Millions of elderly people will still have to fork out tens of thousands for care under the Government’s new plans and it will be years before they’re introduced, meaning people in care now might miss out.

Boris Johnson has claimed that nobody in England will have to pay more than £86,000 in their lifetime to fund their care in later life as part of his controversial £12billion-a-year reforms.

But only those who have been deemed most frail and in need by their local council will be eligible for the subsidies.

Even those who are accepted will have to wait until 2023, when the cap on care payments is introduced, meaning those dependent on care now will not recoup any of the costs they rack up over the next two years.

And the subsisidies will not include ‘living costs’ in care homes, such as food, energy bills and the accommodation.

The average care home in England costs in total about £36,000 a year for each resident, with £12,000 of this going towards daily living costs.

That means it would take the average care home resident more than three and a half years to hit the cap. For those in care now, that would mean waiting another nearly six years.

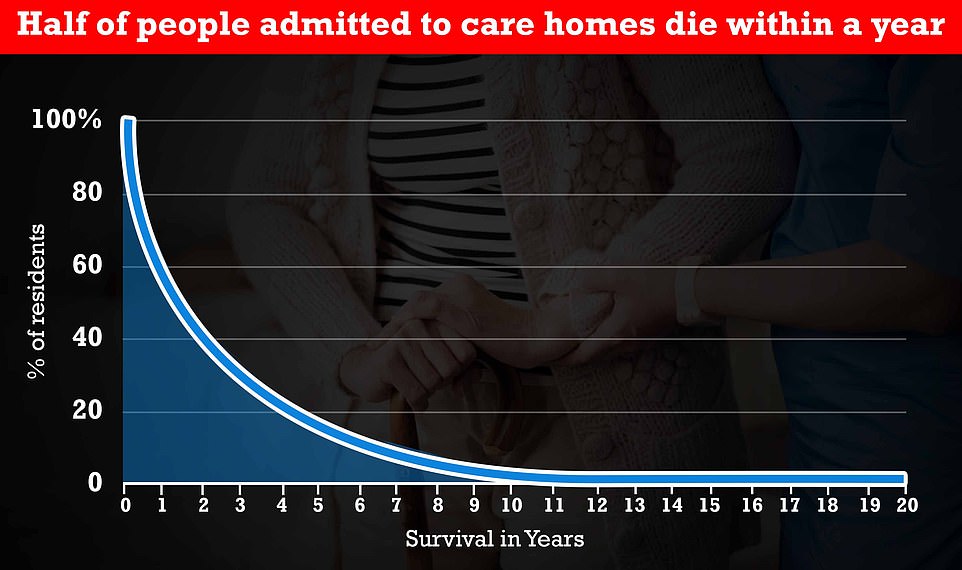

Yet official figures show half of care home residents die within a year of entering the facility, with three-quarters passing away within three years.

When the flaws in the plan were put to Mr Johnson today, he refused to deny that some people might still have to sell their homes to afford care, breaking yet another manifesto promise.

When pressed by Labour leader Keir Starmer on the issue, Mr Johnson said: ‘This is the first time that the state has actually come in to deal with the threat of these catastrophic costs, thereby enabling the private sector, the financial services industry, to supply the insurance products that people need to guarantee themselves against the costs of care.’

The above graph shows that half of people who go into care homes die within a year, and three quarters die within three years. Less than 10 per cent of residents currently in homes will live for six years, long enough to take advantage of the cap, which comes into force in October 2023

The above graph shows life expectancy for people in a care home by whether they fund the care themselves (red line) or receive support (green line). It suggests that self-funders live slightly longer on average, compared to the other group. After 12 months in a home, around 30 per cent of people who are paying for their care home will have died, while 35 per cent of those supported by authorities will have passed away

