Gavin Williamson today piled pressure on the Government’s vaccine advisory panel to sign off on plans to jab children as young as 12 against Covid.

During a round of interviews this morning, the Education Secretary said he ‘very much hoped’ the group would come down in favour of routinely inoculating youngsters aged 12 to 15.

He suggested the delayed decision was making parents anxious about sending their children back to classrooms this week after the summer break. ‘I think parents would find it deeply reassuring to have a choice of whether their children should have a vaccine or not,’ he told BBC Breakfast.

The Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) — an independent body which advises No10 on the Covid jab roll-out — is still weighing up the risks and benefits of vaccinating children.

In guidance published in July, the group said the small risk of heart inflammation from vaccines outweighed the tiny threat coronavirus poses to them. It was also not convinced that vaccinating children solely to protect adults justified the move and raised doubts about the true prevalence of long Covid in youngsters.

But pressure has been mounting on the JCVI to green light the move and bring Britain in line with US and Israel, after Covid cases skyrocketed in Scotland when classes went back after the summer break in mid-August.

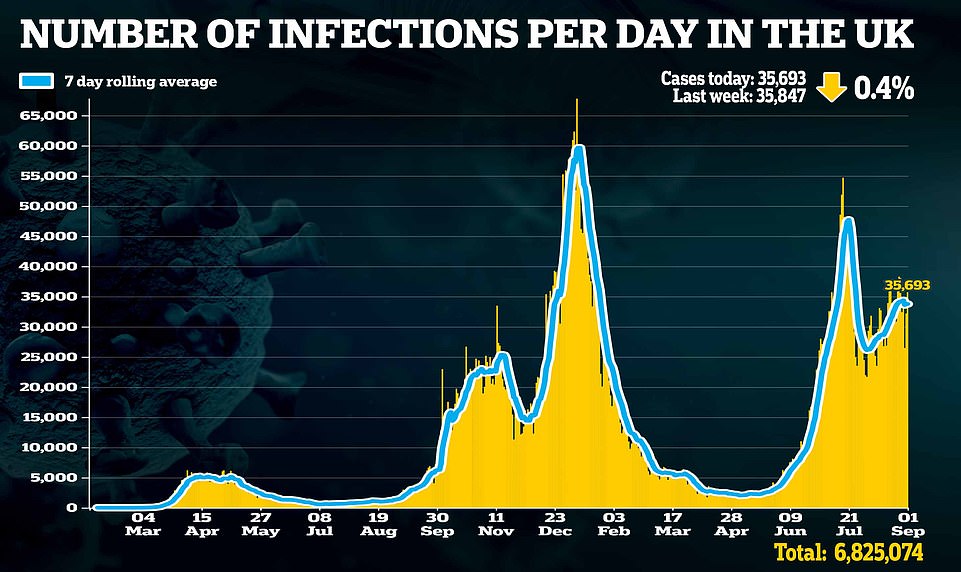

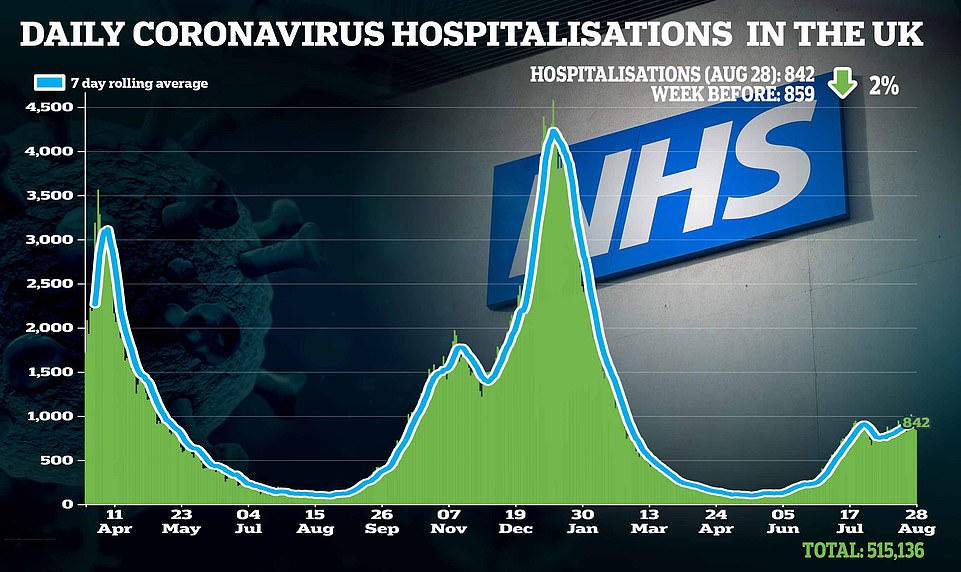

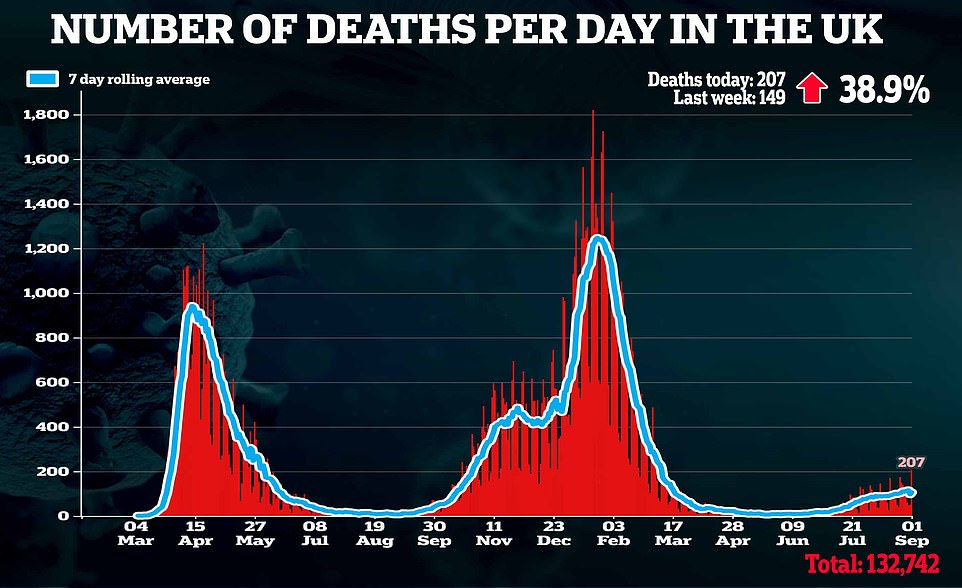

There are fears of a similar big bang in cases now that schools across the rest of the UK have started to restart. The country is already recording 35,000 infections each day and hospitalisations are creeping up.

But Professor Anthony Harnden, one of the chief scientists on the JCVI, said today the group would do what’s best for children ‘no matter what other people outside the committee think’. Only over-16s are routinely eligible at the moment but younger children who are vulnerable to live with at-risk adults can be jabbed.

A member of the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) suggested giving children one dose of Covid vaccine because heart complications are more common following the second injection.

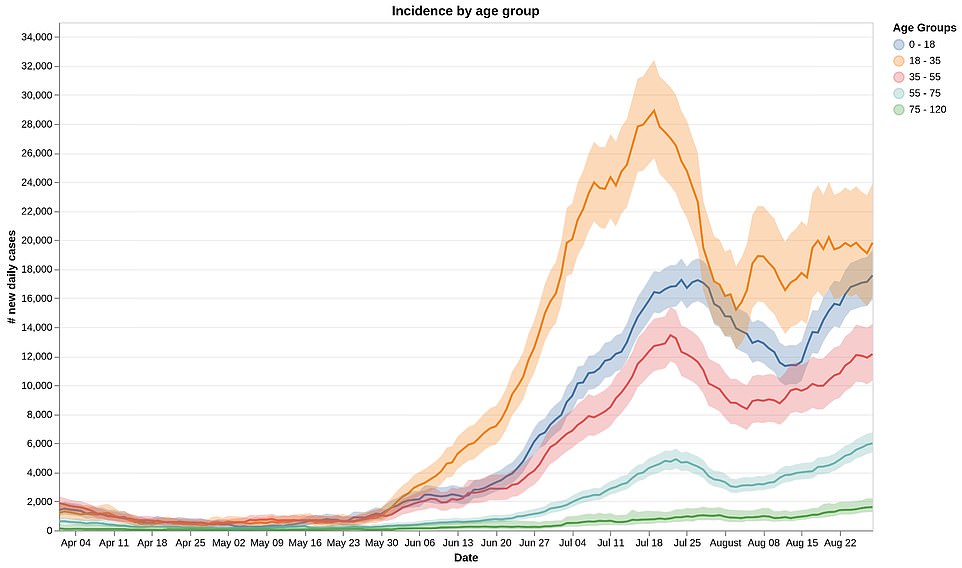

Latest estimates from a symptom-tracking app suggested under-18s had the second highest number of Covid cases in the country (blue line). Only 18 to 35-year-olds had a higher number of Covid cases (orange line). That is despite schools in England, Wales and Northern Ireland only starting to go back this week. The data is from the ZOE Covid Symptom Study

