In 1981, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published a report on a rare lung infection in five ‘previously healthy young men in Los Angeles’.

It suggested a ‘cellular-immune dysfunction related to a common exposure’ and a ‘disease acquired through sexual contact’. The patients were described as ‘homosexuals’. Two had died.

It was the first mention of what a little over a year later became known as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, or AIDS.

Although the link hadn’t yet been made, at the same time, worried doctors in San Francisco and New York were seeing gay men who developed Kaposi’s sarcoma, cancerous lesions affecting the skin and mucous membranes.

Experts had been baffled. The disease was normally only seen in the elderly or in transplant patients.

Reliving the era: Channel 4’s drama It’s A Sin tells how AIDS hit the gay community in the 1980s

Meanwhile, in London, at St Mary’s Hospital, immunologists had taken blood from hundreds of gay men who were suffering from swollen glands in the neck, armpits and groin – a sign the body is trying to fight an infection – and discovered many had similar, inexplicable immune system abnormalities.

Within a year, similar stories began emerging in countries across Europe and Africa.

Possible reasons, no doubt steeped in the prejudices of the time, were floated: was it drug-related? Or caused by the body becoming ‘overloaded’ by recurrent sexually transmitted infections? Was it genetic?

Indeed, before it was AIDS, for a short time it was called gay-related immune deficiency, or GRID – although it quickly emerged that heterosexuals were also at risk.

Within a few years of those first cases, the cause was identified: first it was called LAV/HTLV-III, then later, the human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV.

The virus – which had not been seen in humans before – attacks the immune system, weakening it. The body quickly succumbs to infections it would normally bat away.

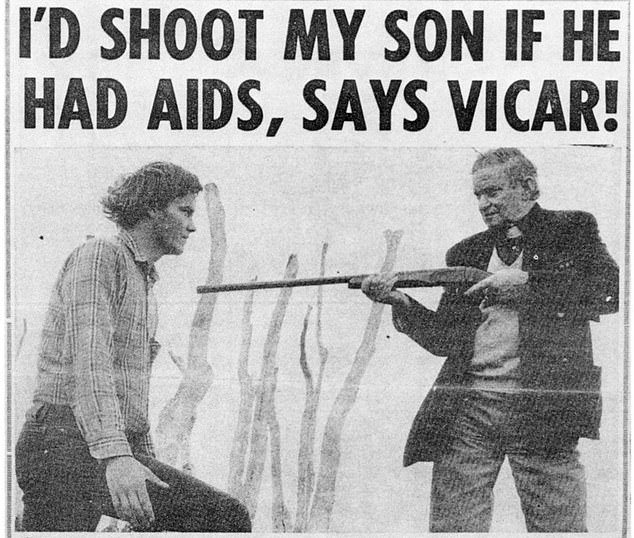

Rampant prejudice: 1986 news report indicating the terrifying hysteria and homophobia of the time aimed at anyone with AIDS

Blindness, severe muscle wasting, agonising sores and abscesses, and dementia were often seen. The decline seen in previously robustly healthy and often young individuals was breathtakingly fast.

When the discovery of HIV was announced in America, the US’s then secretary of health Margaret Heckler suggested that a vaccine would be ready for testing within two years – a prediction that, at the time, raised eyebrows among immunologists for being optimistic.

And, as we all know now, it was wide of the mark. Indeed, an effective vaccine has never been found.

June of this year marks 40 years since that first case report, in which time HIV has infected an estimated 75 million people worldwide.

More than 150,000 cases have been recorded in Britain, and nearly 59,000 here have lost their lives. But today the diagnosis of HIV is no longer a death sentence.

Modern medicines mean for most in Britain it’s more like a kind of manageable, chronic disease – with many patients expected to have a normal life expectancy.

There are also drugs that can stop people contracting the virus, and more recently there have been breakthroughs that mean the prospect of a cure is on the horizon.

It’s a far cry from the hysteria, homophobia and anguish that overshadowed the early decades of the AIDS epidemic, which has been perfectly captured by Channel 4’s hard-hitting drama It’s A Sin.

