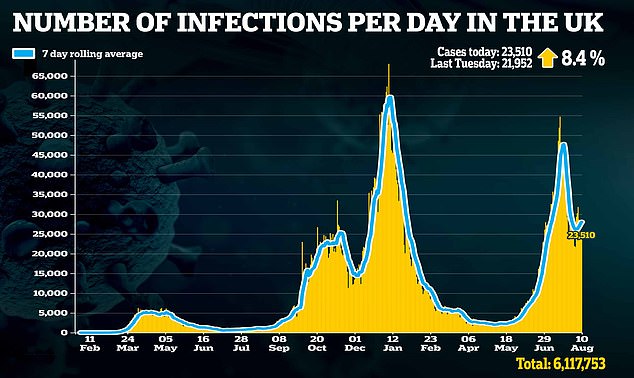

Professor Adam Finn, who sits on the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) — the Government on Covid vaccine policy, says the number of serious cases among young people has been increasing in recent weeks

The panel advising the Government on Covid vaccine policy U-turned to allow over-16s to have a jab because of a rise in the number of infected children getting seriously ill, one of the experts claimed today.

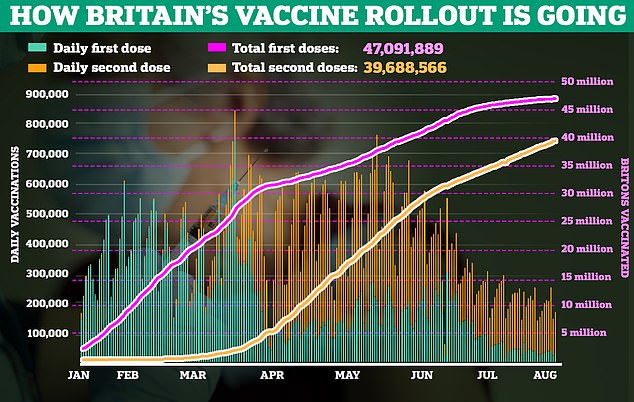

Ministers announced the rollout would be extended to 16- and 17-year-olds last week, after the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) changed its tune on the policy.

Previously, health chiefs were against inoculating teenagers amid fears over myocarditis — a rare heart condition being linked to Pfizer and Moderna’s vaccines.

But Professor Adam Finn, who sits on the JCVI, said the number of serious cases among young people in recent weeks merited a change in approach.

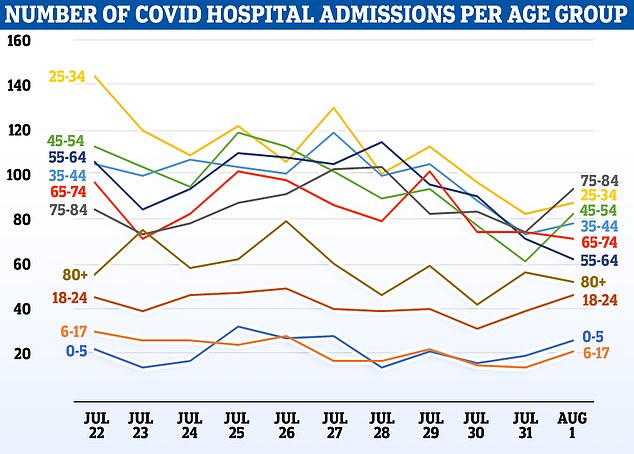

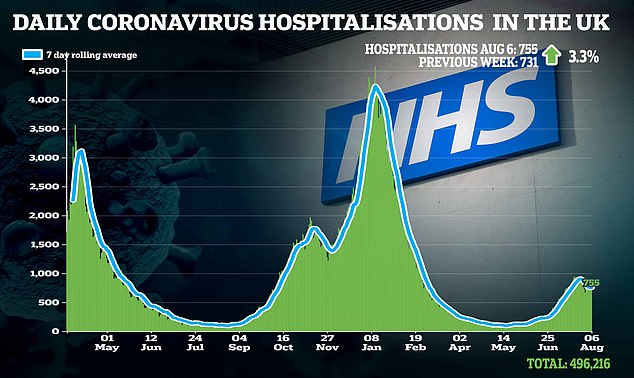

NHS data shows around 20 Covid-infected children aged between six and 17 are being admitted to hospital every day currently.

For comparison, the rate was in single figures until the start of July, when the third wave began to spiral rapidly. There were two days in May where no youngsters were hospitalised.

The tiny numbers of children who become seriously ill is the main argument used by critics of No10’s decision to expand the roll-out to youngsters.