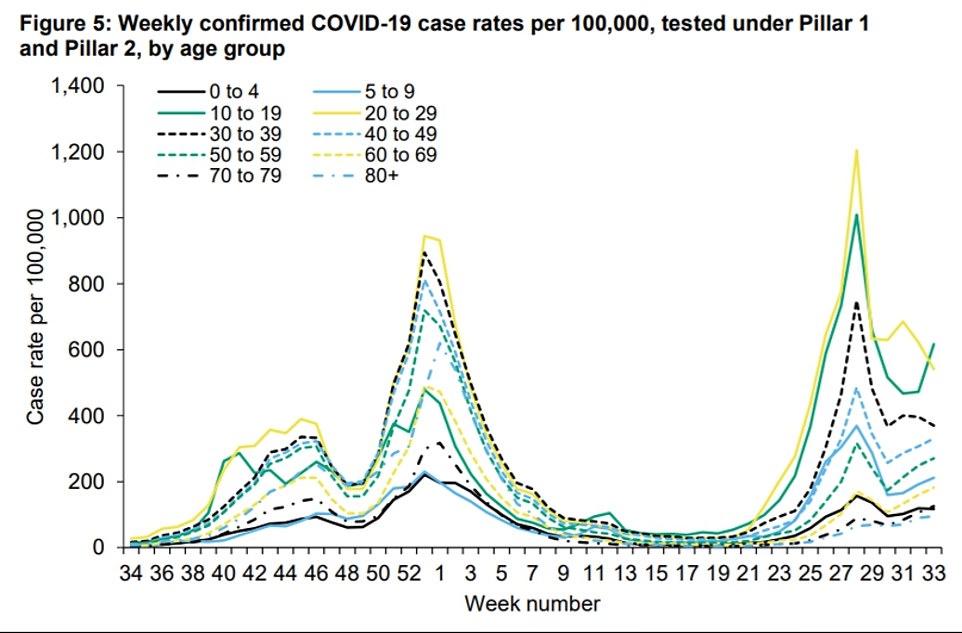

Latest Public Health England data showed Covid cases are rising fastest among 10 to 19-year-olds (grey line) and 20 to 29-year-olds (green line). Approving Covid vaccines for 12 to 15-year-olds would likely help curb the spread of the virus in the age group, scientists in favour of the move add

Speaking on BBC Breakfast, Mr Williamson made it clear he was in favour of vaccinating secondary school-aged children.

‘Probably a lot of us are very keen to hear that and very much hope that we’re in a position of being able to roll out vaccinations for those who are under the age of 16,’ he said.

‘I would certainly be hoping that it is a decision that will be made very, very soon.’

He added: ‘I think parents would find it deeply reassuring to have a choice of whether their children should have a vaccine or not. We obviously wait for the decision of JCVI.’

WHAT ARE THE PROS AND CONS OF VACCINATING CHILDREN?

Pros

Protecting adults

The main argument in favour of vaccinating children is in order to prevent them keeping the virus in circulation long enough for it to transmit back to adults.

Experts fear that unvaccinated children returning to classrooms in September could lead to a boom in cases among people in the age group, just as immunity from jabs dished out to older generations earlier in the year begins to wane.

This could trigger another wave of the virus if left unchecked, with infection spilling into older age groups and triggering more hospitalisations and deaths.

However, the rise of the Delta variant has blunted vaccines’ effect on blocking transmission which has raised further doubts.

Avoiding long Covid in children

While the risk of serious infection from Covid remains low in most children, scientists are still unsure of the long-term effects the virus may have on them.

Concerns have been raised in particular about the incidence of long Covid — the little understood condition when symptoms persist for many more weeks than normal — in youngsters.

A study by King’s College London showed fewer than two per cent of children who develop Covid symptoms continue to suffer with them for more than eight weeks.

Just 25 of the 1,734 children studied — 0.01 per cent — suffered symptoms for longer than a year.

Other studies have suggested up to half of children infected with Covid suffer from lingering symptoms months later — but they are thought to only be very mild.

Cons

Health risks

Extremely rare incidences of a rare heart condition have been linked to the Pfizer vaccine in youngsters.