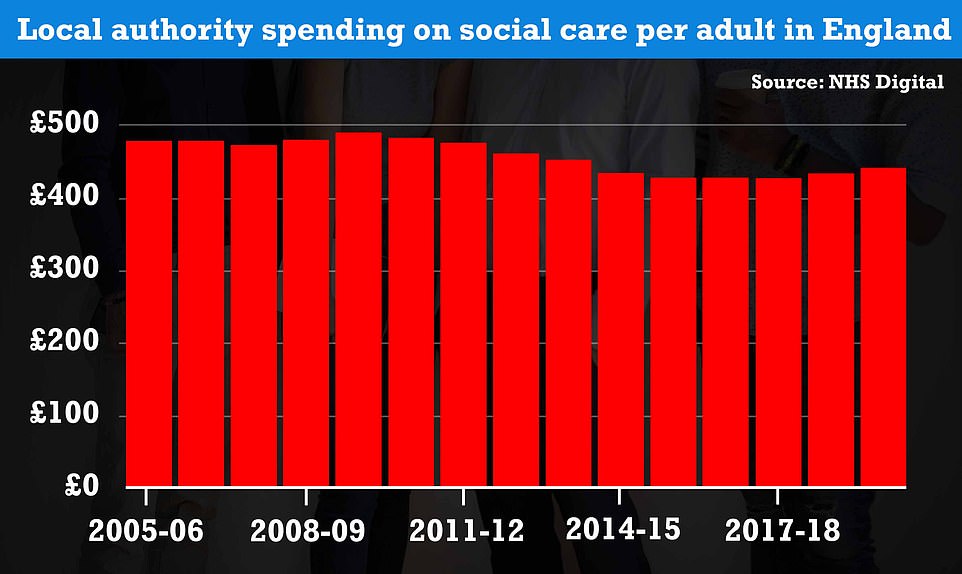

Spending on care will count towards Boris Johnson’s cap only if they are judged to need the support by the council. The above graph shows local authority spending on social care per adult in England from 2005 to 2019. Councils stuck to a strict budget, with spending varying between £400 and £500 per year over the 14-year period

The Prime Minister was pressed by the Labour leader over how his plan could meet the Conservative’s election pledge that nobody should be forced to sell their house to pay for care.

Sir Keir said during Prime Minister’s Questions: ‘Someonewith £186,000, if you include the value of their home — that is not untypicalacross the country in all of your constituencies — facing large costs becausethey have to go into care, will have to pay £86,000 under his plan.

‘That is before living costs.

‘Where does the Prime Minister think that they are going toget that £86,000 without selling their home?’

Mr Johnson responded: ‘This is the first time that the statehas actually come in to deal with the threat of these catastrophic costs,thereby enabling the private sector, the financial services industry, to supplythe insurance products that people need to guarantee themselves against thecosts of care.’

Asked whether his policy meant the Government wasencouraging people to take out insurance to avoid selling their home, MrJohnson’s official spokesman said: ‘ The private insurance market will now havethe ability, because of the certainty provided, to come forward.

Who qualifies for the new social care cap? When does it kick in? What does it cover?

Britons face higher national insurance tax from 2023 to cover health and social care costs.

One part of the plans involve no one in England having to pay more than £86,000 in their lifetime for social care.

The ‘cap on care’ covers help people need for certain activities, such as washing, dressing and eating.

Once someone has paid more than £86,000 for these services, the Government will take over paying their costs.

Ministers said the scheme means people will no longer face unpredictable or unlimited care costs and it tackles ‘persistent unfairness in the social care system’.

Once someone has reached the cap, local authorities will cover all of their eligible personal care costs.

However, the change does not kick in until October 2023, so any spending before this date does not count towards the cap.

Three in four current care home residents will not live that long and it would take them three years on average to hit the cap after it becomes active.

And once the new system comes into effect, anyone with more than £100,000 in assets – including property – will be responsible for paying all care costs until they have spent £86,000.

There is also a ‘floor’ for anyone with less than £20,000 in assets not required to contribute to costs.

Those with assets between £20,000 and £100,000 will have their care partly subsidised.

Not all payments a person makes related to their social care count towards this cap.

Any charges for ‘daily living costs’ in a care home – such accommodation, cleaning, food and bills – are not included.

So even after millions of Britons have spent £86,000 on their social care, they face paying monthly bills over £1,000 if they stay in a care home.

Authorities will partially fund the care of those who have between £20,000 and £100,000 in assets, while those with less than £20,000 will have all of their costs covered.

Local councils have the final say on what costs they are willing to pay.

For example, it might choose not to fully cover the costs of a more expensive care home.

