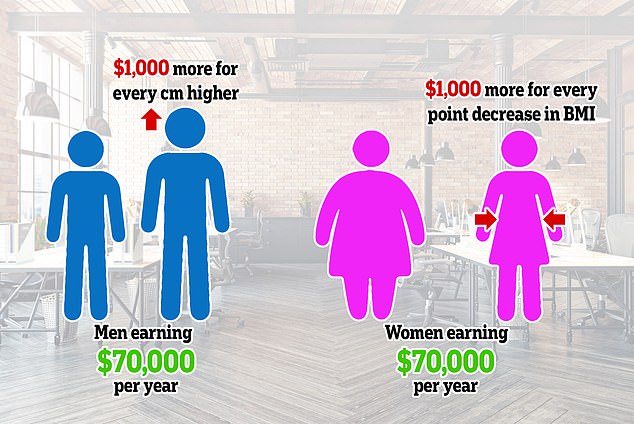

Short men and obese women earn up to $1,000 (£700) less per year than their taller, skinnier counterparts, according to a new study into body shape and salary.

This is evidence of a long suspected ‘beauty premium’ that suggests physical attractiveness demands a higher value in the labour market, according to lead author Suyong Song from the University of Iowa.

Researchers examined data from 2,383 volunteers, including whole body scans and information on their family income and gender.

They found that in men earning over $70,000 (£50,000) per year, a centimetre increase in height was worth $1,000 (£700) extra in income per year.

For women earning the same amount, every single point decrease in BMI was worth an extra $1,000 (£700) per year in their pay cheque, the researchers discovered.

The authors say this shows the importance in accurately measuring body shapes when it comes to creating public policies on mitigating discrimination and bias.

Short men and obese women earn up to $1,000 (£700) less per year than their taller, skinnier counterparts, according to a new study into body shape and salary

The study found that in men earning over $70,000 (£50,000) per year, a centimetre increase in height was worth $1,000 (£700) extra in income per year (stock image)

WHAT IS THE BEAUTY PREMIUM IN EMPLOYMENT?

Researchers claim a ‘beauty premium’ exists within the labour market.

This is where employers value attractiveness in employees when deciding salary and in hiring.

A study by the University of Iowa revealed that taller men and skinnier women earned up to £700 more per year than short men and fatter women.

Other studies have found that women who wear makeup are seen as more trustworthy than women who don’t.

Although a 2018 study by the University of Massachusetts found that people perceived as ‘very unattractive’ earn more than better looking peers.

This was likely due to ugly people being less open to new experiences and more likely to commit to their job, the team behind the research said.

A study in 2006 by Wesleyan University found that employers thought beautiful people were more productive even when only interviewed over the phone.

This suggests that the confidence that can come with being beautiful allows people to present themselves better even when not visible.

Advertisement

‘I have been curious of whether or not there is physical attractiveness premium in labor market outcomes,’ Song told PsyPost, about the idea behind the study.

One of the problems previous studies have had is that they rely on self reported body measurements, or errors in how the body is measured.

‘Most previous studies often defined physical appearance from subjective opinions based on surveys,’ Song explained.

He said a key challenge was also defining body shapes from these body measurements, as simple self reported responses were too simple.

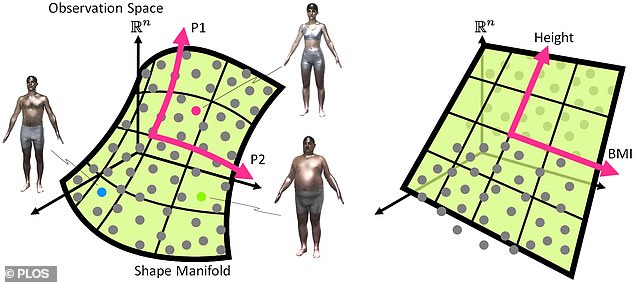

To overcome this problem the team turned to data gathered by the Civilian American and European Surface Anthropometry Resource (CAESAR) project that was conducted by the US Air Force from 1998 to 2000.

As well as detailed demographic information, body measurements made with a tape measure and calliper body measurements, it included 3D whole-body scans.

These scans allowed the researchers to feed the data on 2,383 individuals into a machine learning algorithm to identify physical features and find patterns.

‘The findings showed that there is a statistically significant relationship between physical appearance and family income and that these associations differ across genders,’ Song told PsyPost.

‘In particular, the male’s stature has a positive impact on family income, whereas the female’s obesity has a negative impact on family income.’

The data uncovered through the machine learning study revealed specific trends.

‘One centimetre increase in stature is associated with approximately $998 increase in family income for a male who earns $70,000 of the median family income,’ the team reported in the paper published in PLOS One.

For women ‘one unit decrease in obesity is associated with approximately $934 increase in the family income for a female who earns $70,000 of family income.’

‘The results show that the physical attractiveness premium continues to exist, and the relationship between body shapes and family income is heterogeneous across genders,’ Song went on to explain.

‘Our findings also highlight importance of correctly measuring body shapes to provide adequate public policies for improving healthcare and mitigating discrimination and bias in the labor market.’

They used machine learning to examine data from 2,383 volunteers, including whole body scans and information on their family income and gender

The team has suggested that awareness that this form of discrimination exists should be promoted in the workplace and tackled through training.

They also say that mechanisms to minimise the bias through hiring and promotion processes should be encouraged, including blind interviews where the hiring manager doesn’t see the candidate during the interview process.

There are limitations, as the data set only includes family income rather than individual income – so other factors could play into the income disparity.

This is evidence of a long suspected ‘beauty premium’ that suggests physical attractiveness demands a higher value in the labour market, according to lead author Suyong Song from the University of Iowa

‘This opens up additional channels through which physical appearance could affect family income,’ Song explained.

‘In this study, we identified the combined association between body shapes and family income through the labor market and marriage market.

‘Thus, further investigations with a new survey on individual income would be an interesting direction for the future research.’

The findings have been published in the journal PLOS One.

OBESITY: ADULTS WITH A BMI OVER 30 ARE SEEN AS OBESE

Obesity is defined as an adult having a BMI of 30 or over.

A healthy person’s BMI – calculated by dividing weight in kg by height in metres, and the answer by the height again – is between 18.5 and 24.9.

Among children, obesity is defined as being in the 95th percentile.

Percentiles compare youngsters to others their same age.

For example, if a three-month-old is in the 40th percentile for weight, that means that 40 per cent of three-month-olds weigh the same or less than that baby.

Around 58 per cent of women and 68 per cent of men in the UK are overweight or obese.

The condition costs the NHS around £6.1billion, out of its approximate £124.7 billion budget, every year.

This is due to obesity increasing a person’s risk of a number of life-threatening conditions.

Such conditions include type 2 diabetes, which can cause kidney disease, blindness and even limb amputations.

Research suggests that at least one in six hospital beds in the UK are taken up by a diabetes patient.

Obesity also raises the risk of heart disease, which kills 315,000 people every year in the UK – making it the number one cause of death.

Carrying dangerous amounts of weight has also been linked to 12 different cancers.

This includes breast, which affects one in eight women at some point in their lives.

Among children, research suggests that 70 per cent of obese youngsters have high blood pressure or raised cholesterol, which puts them at risk of heart disease.

Obese children are also significantly more likely to become obese adults.

And if children are overweight, their obesity in adulthood is often more severe.

As many as one in five children start school in the UK being overweight or obese, which rises to one in three by the time they turn 10.

Advertisement

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-9898005/Short-men-obese-women-earn-1-000-year-taller-thinner-people-study-warns.html