Mothers who are at risk of premature birth could be identified just 10 weeks into their pregnancy by using a swab to measure bacteria, a study has suggested.

A total of 60,000 babies are born prematurely in the UK every year, equating to around eight in every 100 births.

It is the leading cause of death in newborns and those who survive are vulnerable to lifelong heath issues.

Researchers have uncovered specific bacteria and chemicals in expectant mother’s cervixes which put them at risk of infections and inflammation – which can lead to premature birth.

They hope their finding will allow new tests and treatments to be developed that can be administered much earlier than current tests.

A total of 60,000 babies are born prematurely in the UK every year, equating to around eight in every 100 births (file)

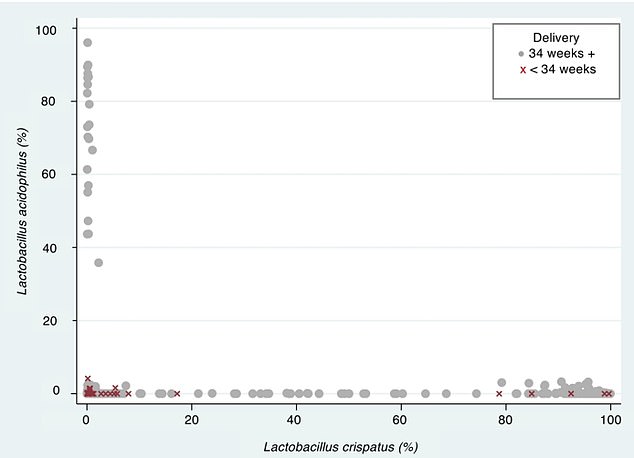

Researchers found that women who less than 20 per cent of a bacteria called Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus acidophilus were more likely to give birth earlier. The red crosses represent women who gave birth early, the majority of which had less than 20 per cent of the bacteria in their samples

The NHS currently determines if a woman is at risk of giving birth early based on whether they have done so previously, if their cervix has been damaged during surgery or if their cervix is short.

A woman’s cervix usually lengthens during pregnancy to protect the baby, before shortening and softening during for labour and birth.

How common are premature births?

Around eight per 100 babies are born before 37 weeks of pregnancy.

This means around eight per cent of births in the UK are preterm, equalling around 60,000 babies a year.

Of these births, five per cent were extremely preterm – meaning they happened sooner than 28 weeks.

Around one in 10 were very preterm, which means the mother gave birth between week 28 and 32 of pregnancy.

Meanwhile, the majority were moderately premature, meaning the baby was born between 32 and 37 weeks.

Around 95 per cent of babies born after 31 weeks in the UK survive, but the survival rate drops the earlier that the baby is born.

The earlier a baby is born, the higher the risk of it having health problems.

One in 10 of preterm babies will have a permanent disability, such as lung disease, cerebral palsy, blindness or deafness.

And around half of those born before 26 weeks will have a disability.

The risk of giving birth prematurely is highest for black Caribbean women (10 per cent) and lowest for white women (six per cent).

The NHS can determine if a woman is at risk of giving birth early based on whether they have done so previously, if their cervix has been damaged during surgery or if their cervix is short.

But in some cases, pre-term labour is planned because it is safer for the baby to be born sooner, such as if the mother has a health condition.

Source: Tommy’s

Advertisement

But if a woman suffers from infection or inflammation during pregnancy, it can weaken the cervix and cause it to shorten too early, putting them at risk of premature birth.

There are currently only two treatments used to prevent premature birth.

One sees a tablet of hormone medicine inserted into the vagina while the other involves an operation to put a stitch in the cervix within the first 24 weeks of pregnancy to help support it.

But Tommy’s, a pregnancy charity that helped fund the research, said the current standard tests for premature birth are most accurate late in pregnancy when there’s less doctors can do to intervene.

Researchers looked at data from four UK hospitals on 346 mothers, 60 of whom gave birth prematurely.

They analysed bacteria taken from swabs at 10-15 weeks pregnant, and again at 16-23 weeks.

This was checked against cervical length measurements – the current NHS assessment for premature birth risk – and followed up to see who gave birth early.

A combination of metabolites – glucose, aspartate and calcium – and bacteria was linked to birth at or before 34 weeks.

Meanwhile seven different metabolites were associated with birth at or before 37 weeks.

These links were equally significant in the first and second trimester, meaning those at risk of premature birth could be accurately identified much earlier in pregnancy than current tests allow.

This means these women could benefit from medical or surgical treatments that aren’t possible in late pregnancy.

Professor Andrew Shennan OBE, an expert in obstetrics at King’s College London, who authored the study and runs the Tommy’s Preterm Surveillance Clinic at St Thomas’ Hospital, said: ‘Premature birth is very hard to predict, so doctors have to err on the side of caution and mothers deemed to be at risk often don’t actually have their babies early, putting undue strain on everyone involved.

‘My team has developed preterm birth prediction tools that are very accurate later in pregnancy, like fetal fibronectin tests — but at that stage, you can only manage the risks, not stop it from happening.

‘The sooner we can find out who’s at risk, the more we can do to keep mothers and babies safe.’

Professor Rachel Tribe, an expert in maternal and perinatal sciences at King’s College London, who was lead academic on the study, said: ‘With so many factors in play, it’s unlikely that testing for the same single bacteria species will predict preterm birth in every mother, but we now have a panel of bacteria and metabolites that could be useful.

‘In particular, tests during early pregnancy for Lactobacillus crispatus and Lactobacillus acidophilus could provide reassurance to mothers who would otherwise be unduly worried, and help those who need it get specialist care as soon as possible.

‘After five years of work on this study, we’re delighted to have this greater understanding of how the vaginal environment can influence preterm birth risk.’

Jane Brewin, chief executive at Tommy’s, said: ‘With 60,000 babies born prematurely each year in the UK, there’s a real and urgent need for better ways to predict and prevent preterm birth.

‘This new study has not only uncovered warning signs that could be used to develop new tests, but also a possible treatment which could make pregnancy safer for the most vulnerable, so this new avenue of research has really exciting potential for clinical practice.’

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-9918875/Premature-births-predicted-early-10-weeks-pregnancy-study-suggests.html