If someone is receiving social care home visits, councils would pay for the hours they think someone needs at a set price, rather than the hours they used at the price they were charged.

People with over £100,000 in assets would pay for their care in full until they become eligible for free care through the cap, or their assets drop below £100,000.

Advertisement

‘It’s not for me to say what actions they will take.’

Mr Johnson is set to meet backbenchers tonight in a bid towin over potential rebels opposed to his manifesto-busting pledges ahead of acommons vote on Wednesday.

Half of people already in care homes do not live a year,while three quarters do not make it past three.

The Government already steps in to cover the cost of care ifsomeone’s assets fall below £23,250, including their savings and any propertythey own.

But it will not count someone’s property in their assesstsif a family member is still living in it.

The Government has insisted their cap on care means peoplewill no longer face unpredictable or unlimited care costs and tackles’persistent unfairness in the social care system’.

Once someone has reached the cap or had their assets fallbelow £23,250, local authorities will then step in to cover the costs of theircare.

But because the cap does not include daily ‘living costs’frail elderly people who reach it could still be left paying £1,000 a month forfood and accommodation.

On average, Britain’s have pension pots amount to £61,000.

Health Secretary Sajid Javid said the decision to abandonthe election pledge in order to provide £12 billion extra a year for the NHSand adult social care was the sign of a ‘responsible and serious government’.

But he acknowledged the extra money may not be enough toclear NHS waiting lists.

The Commons clashes came as experts continued to pore overthe details of Tuesday’s tax hike, based on a 1.25 percentage point increase inNational Insurance from April 2022.

The Resolution Foundation said the new system wasgenerationally unfair because the bulk of the money comes from working agepeople.

Although the levy will hit the earnings of working peopleabove retirement age from April 2023, the think tank said only one in sixpensioner households have earnings while two-thirds have private pension incomethat is not covered by the new tax.

The levy also excludes other sources of income such asrental income from buy-to-let homes.

The think tank said the £86,000 cap on care costs will be ofmost benefit to those in the more affluent south of England, as they see agreater share of their total assets protected by the cap and higher care costsmean they are also more likely to reach the limit and benefit from statesupport.

But poorer parts of England could benefit from the new meanstest, which sees care costs covered for those with assets under £20,000, andhelp available to those with up to £100,000.

The think tank said in the North East only 29 per cent ofindividuals aged over-70 have sufficient assets that they might receive nostate support, compared with almost half in the South West.

But the foundation warned that many people might still needto sell their home to pay for care if they do not have significant otherassets.

Resolution Foundation chief executive Torsten Bell said MrJohnson ‘has turned his back on low taxes in favour of an NHS-dominated state’.

He added: ‘The tax rises that will pay for a bigger NHS aregenerationally unfair, excluding rich retirees while prioritising wealthylandlords over their tenants.

‘And while the social care cap will prevent people being hitwith catastrophic costs, it will benefit southern households far more thanthose living in Red Wall seats.’

However, the Prime Minister’s official spokesman said:’Diseases like dementia affect families up and down the country.

‘This is an approach that provides certainty for people upand down the country, it is an approach which is progressive, which sees thosewho have more pay more.’

Health Secretary Sajid Javid earlier defended the package,telling the BBC: ‘These are the acts of a responsible and serious government.’

He said that ‘doggedly’ sticking to the manifesto commitmentcould have led to 13 million people being on NHS waiting lists in three years’time as a result of the backlog built up during the pandemic.

Asked if the money would clear the backlog, Mr Javid toldSky News: ‘No responsible health secretary can make that kind of guarantee.’

He added: ‘What I can be absolutely certain of is that thiswill massively reduce the waiting list from where it would otherwise havebeen.’

The measures announced on Tuesday will see taxes at theirhighest-ever sustained share of the economy, the Institute for Fiscal Studiessaid.

Will taxpayers get ANYTHING back for the NHS’s extra £10bn? Cash injection will be ‘gobbled up’ and there is NO chance of clearing waiting lists – which will get WORSE because of social distancing and pandemic (while unions are already demanding pay rises)

British taxpayers were warned today that Boris Johnson’s manifesto-busting £30billion NHS handout will be ‘gobbled up’ permanently by the health service, with waiting lists and delays here to stay.

