent

The 10 areas with lowest MMR vaccine uptake among five-year-olds are all in London, which overall has a rate of 75.1 per cent. Just 59.8 per cent of youngsters in Camden have received the jab, while 63.7 have in nearby borough Hackney and 64.1 per cent have in Westminster

Areas with the highest uptake are Country Durham (96.4 per cent), West Berkshire (94.1 per cent), Sunderland (95.4 per cent) and Dorset (95.3 per cent). Four of the areas with the highest uptake are in the North East, which is the region with the most children protected against the measles, mumps and rubella (92.5 per cent)

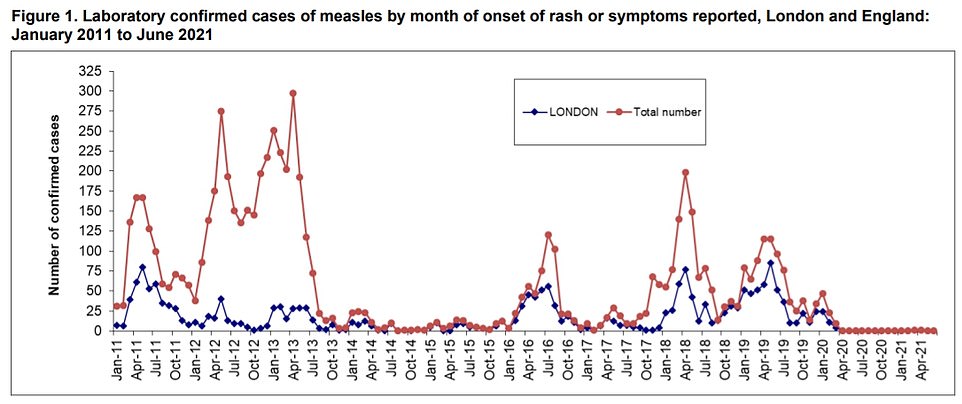

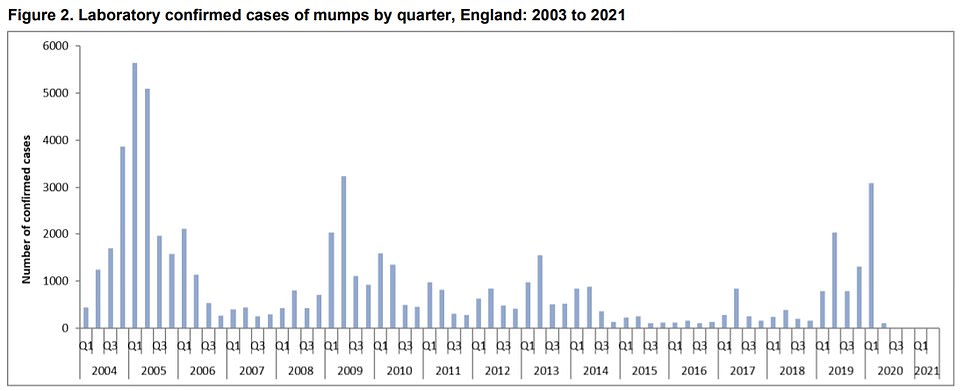

Between April and June this year, Public Health England confirmed there was one measles case and two mumps cases. There have been no confirmed cases of rubella reported in the UK since 2019

Official data released yesterday showed just 59.8 per cent of children in Camden had received both doses of the MMR vaccine by their fifth birthday by March.

All of the 10 areas with the worst uptake are in London, with Hackney (63.7 per cent), Westminster (64.1 per cent), Kensington and Chelsea (65.9 per cent) and Haringey (67.7 per cent) rounding out the top five.

Meanwhile, boroughs with the highest uptake are Country Durham (96.4 per cent), West Berkshire (94.1 per cent), Sunderland (95.4 per cent), Dorset (95.3 per cent) and Cumbria (also 95.3 per cent).

And more than 19 in 20 youngsters aged five are double-jabbed in North Tyneside and Leicestershire, the NHS Digital statistics also revealed.

Overall, the figure for uptake of both doses by the time children turn five is 86.6 per cent.

And the national figure for the proportion of two-year-olds having had their first dose is one of the lowest figures for the last decade, which included record-high uptake of 92.7 per cent in 2013.

The proportion of children receiving the MMR vaccine had been falling since 2015, but last year increased for the first time in six years to 90.6 per cent. However, the figure has now dropped again to just 90.3 per cent of children across the UK.

How do the MMR vaccines work?

The MMR vaccine is a safe and effective combined vaccine.

It protects against three illnesses: measles, mumps and rubella.

The highly infectious conditions can easily spread between unvaccinated people.

The conditions can lead to serious problems including meningitis, hearing loss and problems during pregnancy.