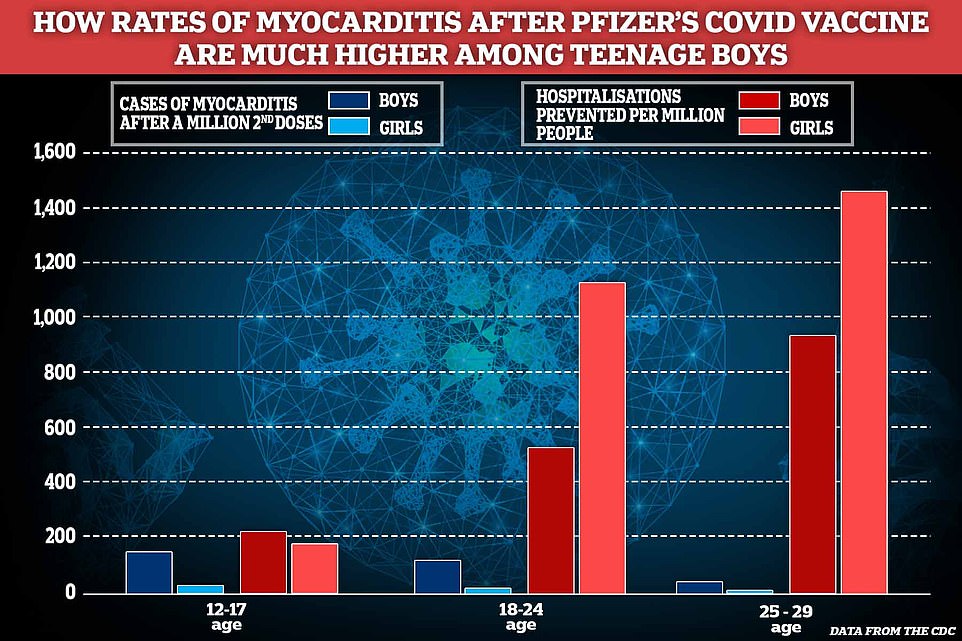

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Protection (CDC) in the US — where 9million 12- to 17-year-olds have already been vaccinated — shows there is around a one in 14,500 to 18,000 chance of boys in the age group developing myocarditis after having their second vaccine dose.

This is vanishingly small. For comparison, the chance of finding a four-leaf clover is one in 10,000, and the chance of a woman having triplets is one in 4,478.

The risk is higher than in 18- to 24-year-olds (one in 18,000 to 22,000), 25- to 29-year-olds (one in 56,000 to 67,000) and people aged 30 and above (one in 250,000 to 333,000). But, again, this is very low.

Britain’s drug regulator the MHRA lists the rare heart condition as a very rare side-effect of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines.

They said: ‘There have been very rare reports of myocarditis and pericarditis (the medical term for the condition) occurring after vaccination. These are typically mild cases and individuals tend to recover within a short time following standard treatment and rest.’

More than four times as many hospitalisations were prevented as there were cases of myocarditis caused by the vaccine in 12- to 17-year-olds, the health body’s data show.

Jabs should be given to other countries

Experts have also claimed it would be better to donate jabs intended for teenagers in the UK to other countries where huge swathes of the vulnerable population remain unvaccinated.

Not only would this be a moral move but it is in the UK’s own interest because the virus will remain a threat to Britain as long as it is rampant anywhere in the world.

Most countries across the globe are lagging significantly behind the UK in terms of their vaccine rollout, with countries in Africa, Southeast Asia and South America remaining particularly vulnerable.

Jabs could be better used vaccinating older people in those countries, and thus preventing the virus from continuing to circulate globally and mutate further, than the marginal gains to transmission Britain would see if children are vaccinated, experts argue.

Professor David Livermore, from the University of East Anglia, has said: ‘Limited vaccine supplies would be far better used in countries and regions with large vulnerable elderly populations who presently remain unvaccinated — Australia, much of South East Asia and Latin America, as well as Africa.’

Advertisement

All 16 and 17-year-olds are already being invited for the Pfizer vaccine and don’t need permission from a parent or guardian to get one.

But only under-16s who live with vulnerable people or who have immune weaknesses themselves are being invited at present.

Mr Williamson could not give a timeline for when the decision on jabbing healthy young children is expected because the JCVI is a ‘completely independent committee’.

He said: ‘They’re not there to take instructions from the Government. They will reach a decision, I’m told and I understand, very, very soon.’