The series follows a group of young friends whose lives are destroyed by HIV in the 1980s, and has attracted more than 6.5 million views on streaming platform All 4 over the last month.

But behind the human tragedy is another story: a relentless scientific hunt for answers, of astonishing medical breakthroughs and misfires, and experts and activists across the globe united in a shared goal, to find an end to all the death and suffering.

Today, the picture is one of hope. But it has been a long and winding road.

Marchers on a Gay Pride parade through Manhattan, New York City, carry a banner which reads ‘A.I.D.S.: We need research, not hysteria!’ in June 1983

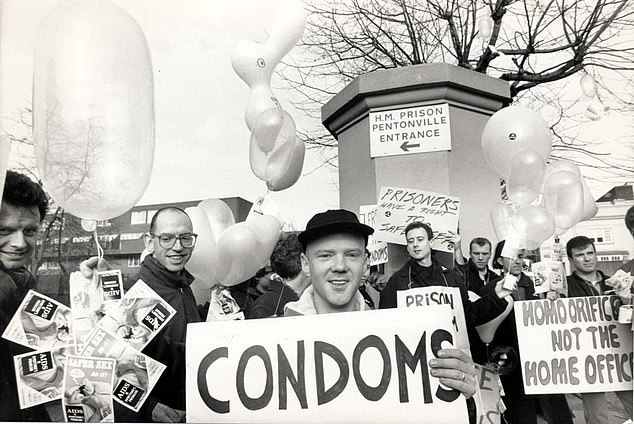

Pictured: Singer Jimmy Sommerville marches with Act Up outside Pentonville Prison in London

Recalling those early days, back in the 1980s, HIV expert Dr Duncan Churchill said: ‘It was unlike anything I’d ever seen before, large numbers of men in their 20s, 30s and 40s dying, with no obvious solution.

‘As a newly qualified doctor with a special interest in infectious diseases, it was a medical mystery that sparked my interest.’

Dr Churchill now works at Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust, but treated patients on the UK’s first dedicated AIDS ward at the Middlesex Hospital – opened by Princess Diana in 1987.

He added: ‘I felt a strong connection with the patients because of the prejudice they faced. There were often rude comments thrown around.

‘Parents visiting the ward couldn’t face the thought their son was dying of AIDS – or even that they were gay. We were forced to cover up signs with the word AIDS on it, in case it upset visitors.’

Experts immediately knew tackling this disease was no easy task, due to the unique characteristics of the HIV virus. HIV is what’s known as a retrovirus, which are rarely seen in humans. The virus is zoonotic – like Covid, it passed from animals to humans.

Studies have now shown the ‘leap’ was likely to have happened in the 1920s, in central Africa – and genetic analyses of viral samples now suggest it arrived in the US in about 1968.

Diana, Princess of Wales comforts an AIDS patient at Middlesex Hospital in 1991

But the sexual liberation of the 1970s, combined with the rise in international travel, increased its circulation. One of the reasons HIV proved so difficult to combat lies in the way it behaves.

Most other viruses hijack the body’s cells by injecting their viral DNA into it, and replicating. Treatments can target this DNA, programming the immune system to spot it, and fight it off. Retroviruses, on the other hand, are far more difficult to target.

Once the virus – carried in blood and other bodily fluids – enters the body, it infects cells by mixing its own genetic material with human DNA in the cell.

This produces a mutant cell, which spits out thousands of versions of itself in minutes, and are largely undetectable by the immune system. Due to this process, viral copies are fast-changing, so targeted treatments or vaccines quickly become useless.

Worse still, vaccines rely on a group of healthy immune cells, called CD4 T-cells, to initiate the fighter response. These are the exact cells the HIV virus targets.

In the mid-1980s, US health watchdogs initiated animal trials of an HIV vaccine, which used a genetically engineered protein to provoke human antibodies that fight against HIV. But subsequent human trials proved fruitless.

‘HIV is a total b****** of a virus, excuse the language,’ sums up Dr Laura Waters, HIV expert and chair of the British HIV Association.

‘The starting point for vaccines is to find human antibodies that fight against the infection – but HIV doesn’t trigger any that protect against the infection.