The Prime Minister promised the extra £10billion a year to clear the mammoth backlog that has amassed during the pandemic, on top of £5.4billion cash boost announced for the NHS only a couple of days ago.

But the handout has been given to the NHS without any firm targets to meet, which has raised fears the money will simply be swallowed. NHS bosses have already complained the sum isn’t enough to clear the backlog.

Under proposals, half of the £10bn a year will be spent on social care in 2023 before the full amount is devoted to the care sector in 2025 and, in theory, the NHS reverts to its normal budget.

Critics have raised doubts about the plan, claiming that if the NHS goes on a recruitment spree to plug staffing gaps then a higher budget will become ‘baked into the system’.

Announcing the tax hike yesterday, Mr Johnson said the cash would go towards nine million more checks, scans and procedures by the end of 2025, as part of the ‘biggest catch-up programme in the NHS’s history’.

He promised to boost NHS capacity for routine operations by 30 per cent compared to pre-pandemic levels, hire 50,000 more nurses and open new surgical hubs to deliver extra operations and other procedures.

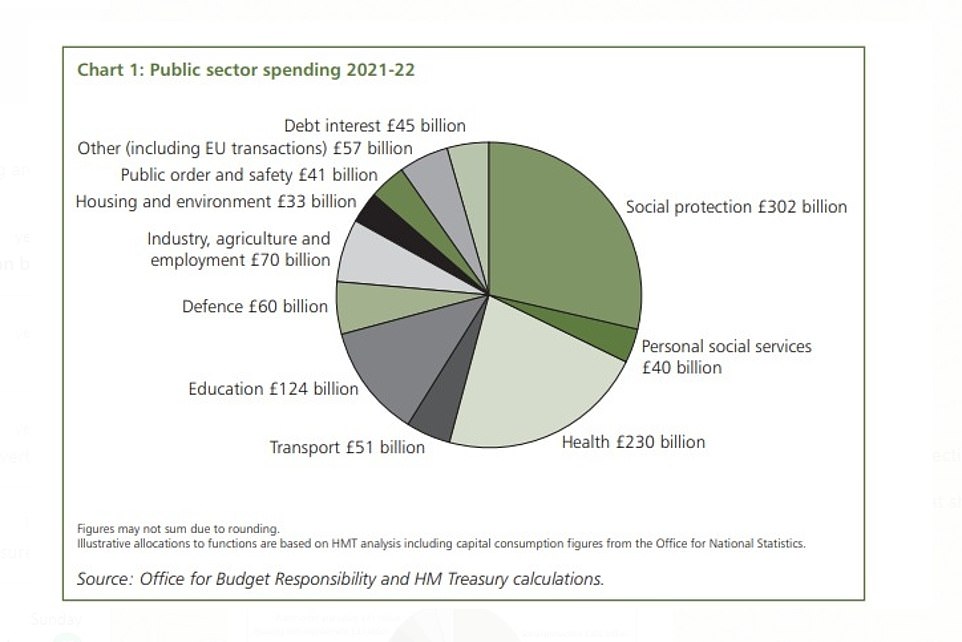

By 2025, around 40 per cent of all of day-to-day Government spending will go to the the Department of Health and Social Care, which funds the health service, according to the Resolution Foundation.

The conservative think-tank, the Institute for Economic Affairs (IEA), warned the cash boost will almost entirely be spent on hiring new staff and increasing wages, which will be hard to recoup after 2025.

Julian Jessop, an economics fellow at the IEA, said: ‘There is a risk that a temporary increase in spending on the NHS, to fix a temporary problem, becomes baked into the system, particularly via higher pay.

‘Without fundamental reform, the NHS is black hole which will swallow any money spent on it, leaving nothing extra for social care.’

The left-wing Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) said the funding is ‘nothing like enough to get through the backlog’, with the NHS alone needing £15billion per year to address the waiting list.

NHS England was already 38,952 nurses short at the end of June and it is not clear how quickly surgical hubs could take to set up or how they will be staffed.