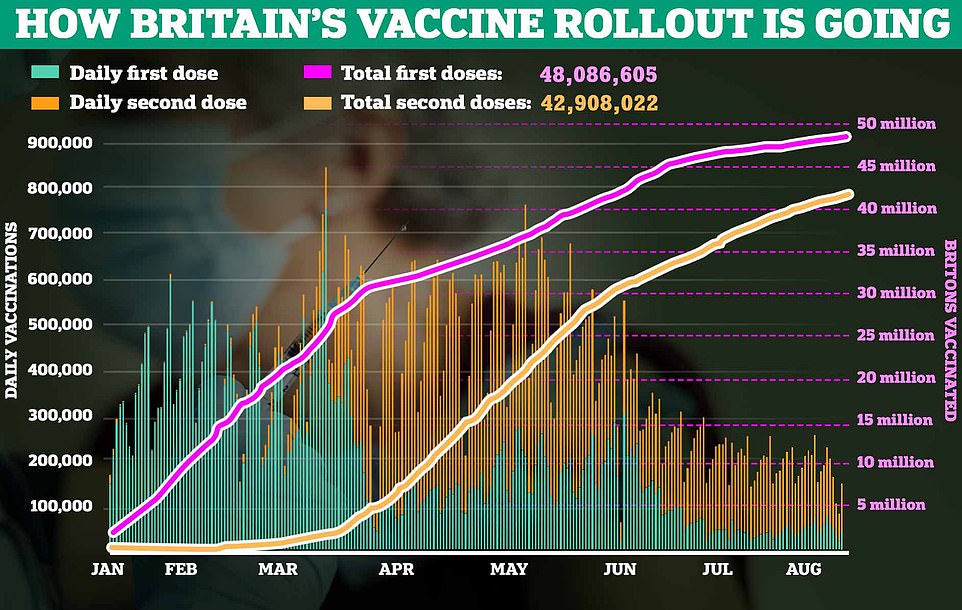

In a separate interview with Sky News, he added: ‘If we get the get-go from JCVI we’re ready, the NHS, which has been so successful in rolling out this programme of vaccination, is ready to go into schools and deliver that vaccination programme for children.’

The Government has put added pressure on the JCVI for a decision by instructing the NHS to have the staff and logistics in place to start rolling the vaccines out in schools from this week — without their parent’s consent.

But Professor Harnden said the JCVI was committed to doing what is in children’s best interests, regardless of political pressure.

He told BBC Radio 4’s Today Programme: ‘There’s many, many arguments for and against giving vaccines to 12 to 15-year-olds, and we’re deliberating on what we think as a committee is best for children.

‘And that is the key thing: whatever we decide, we will do it in the children’s best interests no matter what other people outside the committee think. And we will come to a really, really strong decision about our advice.

‘Now of course it is up to ministers as I say to make decisions, it’s not up to JCVI, but we will give some very strong advice.

‘But there are very strong arguments for vaccinating 12 to 15-year-olds, and there’s some arguments against as well and it’s very finely balanced.’

Children have only a small risk of becoming seriously ill with Covid and a vanishingly small chance of death, while Pfizer and Moderna’s vaccines are associated with rare cases of myocarditis in young people.

The JCVI said in July there was a risk of the heart inflammation in about one in 20,000 young people after being fully immunised with Pfizer’s vaccine.

The Moderna jab, which works in a very similar way, is thought to carry the same risk.

It ruled against recommending the vaccine to healthy children then because the risk of dying from the virus for them is lower than one in a million.

But the JCVI later U-turned to recommend jab for 16 and 17 year olds.

Professor Calum Semple, a child health expert who sits on SAGE, admitted that vaccinating 12 to 15-year-olds was a ‘really tricky decision’.

But he said one way to reduce the risk of myocarditis and still gain some protection against Covid would be to offer them one dose only.

He told BBC Breakfast: ‘We’ve got a really fine balancing act between a rare side effect – which is very, very rare, which is myocarditis – and the low risk (from Covid) to children themselves.

‘If however you take into the round the risks of impact on transmission to the wider society and disruption to school, so you take a broader view of the benefit of vaccination, that might shift the decision around vaccinating 12 to 15-year-olds, but that’s a really difficult judgment.

‘I would probably go for a single dose of the vaccine for 12 to 15-year-olds, as a one-off – in order to help public health generally, break transmission chains in society.

‘The rare side effect of myocarditis appears to be associated more with the second dose than the first dose.

‘So I would probably go down the path of giving one dose only, as a one-off, and then waiting until children are much older before we go for the double jab.’

Another argument for vaccinating children has been to protect them from long Covid — a poorly understood condition that leaves even asymptomatic Covid patients with lingering issues months after the infection.

Previous research suggested as many as half were struck down with long Covid.

But the largest and most robust study into long Covid’s prevalence in youngsters found the scale of the condition in children was ‘nothing like’ initially feared.

The University College London research of almost 7,000 youngsters aged 11 to 17 suggested about one in seven have symptoms three months after clearing the initial Covid infection.

Common ailments included headaches and tiredness but there was no evidence that any of the children had ‘severe’ illness as a result of long Covid.

Dr Liz Whittaker, one of the main authors of the study, said that long Covid did not appear to be a ‘severe disease’ in young people, adding: ‘Vaccines prevent severe disease.’

She also added that while the jabs offer high protection against severe Covid, they are less effective at preventing transmission. So it’s difficult to know whether [long Covid] could be prevented through vaccinating children or not.’

Meanwhile, Mr Williamson said he will ‘move heaven and earth’ to avoid shutting schools again, but he did not rule out a rise in Covid infections being caused by children going back to class.

The minister also did not exclude classes and assemblies having to take place outside during this academic year amid coronavirus outbreaks in schools.