Two doses of the MMR vaccine provide the best protection against measles, mumps and rubella.

The NHS advises anyone who has not had two doses of the MMR vaccine to ask their GP for a vaccination appointment.

Two doses of the jab protects around 99 per cent of people against measles and rubella, while around 88 per cent of people are protected against mumps.

Source: NHS

Advertisement

The NHS began dishing out the vaccine as a single dose in 1988, before administering two doses from 1996.

Before MMR vaccines were available, there were hundreds of thousands of measles cases in epidemic years. But the disease was effectively eradicated in the UK after the vaccine was introduced.

However, a now-discredited study by London doctor Andrew Wakefield in 1998 wrongly linked the MMR jab to autism, causing vaccine uptake rates decline and recent outbreaks in 10 to 16 year olds who missed the jabs in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Mr Wakefield conducted a study of just 12 children to support the link, but many much larger studies have found no difference in risk of developing autism from the jab.

He was later struck off by the General Medical Council, which ruled that he had been ‘dishonest, irresponsible and showed callous disregard for the distress and pain’ of children.

But his retracted study is inaccurately referred to by the anti-vax movement to spread misinformation and is used as a reason not to vaccinate children.

Between April and June this year, Public Health England confirmed there was one measles case and two mumps cases. There have been no confirmed cases of rubella reported in the UK since 2019.

However, these are only the cases that have been confirmed via lab tests, so there may have been many more that went undetected.

Professor Jonathan Ball, a virologist at the University of Nottingham, told MailOnline the MMR vaccine has ‘performed so well over the decades that we have forgotten just how serious these viruses can be, and that has led to some complacency’.

He said: ‘Measles is one of, if not the most infectious viruses, and this high infectiousness means that vaccine uptake has to be high – greater than 90 per cent – to limit the likelihood of outbreaks.

‘Any place where vaccine uptake drops below this level will see future outbreaks of disease.

‘Whilst anti-vaxx sentiment is no doubt affecting uptake in some places, that isn’t the entire picture. We need to understand what the barriers are and introduce measures to break these down.

‘It might need better education to overcome misinformation, but it will also likely need better community health services and more flexible ways to get vaccines out to patients.’

Professor Helen Bedford, an expert in children’s health at University College London Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, told MailOnline that the disparities in MMR vaccine uptake in different parts of the country is ‘a real concern because it means that many children are not protected against these diseases’.

She said: ‘Measles in particular is not only highly infectious but can be very serious. At this level of vaccine uptake there is a very real risk of us seeing outbreaks of disease.

‘We know that some parents had difficulty getting their children vaccinated during the lockdown periods in the pandemic.

‘It is never too late to have most vaccines, so it is important that parents are encouraged to take their children to catch up with any missed vaccines. If in doubt speak to your GP, practice nurse or health visitor.’

IS ANDREW WAKEFIELD’S DISCREDITED AUTISM RESEARCH TO BLAME FOR LOW MEASLES VACCINATION RATES?

Andrew Wakefield’s discredited autism research has long been blamed for a drop in measles vaccination rates

In 1995, gastroenterologist Andrew Wakefield published a study in The Lancet showing children who had been vaccinated against MMR were more likely to have bowel disease and autism.

He speculated that being injected with a ‘dead’ form of the measles virus via vaccination causes disruption to intestinal tissue, leading to both of the disorders.

After a 1998 paper further confirmed this finding, Wakefield said: ‘The risk of this particular syndrome [what Wakefield termed ‘autistic enterocolitis’] developing is related to the combined vaccine, the MMR, rather than the single vaccines.’

At the time, Wakefield had a patent for single measles, mumps and rubella vaccines, and was therefore accused of having a conflict of interest.

Nonetheless, MMR vaccination rates in the US and the UK plummeted, until, in 2004, the editor of The Lancet Dr Richard Horton described Wakefield’s research as ‘fundamentally flawed’, adding he was paid by a group pursuing lawsuits against vaccine manufacturers.

The Lancet formally retracted Wakefield’s research paper in 2010.

Three months later, the General Medical Council banned Wakefield from practising medicine in Britain, stating his research had shown a ‘callous disregard’ for children’s health.

On January 6 2011, The British Medical Journal published a report showing that of the 12 children included in Wakefield’s 1995 study, at most two had autistic symptoms post vaccination, rather than the eight he claimed.

At least two of the children also had developmental delays before they were vaccinated, yet Wakefield’s paper claimed they were all ‘previously normal’.

Further findings revealed none of the children had autism, non-specific colitis or symptoms within days of receiving the MMR vaccine, yet the study claimed six of the participants suffered all three.

Advertisement

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-10045093/Englands-MMR-vaccine-postcode-lottery-40-children-parts-London-missing-jab.html