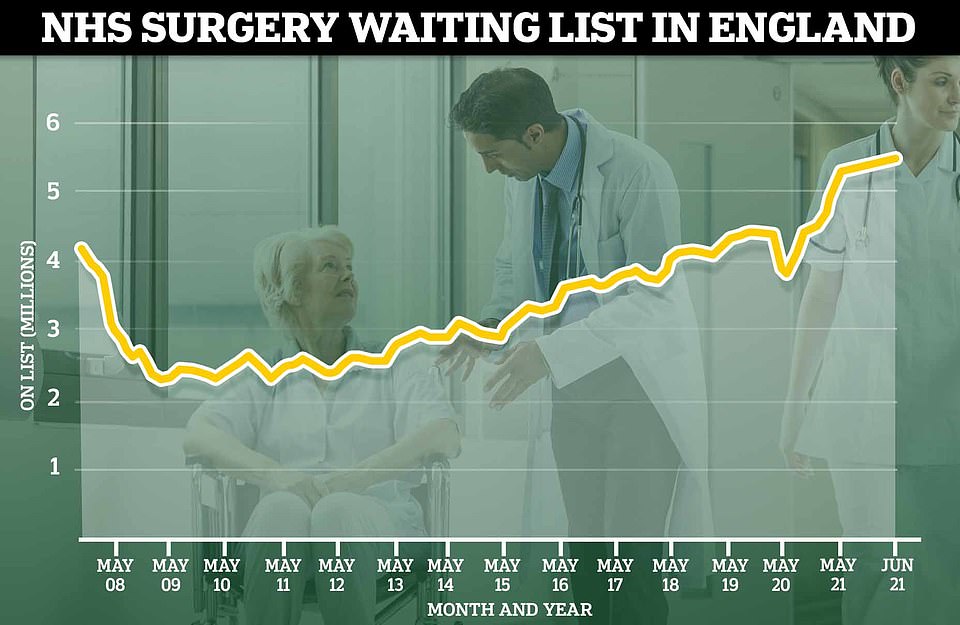

A record 5.5million people were on the waiting list for routine operations and treatments — such as hip and knee replacements — at the end of June and with data for July due out tomorrow, that figure is expected to further soar.

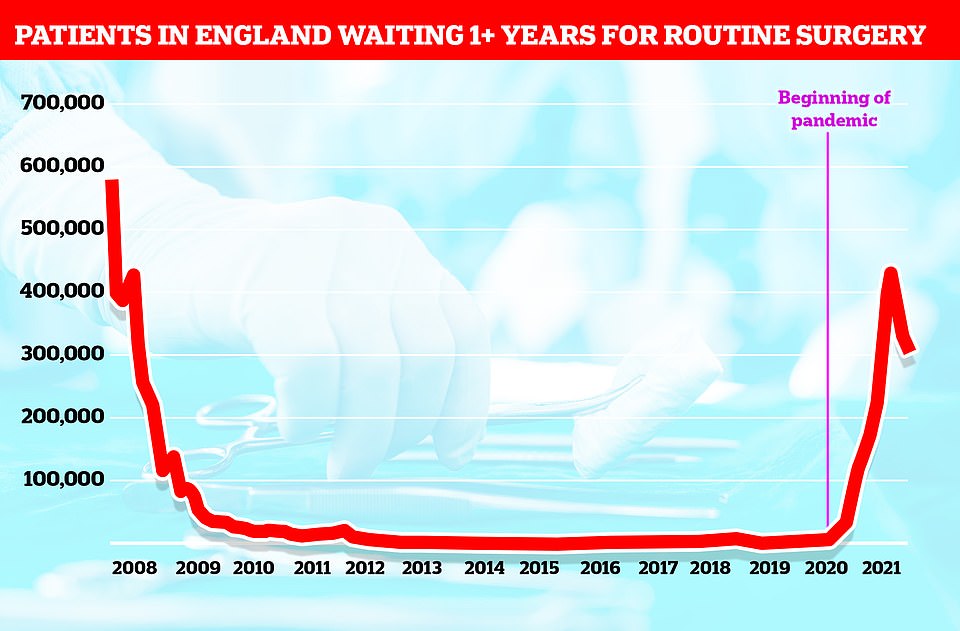

Some 5.5million patients in England were waiting for routine hospital treatment – such as joint replacement and cataract surgery – by the end of June, the highest figure recorded since records began in 2007. And 304,803 of those patients (5.6 per cent) had been waiting for more than one year. In August 2007, 578,682 people of the 4.2million-strong waiting list (13.8 per cent) had been waiting for more than 52 weeks, but this dropped drastically and remained relatively flat for nearly a decade. Some 1,613 patients had been waiting for more than a year when the Covid pandemic hit, which caused the figure to soar to a high of 436,127 in March. But those waiting 12 months or more began to drop in April as the country recovered from the second wave and the health service was able to begin working on the backlog

