Giving 12 to 17 year olds two doses of a Covid vaccine would prevent thousands from being hospitalised with the virus this autumn, a controversial study suggests.

Experts behind the research have called for the UK to reconsider its current roll-out, which will see youngsters only given a single Pfizer jab.

Health officials have held back on recommending the full course because of the very rare risk of heart inflammation associated with the second shot.

The study looked at rates of Covid infection, hospital admission and death among teenagers in previous waves of the pandemic in the UK.

It estimated that if Covid cases in secondary schools continue at their current rate, then a two-dose regimen could prevent 4,430 admissions and 36 deaths in teens compared to a single injection.

The team of researchers, led by Queen Mary University, insisted this benefit ‘clearly’ outweighed the small risk of myocarditis, which affects about one in 10,000 and is usually mild.

They claimed the risk would only outweigh the benefit of vaccination if infection rates in teens were to suddenly drop to tiny levels.

While most patients who develop myocarditis after their jab suffer only a mild bout of the disease, scientists are still unsure about the long term consequences of the inflammation of the heart.

Academics today hit back at the ‘questionable’ findings of the study, which failed to differentiate between the Covid risk to healthy and vulnerable children.

The analysis was carried out by several members of Independent SAGE and is published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine.

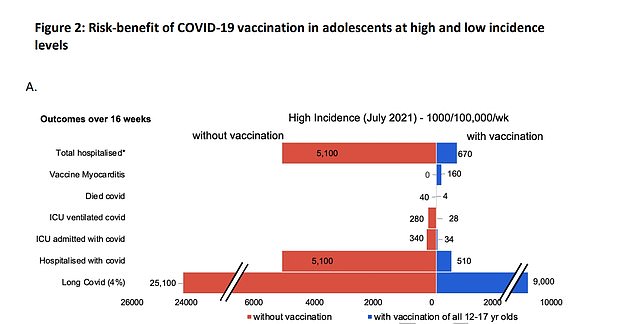

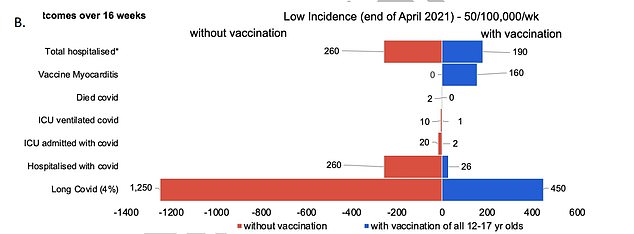

The latest study looked at rates of Covid infection, hospital admission and death among teenagers in previous waves of the pandemic in the UK. It estimated that if Covid cases in secondary schools continue at their current rate, then a two-dose regimen could prevent 4,430 admissions and 36 deaths in teens compared to a single injection. This finding was based on the assumption that Covid case rates in teens rises to 1,000 by 100,000 this autumn

The study said that the benefit of double-dosing outweighed the risk of myocarditis, heart inflammation linked to the second injection, in every scenario unless the case rate drops below 30 per 100,000 teenagers per week (shown here)

Independent SAGE lobbied the Government to pursue a ‘zero Covid’ strategy and was one of the leading pro-lockdown groups.

The study’s calculations are based on the assumption that 0.82 per cent of Covid-infected children end up being hospitalised — the equivalent of one in every 120 youngsters.

This is up to 80 times higher than the figure provided by No10’s vaccine advisory panel, the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI).

Fourteen-year-old Jack Lane became one of the first to benefit from the extension of Britain’s jab rollout today. He received his vaccination at Belfairs Academy in Leigh-on-Sea, Essex

Britain’s daily Covid cases rise by 7% in a week as outbreak continues to grow – but deaths and admissions dip

Covid cases have risen by seven per cent across the UK, marking the twelfth day in a row that the outbreak has grown week-on-week.

Department of Health bosses posted another 36,722 infections, a rise of 6.6 per cent compared to the 34,460 positive tests recorded last Wednesday.

Britain’s infections have increased steadily after schools reopened this month, allowing the virus to spread among youngsters and be passed on to their parents.

Meanwhile, another 150 deaths were added to the Covid death toll, while 659 infected Britons were hospitalised.