The JCVI said in July there was a risk of the heart inflammation in about one in 20,000 young people after being fully immunised with Pfizer’s vaccine. The Moderna jab, which works in a very similar way, is thought to carry the same risk. It ruled against recommending the vaccine to healthy children then because the risk of dying from the virus for them is lower than one in a million. But the JCVI later U-turned to recommend jab for 16 and 17 year olds. The above graph shows the risks of myocarditis vs Covid among young people in the US

Scale of long Covid in children ‘nothing like’ initially feared, finds largest study of its kind

Up to one in seven children in England suffer from long Covid after recovering from the initial infection, according to the largest study of its kind.

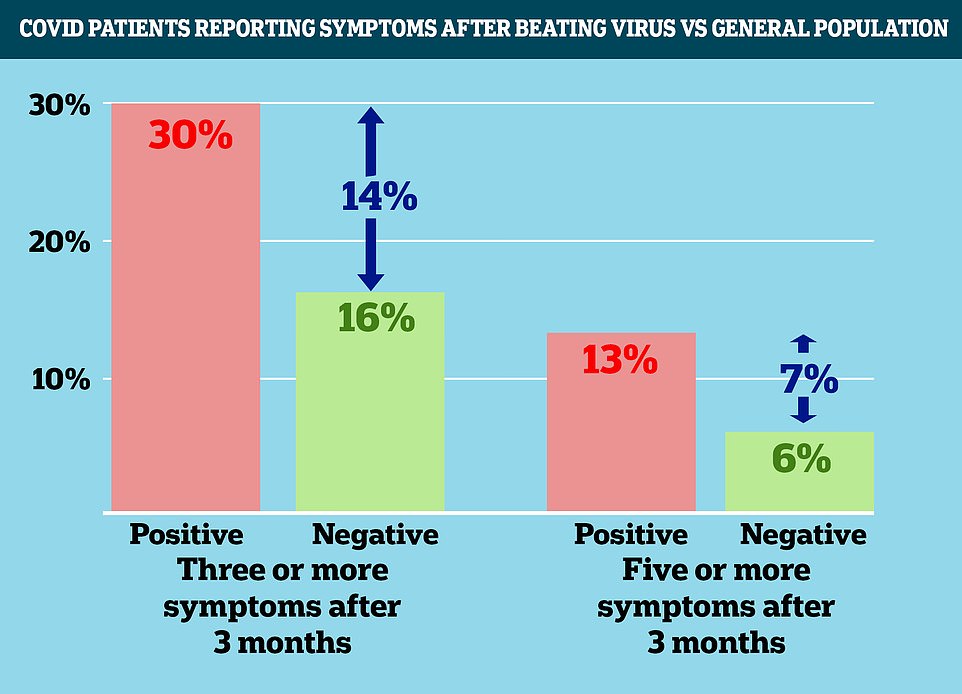

The University College London research of almost 7,000 youngsters aged 11 to 17 found 14 per cent of those who tested positive for the virus had three or more persistent symptoms three months later.

The lead scientist behind the study said the problem of long Covid in children was ‘not anything like’ the scale warned about in previous reports.

Only children who had a confirmed PCR test result were included in the research, unlike other studies, and they were compared to a control group.

Among the participants who were still feeling unwell three months after beating the virus, 7 per cent said they had five or more symptoms.

Common ailments included headaches and tiredness but there was no evidence that any of the children had ‘severe’ illness as a result of long Covid.

It comes amid a row over whether Britain should be routinely vaccinating secondary school pupils as classrooms go back and infections remain stubbornly high.

The topic has proven controversial because giving the jabs to children would be almost exclusively to protect adults from Covid.

Children are at an extremely low risk of the virus itself but previous research suggested as many as half were struck down with long Covid, which some argued was another reason to vaccinate them.

Advertisement

His comments came as pupils across England and Wales have begun to return to the classroom this week after the summer holidays, and schools in Northern Ireland have reopened.

Schools in Scotland returned a fortnight ago and the reopening is believed to have contributed to a rise in cases north of the border.

Asked if he could rule out school closures again, Mr Williamson told LBC radio: ‘I will move heaven and earth to make sure that we aren’t in a position of having to close schools.’

The minister added that he was ‘absolutely’ confident pupils will get their GCSEs and A-levels at the end of this school year after exams were cancelled for two years in a row due to the Covid pandemic.

He told LBC: ‘We’ve had two years where we’ve not been able to run a normal series of exams.

‘I don’t think anyone wants to see a third year of that.

‘We want to get back to normal, not just in terms of what the classroom experience is like but also the exam experience.’

But the Education Secretary did not rule out a rise in infections being caused by schools reopening.