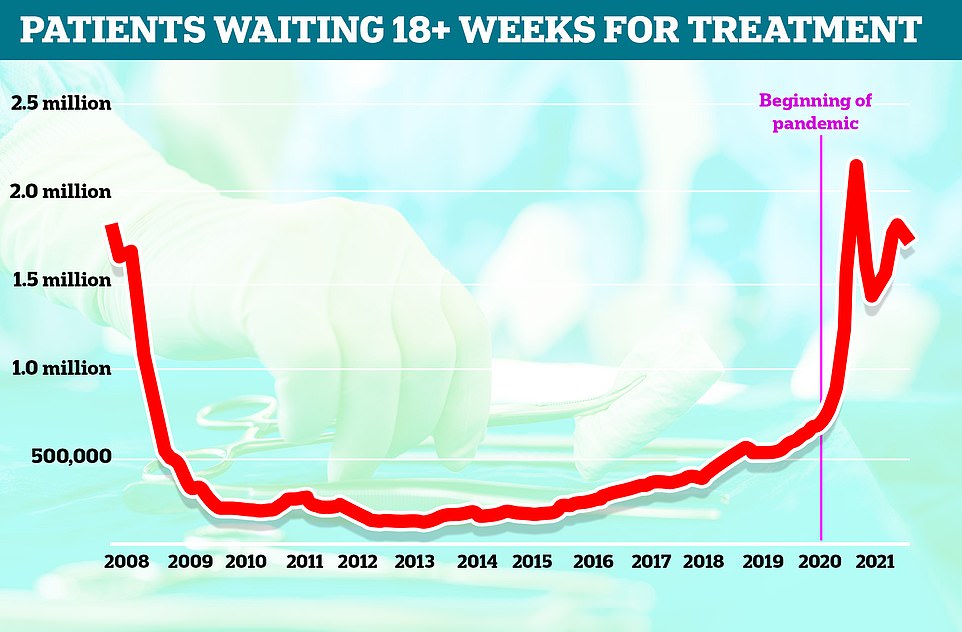

Patients forced to wait more than 18 weeks for routine surgery – the maximum time someone should wait under the NHS’s own rules – reached a record high of 2.1million last July. The figure then fell in 2020, but began to increase in March as health chiefs urged those who avoided seeking treatment during the pandemic to come forward. Before the Covid crisis, the largest number of patients forced to wait longer than 18 weeks was 1.7million in August 2007

The health and social care budget reached £212.1million in 2020, according to the King’s Fund. Some £148.7million of the sum was planned funding, while the remaining £63.4million was dished out to cope with the Covid crisis. For the second half of 2021 and first half of 2022, minister plan to spend a total of £181.4million on the health service, £22.4million of which will be linked to Covid recovery

The number of patients waiting for routine hospital treatment hit 5.5million in June, the highest figure since records began in 2007. And health chiefs have warned the backlog is going to get much worse before it gets better, with projections that it could soar up to 13million by the end of the year if no action is taken

NHS England waiting list could soar to FOURTEEN MILLION by autumn 2022 and keep growing, says think tank

The NHS waiting list in England could soar to 14 million by the autumn of next year and keep growing, an influential think tank has warned.

If millions of patients who missed out on care during the pandemic seek medical attention, then the number joining the waiting list could outstrip the number being treated, the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) said in a report last month.

Last month, Health Secretary Sajid Javid warned that NHS waiting lists in England could rocket to 13 million.

The IFS warned the number could top this figure if most of the near seven million so-called ‘missing’ patients return to the health service in the next year.

It said: ‘Under this scenario, waiting lists would soar to 14 million by the autumn of 2022 and then continue to climb, as the number joining the waiting list exceeds the number being treated.’

The IFS said it was unlikely all patients will return as some will have died and others might have had private treatment or chosen to live with their illnesses.

