GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

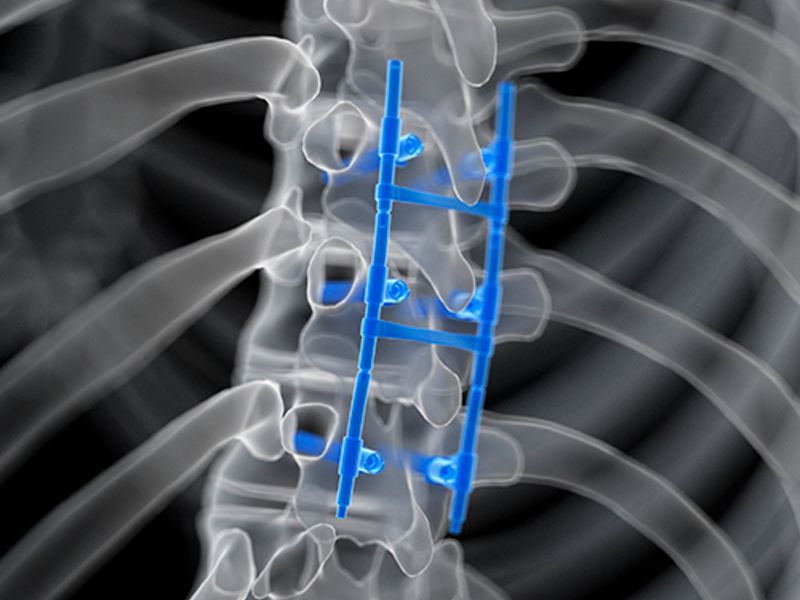

In most orthopedic departments, there’s a big chance spinal fusions are one of the most common procedures, and also one of the most costly and lucrative. The surgery can be great for people who suffer traumatic injuries, such as from car crashes, or who have congenital disorders or even arthritis in the back with some slippage of vertebrae in the spine. But the procedure is also potentially one of the most overused and unnecessary, and surgeons often recommend it for a host of conditions despite unclear evidence of its effectiveness. The lack of rigorous clinical trial evidence is apparent in a recent study, which raises questions about why surgeons are cutting into so many backs without clearly knowing whether it works, and about a healthcare industry that relies on expensive medical devices that don’t undergo the same stringent regulatory reviews as prescription drugs. For hospital administrators, expensive procedures and devices used by doctors may seem par for the course in the U.S. healthcare system. But the rising frequency and cost of spinal fusions suggest a closer look at orthopedic departments may be needed. Spinal fusions can, on average, cost between $60,000 to $110,000.