‘So scientists weren’t sure what to do. Funding for vaccines declined because none proved particularly effective.’

Early drugs focused on blocking an enzyme that helps the virus replicate when it first enters the cell.

Under mounting pressure – with fears of the epidemic spiralling out of control, potentially infecting and killing millions a year – health chiefs in the US fast-tracked medical trials into one drug, called Zidovudine, or AZT, previously used in cancer treatment.

In 1987 – after just 20 months of research – AZT was approved in the US and the UK.

But, despite the drug’s ability to extend life by roughly three years, it caused severe side effects: heart problems, nerve damage, debilitating nausea and liver disease.

Dr Waters said: ‘The drugs were toxic. Some patients have been left with disfiguring fat loss from their face, because the medication destroyed their healthy fat cells.

‘Others have permanent nerve damage, or diabetes. But, equally, I have patients who might be dead if it weren’t for those drugs.’

AZT also stopped working after a few months, due to the rapid mutations of the virus. The drug was reformulated, buying patients more time – but only a couple of years.

But then came a breakthrough. Medics from the US’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases found a combination of two versions of AZT and a third type of medication called a protease inhibitor could suppress the virus to undetectable levels, slashing deaths.

This strategy tackled the virus at various points within its life cycle, stopping it from infecting cells, mutating rapidly and spreading around the body.

Dr Waters began her career just as the new triple therapy, known as antiretroviral therapy, or ART, was approved for use in the UK, in 1996.

‘It was an incredibly exciting time because research for HIV was developing more rapidly than many other areas of medicine,’ she says. Every year there was another evolution that saved thousands more lives.

‘Suddenly it was no longer a death sentence, and people could get on with their lives, living into their 60s and 70s.’

By the early 2000s, survival had rocketed and, thanks to various reformulations by manufacturers, drug side effects were, according to experts, close to zero.

Pharmaceutical giant Moderna – famed for its Covid-19 vaccine – may have finally cracked an HIV vaccine. Pictured: Stock image

‘Starting treatment within a few days of infection is ideal, so the virus doesn’t have a chance to properly set in,’ says Dr Waters. ‘For most people, antiretroviral therapy (ART) suppresses the virus to the extent it is not detectable in the blood, or bodily fluids.’

While initially patients had to take large numbers of tablets, by the mid 00s, the three drugs had been combined into one daily pill.

‘Making sure people actually took their drugs was a challenge,’ says Dr Michael Brady, HIV consultant at London’s King’s College Hospital.

‘Having to take handfuls of pills a day is a constant reminder of their illness. The combination pill dramatically improved adherence rates.’

By 2000, at least a third of people with HIV in the UK were taking ART treatment, with deaths slashed in half.

Researchers have since developed injections of ART – given every two months – negating the need for any pills, are expected to be available in the next year.

According to Dr Waters, reaching this stage wasn’t only down to effective treatment.

Fast, easily available testing, fuelled by easier access to more local specialist sexual health centres across the UK, and the development of rapid tests, including those done at home, boosted diagnosis, getting patients on to crucial treatment, faster.

Between 2000 and 2005, new HIV diagnoses leapt from roughly 3,000 a year to 8,000, helped by routine testing for all women going into hospital to give birth.

This promising picture set the stage for an ambitious new target set by the United Nations in 2012. Countries were urged to reach ’90-90-90′: 90 per cent of people living with HIV diagnosed, 90 per cent on treatment and 90 per cent of those on drugs with viral levels so low, it’s undetectable in tests.

A pill a day and I’m fitter than ever

When Becky Mitchell was diagnosed with HIV eight years ago, she admits: ‘My first question to my doctor was: ‘What will happen to me?’

The 46-year-old fitness trainer from Devon says: ‘I worked with someone with HIV, so I knew it wasn’t a death sentence, but it was so unexpected.

My first thought was that I couldn’t get ill, because I had various sporting events coming up.’

When Becky Mitchell was diagnosed with HIV eight years ago, she admits: ‘My first question to my doctor was: ‘What will happen to me?’

Today though Becky says she feels ‘better than ever.’

