Children in England’s most deprived areas are nearly twice as likely to be short than those from affluent neighbourhoods, a study has found.

Researchers at Queen Mary University London examined the height of seven million four and five-year-olds across the country.

More than 2.6 per cent of youngsters are short in the poorest areas, compared to around just 1.4 per cent in the wealthiest regions.

They warned those from the poorest parts of the country are ‘failing to reach their full growth potential’ at a critical time in their development.

Reception age children had an average height of three-and-a-half foot (109.6cm) across different ages and genders, but the researchers didn’t specify exactly what height was too short, due to the complex algorithm they used.

There are ‘striking’ differences based on how wealthy an area youngsters lived in and a ‘clear North-South divide’ in the prevalence of children who are short.

Yorkshire and the Humber, the North West and North East had the highest rates of short children, while the figures were lowest in London, the South East and South West.

The researchers said more studies are needed to find out why children from poorer areas are shorter, but said higher infection rates, pollution, a poor diet and vitamin D deficiency may be factors.

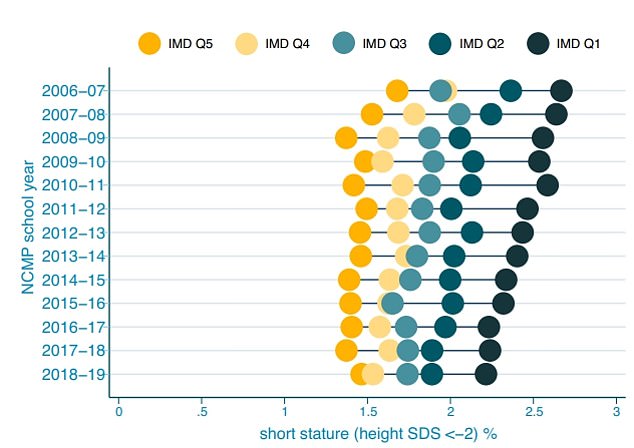

The graph shows the proportion of children who are short per year in relation to how deprived the area they live in is. Some 2.56 per cent of children in the most deprived areas (IMD Q1, indicated by black dots) were small, while the rate dropped to just 1.38 per cent in the least deprived areas (IMD Q5, indicated by the orange dots)

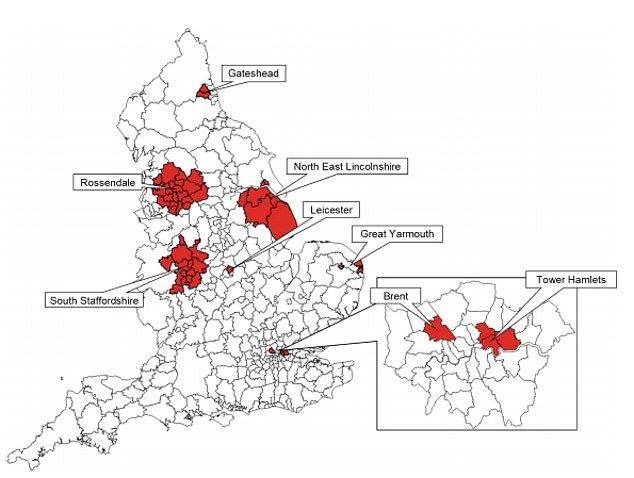

The map shows parts of the country with the highest proportion of children that are short for their age, based on data from seven million children between 2006 and 2019. Overall, the highest proportion of short children was found in Leicester (3.1 per cent) followed by Great Yarmouth in Norwich (2.8 per cent), Brent (2.8 per cent) and Tower Hamlets in London (2.6 per cent). Rates were also high in Rossendale (2.5 per cent), North East Lincolnshire (2.5 per cent) and South Staffordshire (2.4 per cent)

The study, which was published in the journal PLOS Medicine, examined a database containing details of 7.1million children.

The data was collected between 2006 and 2019 as part of the National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP).

The programme collects children’s height and weight to work out their body mass index and assess their health.

But the team of researchers said NCMP focuses on BMI and does not routinely identify short children to their families or GPs, despite height being a marker of underlying health conditions or poor nutrition.

Which children were the most likely to be short?

The study by researchers at Queen Mary University London examined a database containing details of 7.1million children in England.

The data was collected between 2006 and 2019 as part of the National Child Measurement Programme, which collects youngsters’ height and weight to work out their BMI and assess their health.

The researchers spotted ‘striking’ disparities in the proportion of short children depending on which part of the country they lived in, how deprived the area was and ethnicity.

Region

Yorkshire and the Humber: 2.18%

North West: 2.14%

North East: 2.12%

East Midlands: 2.08%

West Midlands: 2.05%

East of England: 1.89%

South West: 1.86%

South East: 1.74%

London: 1.57%

Ethnicity

Other: 2.57%

Indian: 2.52%

Pakistani and Bangladeshi: 2.18%

White: 1.95%

Mixed: 1.58%

Black African and Caribbean: 0.64%

Deprivation Level

1 (Most deprived): 2.56%

2: 2.24%

3: 2.09%

4: 2%

5: 1.88%

6: 1.75%

7: 1.70%

8: 1.62%

9: 1.51%

10 (Least deprived): 1.38%

Advertisement

Researchers found that 1.93 per cent of children across England were short for their age, and mapped the location of these youngsters across the country.

But the rates of short children was not evenly spread.

Some 2.56 per cent of youngsters are short in the poorest areas, compared to just 1.38 per cent in the wealthiest regions.

The proportion of short children increased in relation to how poor an area was.

And there are ‘hotspots’ of short children in England, which were mostly concentrated in the North and Midlands.

The prevalence of short children was highest in Yorkshire and the Humber (2.18 per cent) and the lowest in London 1.57 per cent).

And within local authorities, the proportion of children with below average height varied from 0.97 per cent in Richmond upon Thames in London to 3.92 per cent in Blackburn with Darwen in the North West.

This four-fold differences translates into an extra 2,950 short children per 100,000 children starting school in the worst-off areas.

‘Many of these children may in fact be particularly disadvantaged, unhealthy, and failing to thrive,’ the researchers wrote.

Height was also linked with ethnicity. White children were three times more likely to be short (1.95 per cent) compared to Black African and Caribbean children, who were the least likely to be short (0.64 per cent).

And overall, Indian children and those classed as an ‘other’ ethic group were most likely to be smaller (2.52 per cent and 2.57 per cent).

Additionally, girls were more likely to be short (2.09 per cent) than boys (1.77 per cent). Researchers found that the prevalence of short children declined over time.

In the cohort of children examined in 2006 to 2010, some 2.03 per cent were below average height, but between 2016 and 2019, just 1.82 per cent were smaller than expected.

But despite the drop, the experts said differences between children based on disparity levels was persistent.

Joanna Orr, a researcher at Queen Mary and first author of the study, said: ‘Whilst the average prevalence of short stature across England was in line with what we’d expect, the regional differences we see are striking, and there’s a clear North-South Divide.

‘Our findings show that where a child is born and the environment in which they grow up have an impact on their height at a young age and suggest further investigation is needed into why children from poorer areas of England are shorter.’

Professor Andrew Prendergast, a paediatrician at the university, said: ‘Currently most UK public health programmes focus on body mass index as the main indicator of health so even though the heights of school children in England are being measured as part of this National Programme, children with short stature are not currently systematically being highlighted to their families or GPs for action.

‘Height could be a marker for other vulnerabilities, such as underlying health conditions or poor nutrition, so nationwide screening programmes could provide an opportunity to identify children who are short for their age and intervene early.’

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-10037393/Children-living-Englands-deprived-areas-nearly-TWICE-likely-short.html