Advertisement

The backlog was forecast to hit 13million by December without any action, with 7million patients expected to come forward who put off seeking treatment during the pandemic.

The health service also faces challenges from a surge of Covid and flu cases expected this winter and social distancing still being enforced in hospitals. Hospitals are aiming to keep two metres between patient beds and staff, which requires more space and can reduce capacity.

It has also been told to prepare for mammoth vaccination programmes for Covid booster jabs and for all over-12s, as well as the country’s biggest-ever flu jab rollout, which is expected to reach 35million people.

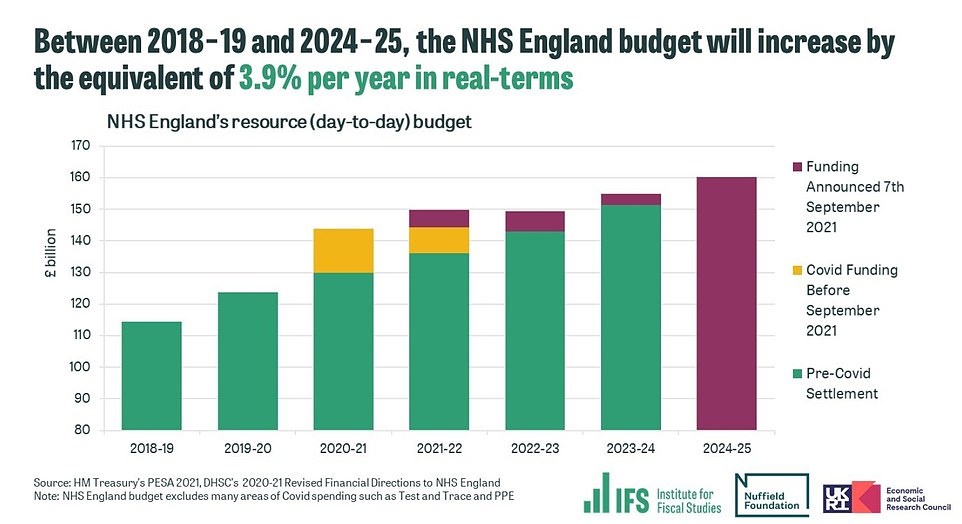

The Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS) said the the Government has historically topped up NHS spending, so the ‘temporary’ increase in NHS funding ‘could end up permanently swallowing up the money raised by the tax increase’.

From 1982 to the start of the pandemic, proposed NHS spending plans involved increasing its annual budget by an average of 2.7 per cent, according to the IFS. But annual spending actually grew by 4.1 per cent on average, as minister topped up the amount.

If ‘history repeats itself’, top-ups to the funding announced this week for the NHS could ‘easily eat into the amount available for social care’, the IFS said.

Professor Len Shackleton, editorial and research fellow at the IEA, said that lots of the extra funding would inevitably be gobbled up by wage increases.

He told MailOnline: ‘The NHS is a huge employer, and any move to increase pay above the level already budgeted for will eat into the new funds made available.

‘And, given that the plan to clear the backlog involves recruiting substantial numbers of extra staff while having many existing staff work longer hours, it is almost inevitable that pay will be increased.

‘A 1.5 per cent pay increase would cost about £1 billion. If NHS costs do escalate, improvements to social care provision will be slow and underfunded.

‘We should not assume that this clever political fix has solved the longer-term problems of health and social care provision.’

And job adverts online reveal that the NHS is hiring 42 new chief executives across the country, who will receive an average salary of £223,261. One in six of the new hires will be paid £270,000 – more than the Prime Minister.

Rachel Harrison, national officer at the trade union GMB, said the funding should be used to give NHS staff a retrospective 15 per cent pay rise, which would use up all of £10billion funding, according to Professor Shackleton’s estimates.

She said: ‘Morale among NHS staff is at a low ebb. They’ve faced ten years of real terms pay cuts and underfunding – leaving the health service with a massive 75,000 staffing black hole.

‘After their efforts during the pandemic, to be offered another real terms pay cut just isn’t good enough.

‘Any new NHS funding that doesn’t go towards giving staff a proper pay rise spectacularly misses the point.