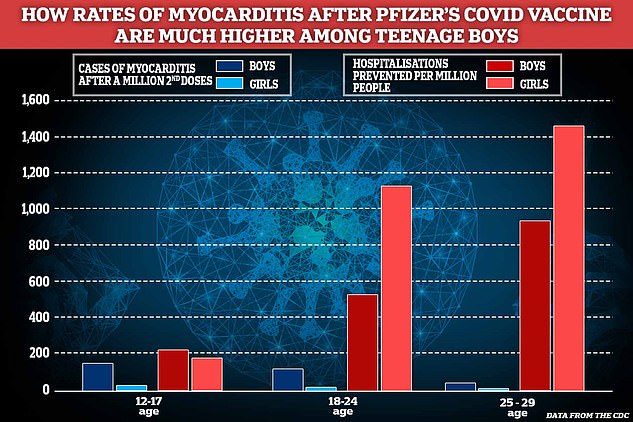

Data also suggests around one in 15,000 teenage boys given Pfizer’s jab will develop myocarditis — which can lead to heart failure.

It has raised concerns about the risk-benefit ratio for children, especially boys, who may be up to 14 times more likely to be struck down with the complication.

But other scientists agree with the UK’s move to vaccinate children, saying cases of the condition appear to usually be mild.

Any increase in prevalence tips the risk-benefit balance in favour of jabs because the dangers posed by Covid are skewed higher.

Professor Finn, a paediatrician at Bristol University, said while most young people will only have the virus in a mild form, the vaccines will be effective at preventing serious cases.

NHS data shows around 20 Covid-infected children aged between six and 17 are being admitted to hospital every day currently

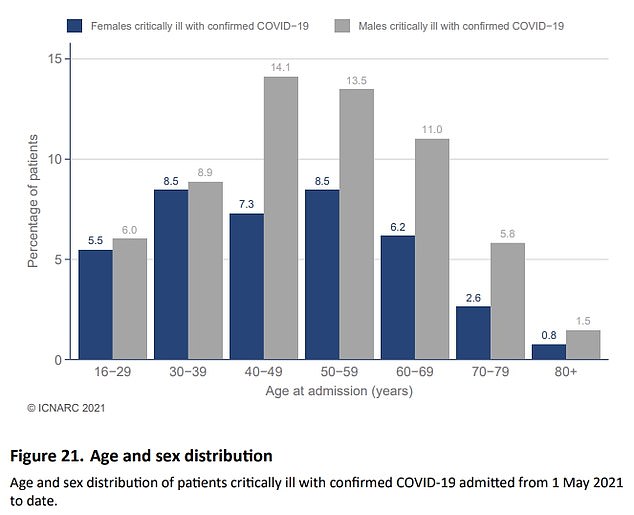

Since May, men aged 16 to 29 have made up 5.5 per cent of all male hospitalisations, while women in the age group have made up six per cent, according to data from the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre (ICNARC)

Teenage boys are 14 TIMES more likely to suffer rare heart complication from Pfizer’s Covid jab, study warns amid growing calls for No10 to rethink plan to inoculate 16 and 17 year olds

Pfizer’s Covid vaccine may pose more of a risk to boys, a study claimed today amid growing calls for No10 to rethink plans to dish out jabs to children.

New research has suggested boys are 14 times more likely to be struck down with a rare heart complication called myocarditis.

The data, from the US, will likely fuel an already fierce debate over Britain’s decision to press ahead with inoculating all 16 and 17-year-olds.

Last week, the Government’s advisory panel ruled older teenagers should be given their first dose. Ministers plan to invite them before they head back to schools and colleges in September.

But health officials have yet to make concrete plans for children to get top-ups. They want to wait for more safety data about myocarditis before pressing ahead.

Real-world data from the US, which has been vaccinating children for months, have shown teenage boys to be at a higher risk.

It prompted one member of the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation, which green-lighted the move to jab children, to admit different advice for boys was ‘theoretically on the cards’.

There is already precedent for just giving vaccinating just one gender, with the HPV jab offered only to girls until 2018.

Advertisement

Professor Finn told BBC Breakfast: ‘We’re going cautiously down through the ages now into childhood and it was clear that the number of cases and the number of young people in the age group — 16, 17 — that were getting seriously ill merited going forward with giving them just a first dose.’

He said the JCVI would advise ‘when and what’ the second dose for that age group would be after assessing more data.

He added: ‘Most young people who get this virus get it mildly or even without any symptoms at all.

‘But we are seeing cases in hospital even into this age group — we’ve had a couple of 17-year-olds here in Bristol admitted and needing intensive care over the course of the last four to six weeks — and so we are beginning to see a small number of serious cases.

‘What we know for sure is that these vaccines are very effective at preventing those kind of serious cases from occurring.’