Both figures – which lag several weeks behind cases because of how long it can take for infected patients to become seriously ill – are down 10 per cent compared to last week’s data.

The latest figures means an average of 35,204 people tested positive on any given day in the last week.

Nearly 8million Britons have received a positive lab-reported or lateral flow result since the beginning of the pandemic. At the peak of the second wave last winter, some 81,480 people tested positive on a single day.

The vast majority of the daily infections were spotted in England. Some 29,036 cases were recorded, a rise of 6.3 per cent on the 27,317 positive tests last week.

Meanwhile, cases have fallen by 16.7 per cent to 2,997 in Scotland after the country saw its biggest surge in infections since the pandemic began after pupils returned to classrooms on August 16.

Infections in Scotland peaked at 7,523 on September 2 and have been falling steadily since then.

Advertisement

The group originally ruled against routinely inoculating all over-12s because it concluded that Covid posed such a tiny risk to their health.

The group, comprised of some of the country’s top experts, justified its decision with data which suggested the hospitalisation rate was at most 0.04 per cent — or one in every 2,500 infected youngsters.

Its lower-end estimate, based on figures from the second wave of Britain’s outbreak, was just 0.01 per cent — the equivalent of one in every 10,000.

NHS coronavirus statistics do not give an exact age breakdown of admissions, meaning it is impossible to confirm the figure for 12-17 year olds.

But the health service’s data does show that 8,572 children have been admitted with Covid or tested positive on a ward since the start of the pandemic.

It would imply the risk of children being hospitalised with coronavirus is around 0.15 per cent, with England’s chief medical officer Professor Chris Whitty last week telling MPs that the Government’s top scientists believed around half of children had already been infected.

That calculation is based on an estimate from the Office for National Statistics (ONS), which calculated there were around 12million under-18s living in England in 2020.

NHS Covid statistics also do not differentiate between the number of children who actually required medical care to treat their infection, from youngsters who incidentally tested positive.

Dr Alasdair Munro, clinical research fellow in paediatric infectious diseases, University of Southampton, described the findings as ‘limited’.

He pointed out that the research did not look at the difference in effectiveness between one and two doses.

‘There are some important limitations to this analysis which make it of limited use given the current vaccination policy in the UK,’ Dr Munro said.

‘Most importantly, it does not attempt to qualify the difference between a single dose of vaccination compared to two doses.

‘This is current UK policy, and was made on the basis that a single dose offers the vast majority of the benefit of reductions of risk of hospitalisation and death, and avoids the worst of the potential adverse events of myocarditis, especially in young males.

‘Without being able to offer a comparison of one vs two doses (which was presented in the JCVI analysis), this does not add to the current discussion.’

He also warned that the study did not compare the difference in risk of severe Covid between healthy children and those with underlying health conditions.

Children with comorbidities have already been double-jabbed.

Removing this group from the analysis would have brought down the overall Covid risk, Dr Munro said.

‘There should have been an attempt made to account for this, as was done in the JCVI analysis,’ he added.

‘Without accounting for the differences between a single and double dose strategy, or the differential in risk between children with comorbidities and otherwise healthy children, this analysis doesn’t seem to bring us further forward in the discussion.’

Earlier this month the JCVI said it could not recommend Covid jabs for healthy 12 to 15-year-olds because the direct benefit to their health was only marginal. It also looked at the risk of health inflammation – known as myocarditis – in young people given the Pfizer vaccine, which was still very small but slightly more common after a second dose

As of September 15, around 680 out of every 100,000 10 to 19-year-olds were testing positive for Covid every week.

The study warned that if this rate rises to more than 1,000 per week then a double-dose strategy could avert 4,430 hospital admissions and 36 deaths over 16 weeks.

If cases plummet to 50 per week then vaccination might only stop 70 admissions and two deaths in that time.

It said that the benefit outweighed the risk in every scenario unless the case rate drops below 30 per 100,000 teenagers per week.

The study also suggests that thousand of potential cases of long Covid could be averted.

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-10041743/Giving-children-two-doses-Covid-jab-prevent-thousands-hospital-admissions-study.html