‘GMB is calling for a restorative 15 per cent increase to make up for a decade of slashed pay under the Conservatives.’

And Richard Murray, chief executive of the King’s Fund think-tank, said wages are likely to go up, as medics have to work longer due to staff shortages.

He told MailOnline: ‘If you put a lot of money into the NHS very quickly that they weren’t ready for – which is true in this case – they have to find staff.

‘You can’t invent extra doctors and nurses, the workforce is what it is.

‘This means you risk two routes – one is paying more people for overtime and bringing in expensive agency workers. So paying higher rates for longer hours.

‘You can also try to persuade existing staff not to drop out early or retire. Some of that can show up in pay, but it can also be in areas like training and career development to try and keep people longer than they would otherwise plan to stay.’

Mr Murray predicted some of the money could go on diagnostic equipment and extending opening hours at operating theatres, or perhaps even on new hospital buildings.

‘Britain has very few MRI and CT scanners. The Government has also promised a large hospital building programme too.

‘One thing to note is that the money that has been announced by the government is revenue spending and things like large scanners are taken from capital spending.

‘So either in the spending review we’ll see another slug of money appearing for capital spending or some of the money will be moved across from revenue into capital.

‘They said by the end of the period they want a 30 per cent increase in elective activity.

‘It’s hard to build completely new things so I think you’ll see them trying to draw on independent sector capacity.

The health service’s budget in 2024/25 will be nearly four per cent higher than it was in 2018/19, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies. It is projected to reach £160billion, according to the funding that was announced yesterday

‘And an attempt to make sure they’re using operating theatre and scanners to their full capacity and ensuring appointments aren’t being cancelled and these areas are being left empty.

‘Hips and knee replacements are huge areas in the waiting lists, so they’ll be an emphasis on giving more support afterwards.’

Mr Murray said hospital opening hours could be extended in order to reach the government’s target of boosting the number of elective procedures by 30 per cent, but it would be a ‘balancing act’ not to alienate staff with longer hours.

‘Hospitals could be run for longer hours, but you need the staff to do it,’ he said. ‘The risk is that if staffing hours aren’t going up then you’ll see them working longer hours.

‘It’s a fine path to tread not to get people to work so hard that they want to leave.

‘The government will be looking at what can be done with general practice, because quite a few patients are stressed about this and some dislike the digital route.

‘I’d expect to ministers see how they can use other staff like community pharmacists to try to ease the pressure on general practice.

‘Lengthening surgery opening hours produces the same risk of alienating an already frustrated workforce by making them work for longer.’

And adding to the concerns that extra cash will not be enough to cut the waiting list, NHS Confederation and NHS Providers, which represent hospitals and health service organisations, said the funding falls £3.5billion short of what is needed due to the ‘seismic impact’ of Covid and rising demand on the NHS.

Ministers should ‘manage public expectations about how long it will take to deal with the care backlog’, because the funding limits NHS ability to tackle the shortfalls in treatment and care, they said.

The funding does not go ‘nearly far enough’, which leaves health and care leads with an ‘impossible set of choices about where and how to prioritise care for patients’, they added.

Chris Thomas, IPPR senior research fellow, said the NHS will be ‘deeply worried’ about its long-term financial position.

He said: ‘The funding announced is nothing like enough to get through the backlog and deliver the transformation needed to build back better.

‘This will have severe health and economic consequences for years to come, while also leaving the country fundamentally unprepared for future health shocks.’

Estimates have put the cost of the Covid backlog at £10billion per year, but IPPR said the NHS would need an annual funding boost of £15billion to treat those on the list, because its ‘performance and resilience were at record lows’ before the pandemic, the IPPR said.

Dr Susan Crossland, president of the Society for Acute Medicine, said the additional funds for the NHS along ‘will barely scratch the surface after years of neglect’.

She said: ‘Patients, staff and the wider public will not be convinced by figures or that this Government has a real understanding of how to resolve the NHS and social care crises given it has failed to get the basics right – and no injection of money will help our current exhausted workforce.’

The ‘basics’ include renovating ageing hospitals, retaining and recruiting staff, increasing bed capacity and sorting out social care, Dr Crossland added.

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-9969685/Millions-pay-tens-thousands-care-Boris-new-social-care-cap.html