After being asked repeatedly, Mr Williamson told Sky News: ‘This is why we’re doing the testing programme and we’re encouraging children to take part in it, parents, and of course teachers and support staff as well. This is a way of rooting out Covid.

‘We’re trying to strike that constant, sensible balance of actually giving children as normal experience in the classroom as possible, but also recognising we’re still dealing with a global pandemic.’

All secondary school and college pupils are being invited to take two lateral flow tests at school, three to five days apart, in England on their return.

Schools and colleges are being encouraged to maintain increased hygiene and ventilation, and secondary school and college pupils in England have been asked to continue to test twice weekly at home.

Mr Williamson did not rule out outdoor classes and assemblies having to take place in the event of outbreaks.

But he told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme: ‘It is certainly not something that we’d be expecting to see an awful lot of, especially in autumn and winter.’

Schools in England no longer have to keep pupils in year group ‘bubbles’ to reduce mixing and face coverings are no longer advised.

Children do not have to isolate if they come into contact with a positive case of Covid. Instead, they will need to get a PCR test and isolate only if positive.

The medical director of Public Health England (PHE) moved to reassure parents as pupils return to classrooms, saying schools are not the ‘drivers’ or ‘hubs’ of Covid-19 infection in communities.

Dr Yvonne Doyle told BBC Breakfast: ‘There’ll be extra cleaning and hygiene, advice on ventilation (and) the testing is extremely important.’

The research surveyed more than 3,000 children who tested PCR positive between January and March. They were compared to a similarly-sized group who tested negative in the same period. When surveyed around 15 weeks after their test, 14 per cent more young people in the positive group had three or more symptoms. One in 14, or 7 per cent more, in the positive group had five or more symptoms

She added that authorities had anticipated Covid-19 outbreaks as schools reopened, saying they are ‘part of normal practice’.

But Professor Semple said schools are likely to be a ‘greater part of the problem’ when it comes to spread of coronavirus than they previously were, and compared with workplaces where the majority of adults are vaccinated and many continue to work from home.

As pupils return to classrooms, schools in England can sign up with this year’s external tuition providers through the Government’s National Tutoring Programme (NTP) to offer pupils catch-up support.

The Department for Education (DfE) has said up to six million pupils are set to benefit from catch-up tuition for lost learning over the next three years under a ‘tutoring revolution’ in schools.

Scientists at war over jabbing children: Experts say youngsters may get ‘better and longer immunity’ if they catch Covid naturally — but others warn virus could ‘tear through’ country again without vaccines in schools

Scientists were at war over vaccinating children against Covid after it was revealed the NHS has put plans in place to jab secondary school pupils without their parent’s consent.

Health service bosses have told trusts to be ready to roll out jabs to all 12 to 15-year-olds in two weeks, in a sign the country is edging closer towards routinely jabbing youngsters.

Experts pushing back against the move argued it may be better for children to catch Covid and recover to develop natural immunity than to be reliant on protection from vaccines, which studies suggest wanes in months.

Professor David Livermore, a medical microbiologist at the University of East Anglia, said the world will need to live with Covid for years if not decades — so having a generation of children with natural immunity would help prevent cases spiralling later down the line.

He said natural infection could be a ‘a better first step in the lifelong co-existence’ with the virus than rolling out the jabs.

But the move to jab healthy kids for Covid has been backed by several high profile experts who have warned the virus could ‘rip through’ the country again if children are allowed back into schools with no protection.

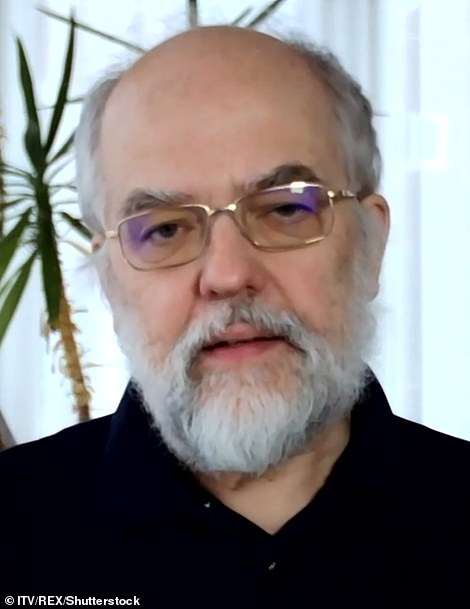

Scientists were at war over vaccinating children against Covid today. Professor David Livermore (left) says it is ‘plausible’ that immunity from natural infection could last longer for children but Professor Devi Sridhar (right) says the virus could rip through the country again

Children have only a small risk of becoming seriously ill with Covid and a vanishingly small chance of death, while Pfizer and Moderna’s vaccines are associated with rare cases of heart inflammation in young people.