NHS England said nearly 16,000 people in the 16- to 17-year-old age group have already received their vaccine over the weekend, just days after JCVI guidance was updated.

Extending the jabs rollout further down to the 12- to 15-year-old age group has not been ruled out.

Professor Danny Altmann, an Imperial College London immunologist, said he thinks doing so would be ‘a good thing’.

He told Times Radio the more unvaccinated people there are, the more lungs there are ‘for virus to percolate in, therefore it’s got to be a good thing to be vaccinating more children down through the age range’.

He said children who have the virus but do not have symptoms are ‘as dangerous to the spread as anybody else’.

He said: ‘From a medical scientific point of view, I’d say there’s nothing special about the virus in their lungs that can’t transmit through to their families, through to their schoolteachers, through to their colleagues.’

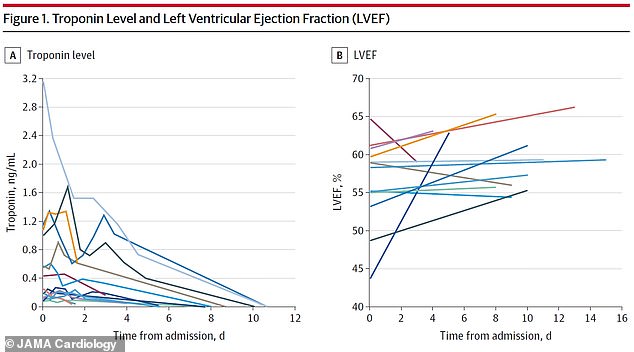

Research yesterday, published in JAMA Cardiology, suggested boys are 14 times more likely to be struck down with the heart complication after Pfizer’s jab — which will be given to British children.

The study was based on an analysis of just 15 children. Only one was a girl.

The findings echoed Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data, which suggests the risk is up to nine times higher among teenage boys.

All 15 experienced chest pain, which started a couple of days after being vaccinated and lasted for up to nine days.

None were struck down with a serious bout of myocarditis or required intensive care. All were discharged within five days.

It comes after Sir Andrew Pollard, the JCVI’s chair, said pupils who are not unwell should not have to isolate after being in contact with a Covid case in the classroom.

Sir Andrew, who helped to create the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine and is a professor of paediatric infection at the University of Oxford, said that as long as children who are contacts are not ill, they should continue to be in school getting their education.

He told the All Party Parliamentary Group on Coronavirus on Tuesday: ‘Given that children have relatively mild infection compared to adults, apart from the exceptions who are largely going to be vaccinated in the current programme anyway, we probably should be moving to a situation where we’re clinically-driven.

‘If someone is unwell, they should be tested, but for those contacts in the classroom, if they’re not unwell then it makes sense for them to be in school and being educated.’

The latest schools infection survey from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) showed that 0.27 per cent of primary school pupils, 0.42 per cent of secondary school pupils, and 0.27 per cent of secondary school staff tested positive for coronavirus on the day of testing in June.

Statisticians said the survey of 141 schools in England showed prevalence of infection among pupils sampled in school was consistently lower than prevalence among children in the wider community.

The patients arrived at the hospital with elevated troponin levels, an indicator of heart injury – but their hearts recovered significantly during short hospital stays

Public Health England (PHE), which co-leads the study, said the latest results confirm ‘schools are not hubs on infection’.

Dr Shamez Ladhani, consultant paediatrician at PHE and study lead, said: ‘The latest results show that infection and antibody positivity rates of children in school did not exceed those of the community.

‘This is reassuring and confirms that schools are not hubs of infection.

‘Keeping community infection rates low remains critical for keeping children safe and schools open safely.’

Professor Mark Woolhouse, an epidemiologist at the University of Edinburgh, said there is now a ‘wealth of evidence from around the world that schools are not the main driver of Covid epidemics’.

He said the latest ONS survey ‘does not raise any immediate concerns about the re-opening of schools after the summer holidays’ and added that the future inquiry into coronavirus should consider whether there was ever any need to close schools, saying he believes the epidemiological evidence suggests the answer may be no.

From August 16, children under the age of 18 will no longer be required to self-isolate if they are contacted by NHS Test and Trace as a close contact of a positive Covid case.

Instead they will be informed they have been in close contact with a positive case and advised to take a PCR test.

Guidance issued at the end of term states that schools no longer need to perform contact tracing after being notified of a positive case.

Close contacts will now be identified through the Test and Trace programme.

Previously, children were required to isolate for 10 days if another pupil in their bubble — which could be an entire year group — tested positive for Covid.

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-9883405/Covid-19-UK-Expert-says-JCVI-U-turned-jabs-teens-string-cases.html