Started on antiretroviral therapy immediately, she now takes a single pill a day, and the virus is at undetectable levels in her blood.

‘My activity tracker tells me I have the fitness of a 20-year-old,’ says Becky, an avid cyclist. ‘My overall health is better than ever.

‘I just wish more women knew this isn’t something that only affects gay men,’ she says.

Becky was infected after sex with a former boyfriend.

‘I took it at face value when he said precautions weren’t necessary,’ she says. ‘But he knew he had HIV, and didn’t tell me.’

Becky had been feeling tired, and generally unwell, then one of the man’s ex-girlfriends alerted her to the truth, and she immediately sought a test.

She adds: ‘He’d also failed to take his HIV medicines properly – if he had, he wouldn’t have transmitted it.

‘There’s a perception you have to be promiscuous to catch it. But you don’t – it can happen to anyone.’

Advertisement

This would all lead to a reduction in the circulation of the virus, and break chains of transmission.

Then, in 2016, came another breakthrough. Trials in 14 European countries, following 1,100 gay and straight couples over eight years, showed that, despite one partner carrying HIV, not a single transmission occurred while they were taking ART medication. This was despite thousands of unprotected sex acts.

It was, says Dr Michael Brady, a ‘step change’, that made the prospect of eradicating HIV altogether finally a possibility. He said: ‘We never expected the drugs could drop the risk of passing on HIV to near zero.’

Meanwhile, for the past decade, international scientists have been experimenting with preventative drugs – given to those at risk of infection. Known as PreP, the treatment destroys proteins on the outside of viral particles that help them enter the body’s cells, stopping infection from taking hold.

Trials have shown the pill taken every day reduces transmission by 86 per cent.

In 2017, the UK became one of the first in the world to offer the treatment to all at-risk citizens. The following year, Britain hit the UN’s ’90-90-90′ target.

More recently, a series of fascinating cases have opened new research avenues.

Two men, one in London and one from the US, saw the virus vanish from their body following experimental stem-cell transplants from donors with a rare genetic mutation that provides protection against HIV.

Similar treatments have produced promising results for multiple sclerosis patients. But up to 40 per cent of those who undergo stem cell transplants, once known as bone marrow transplants, don’t survive.

More promising is that the same astonishing effect occurs with drug treatment. In 2019, a 36-year-old Brazilian man was said to be ‘cured’, when doctors were unable to find traces of HIV in his body 14 months after he stopped ART treatment.

Other hopes for a curative treatment come from astounding cases of infected patients who appear to be genetically immune to the virus – and can keep their viral load to undetectable levels, without drug treatment.

Last year, researchers found zero traces of HIV in a 66-year-old Californian woman, despite the fact she was diagnosed with the virus in 1992.

The scientists believe these outliers are somehow able to drive viral particles into a section of human DNA where the are ‘silenced’ by the immune system.

If they can figure out the gene that enables a rare few to achieve this, a cure would be at their fingertips.

Elsewhere, pharmaceutical giant Moderna – famed for its Covid-19 vaccine – may have finally cracked an HIV vaccine.

The jab uses sophisticated gene-editing technology to train the immune system to produce a variety of HIV-like particles, to familiarise the body with many mutations. It is currently undergoing human trials.

Today, 97 per cent of people living with HIV in Britain are non-infectious, thanks to ART treatment.

The battle is far from over in other countries, with hundreds of thousands of infections a year occurring, mostly in Africa and Eastern Europe.

But UK new diagnoses are under 4,000 a year and dropping by ten per cent annually.

And so, last year came yet another target, this time from the UK’s Health Secretary, Matt Hancock: no new infections by 2030.

Will we reach it? Dr Waters is cautiously optimistic.

‘It’s possible,’ she says. ‘The key is helping people not to be afraid of HIV, by telling them a diagnosis is not life-limiting, it’s just somewhere in the background.

‘A diagnosis can even prompt positive, healthy changes in people’s lives. If I’d have said that just a couple of decades ago, people would have thought I was crazy.’

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-9281675/How-science-FINALLY-brink-beating-AIDS-40-years-32-million-global-deaths.html