Professor Paul Hunter, an infectious disease expert at the University of East Anglia, said the risks of side effects currently outweighs the dangers posed by Covid itself for most children.

And he added ‘as much as half’ of all teens would already have had the virus, referencing estimates from the Office for National Statistics, and therefore have natural immunity already and not need a jab.

Professor Hunter also said that vaccinating children would be purely for the benefit of adults, which could be seen as ethically ‘dubious’.

And Professor Tim Spector, an epidemiologist at King’s College London, told MailOnline vaccinating children would ‘use up’ Britain’s supply of jabs designated for boosters for the clinically vulnerable this winter.

But other experts are piling the pressure on the the JCVI to approve Covid vaccines for over-12s.

Professor Devi Sridhar, a global public health expert at Edinburgh University, said 12 to 15-year-olds should be offered the vaccine ‘urgently’ with the Delta variant set to ‘fly through schools’.

Britain’s medical regulator, the MHRA, has already said the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are safe and effective for the age group.

But the Joint Committee on Vaccinations and Immunisations (JCVI) — which advises No10 on jabs and is separate from the MHRA — is yet to green light to the plans.

It claims the small risk of side effects may still outweigh the benefit due to the fact young children are very unlikely to be badly ill with Covid.

The JCVI said there was a risk of heart inflammation in about one in 20,000 after a dose of Pfizer’s vaccine in guidance published last month.

It ruled against recommending the vaccine to healthy children because the risk of dying from the virus for them is about one in a million.

Professor Paul Hunter, an infectious disease expert at the University of East Anglia, said the risks of side effects currently outweighs the dangers posed by Covid itself for most children (left). Professor Tim Spector (right), an epidemiologist at King’s College London, told MailOnline vaccinating children would ‘use up’ Britain’s supply of jabs designated for boosters for the clinically vulnerable this winter

Professor Livermore told MailOnline: ‘It is clear that the vaccine-mediated protection wanes significantly within four to six months. Even government advertising acknowledges this.

‘On the other hand, reinfection remains rare among those infected in the first wave, over a year ago.

‘Accordingly it is plausible – not proven – that natural infection will give children a better first step in the lifelong co-existence that we all are now going to “enjoy” with this now endemic virus.’

He continued: ‘There is no direct reason to vaccinate children and adolescents against Covid. They are extremely unlikely to suffer severe disease if infected.

‘Rare but serious side effects have been associated with the vaccines, including blood clots and myocarditis. For older adults and the vulnerable, these are small hazards compared with those from Covid infection, and being vaccinated is obviously prudent.

‘But for children the risk/benefit ratio is far less clear, and may reverse. The JCVI initially were against vaccinating children on this logic and have provided no clear reason for a change of view.’

‘Taking these three points together I can see no good reason to vaccinate under-18s, let alone 12-year-olds.’

Other experts agreed, arguing the balance of risk still appears to lean towards not giving children a vaccine.

Professor Hunter told MailOnline: ‘At the moment I think the balance of evidence is against vaccinating 12 to 15-year-olds against Covid but I would trust the JCVI decision and be supportive if they decided this group needs to be inoculated.

‘I have heard a number of people whose opinion I value and trust argue against it — including people who are on the JCVI — and they will have spent a lot of time going through all the data.’

He continued: ‘The first issue is that young people in particular are at an increased risk of side effects from vaccines compared to older people.

‘There are side effects – and it does appear to be the case – that myocarditis is a risk particularly in young boys who get the Pfizer vaccine.

‘So in younger people vaccinating is not a risk-free option.’

He said a report in the last week of July showed two-thirds of 17-year-olds are already immune to the virus from natural infection, and now now the figure is likely to be as high as three quarters.

Around half of the 12- to 13-year-olds are likely to have antibodies already, he said, and the jab ‘won’t hae any real benefit’ to them as a result.

Professor Hunter said: ‘If we are going to be vaccinating these children it has got to be in their interest, not in ours.

‘It is one thing to say have a vaccine to protect your health, but quite another thing to persuade you to have a vaccine to protect my health. One is entirely ethical and the other is dubious.’

And Professor Spector said while vaccinating would reduce cases ‘in an ideal world’, in the immediate term it could take up supply intended for booster shots to older, more vulnerable people who’s own immunity from vaccines given earlier in the year may be on the wane.

Professor Spector said: ‘With vaccinating children you are going to reduce numbers of infections, but if you do that that means you use up your boosters and so you risk more deaths and hospitalisations at the other end of the spectrum.

‘In the ideal world I would be in favour of doing both [booster shots for the elderly and vaccines for over-12s] but I definitely think we should be giving boosters to kids that have had natural infections.’

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-9950603/Gavin-Williamson-urges-JCVI-hurry-make-decision-vaccinating-12s-against-Covid.html