Download Modern Healthcare’s app to stay informed when industry news breaks. A British Medical Journal review of randomized controlled clinical trials on several elective orthopedic surgeries found little evidence to support spinal fusions on patients with degenerative disk disease. There was also little evidence to justify surgery over nonoperative treatments for five other orthopedic procedures, including rotator cuff repairs. And spinal fusion, even beyond the one indication the study looked at, is controversial. There’s hazy evidence, at best, that it should be used to treat a condition called spinal stenosis, which is a severe form of arthritis that mainly affects older people. In the absence of trial data on the effectiveness of spinal fusions for many conditions, and of the medical devices used in the procedure, surgeons are left to rely on sales pitches from self-interested devicemakers—often the same companies that have financial relationships with those physicians—as well as observational data that is not as robust. Surgical treatment usually has two components: decompression and spinal fusion. For the former, physicians open patients’ backs and cut out arthritic bone that pinches the nerves that run from the back to the leg. For the latter, surgeons use a bone graft to weld vertebrae together, often with a medical device to stabilize the area. “That procedure is probably way overused and studies say that in patients who have spinal stenosis itself, it’s more expensive and riskier, with more complications. And researchers have shown that despite decompression alone being safer and with similar outcomes, fusion is increasing” said Dr. Steven Atlas, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.More surgeries Spinal fusions are risky, in part because patients can wind up with worse problems than when they started. That’s especially concerning for patients with conditions for which the surgery may not even be advisable. “Over time, fusion—where you’re fusing two bones together and there’s no movement between the bones and there used to be movement—there’s evidence that you increase arthritic changes above and below where the fusion was,” Atlas said. That can increase stress at the segments below and above the vertebrae, leading to a domino effect in which patients need more fusions to alleviate pain. But despite the available evidence, spinal fusions have proliferated over time. Lumbar spine fusions increased by 142% between 1998 and 2008, according to a study by the Spine Research Foundation. A review of Medicare claims shows that a more complicated version of the surgery involving more surfaces of the vertebrae, increased 38% from 2004 to 2007, indicating a shift toward more complex and costly operations. By 2015, more than 40% of spinal fusions performed in the U.S. were for indications with less evidence of clinical appropriateness. “In the absence of there being some plague that has caused spines to start dissolving—the spines of aging people are not much different than they were in last 50 to 60 years. The gross increase in reported pathology and reported necessity of involved surgeries, it’s not a smoking gun, but certainly something smells rotten, that’s for sure,” said Dr. Eugene Carragee, a professor of orthopedic surgery at the Stanford University School of Medicine and former chief of the spinal surgery division. And for indications that are commonly thought to benefit from the procedure, a recent New England Journal of Medicine study of spinal surgeries in Norway found that patients who underwent less costly decompressions alone experienced equivalent pain relief as patients who also had spinal fusion surgery. The British Medical Journal’s meta-analysis relies entirely on randomized controlled clinical trials, the gold standard in research. But the absence of other forms of information, such as observational studies and real-world case studies, is a limitation. The article also doesn’t account for surgeons’ experience and medical judgment. Physicians aren’t casually doing surgeries they know to be useless. But they aren’t necessarily considering the clinical evidence when deciding what to recommend, and they aren’t likely to have any encounters with the patients years into the recovery period, except in cases of complications. So they may not really understand what is and isn’t effective. “They get up in the morning and think, ‘What can I do best for my patients? I don’t need (randomized controlled trials). I’ve seen the benefits in my patients, and they get better,” said Jonathan Skinner, a professor at the Dartmouth Institute who studies the relationship between innovations and healthcare cost growth. “But once the surgery is done, the surgeon doesn’t see the patient anymore unless there’s a problem,” Skinner said. “It’s hard for any surgeon to evaluate, and there’s a sort of a bias toward thinking about the successes and ignoring the non-successes.” The benefit of randomized controlled trials is they provide hard evidence about whether a medical intervention works, what complications are possible and how to account for the placebo effect. This kind of research offers the best possible evidence to allow clinicians and patients to make risk-benefit calculations. “If, on average, this thing doesn’t work, the burden is on you to tell me why for this particular patient, it’s going to work, beyond just a faith-based argument,” said Dr. Vikas Saini, president of the Lown Institute, a nonpartisan think tank and research organization that focuses on unnecessary care and other healthcare issues. “Some skepticism is warranted, not enough to shut down those surgeries, but enough to say, let’s be careful.” Spinal fusions do, indeed, carry risks. Spinal fusions for stenosis and other conditions not backed by strong evidence of effectiveness are associated with poor outcomes, according to research the Lown Institute in collaboration with Australian academics published this year. Out of seven low-value procedures, inpatient spinal fusions were affiliated the most with hospital-acquired conditions, adverse patient safety indicators and unplanned hospital admissions after outpatient procedures, their review of Medicare claims from 2016 to 2018 found.

Device industry influence

The rise of spinal fusions is also complicated by an industry built up around these procedures. The implantable medical device market was worth $211.3 billion between 2014 and 2017. About 75% of neurosurgeons and orthopedic surgeons received payments from device manufacturers, and were among the 20 specialties that attracted the most device company dollars, according to a Health Affairs article published in April. Orthopedic surgeons received almost 35% of device payments from the top 10 manufacturers from 2014 to 2017, the largest share among all medical specialties and equaling about $828 million.

Prior to the advent of implants, most surgeons just used bone grafts for fusion, said Dr. Richard Deyo, a professor at the Oregon Health & Science University School of Medicine who studies back pain. But clinical evidence shows that patients experience about the same level of pain relief with bone grafts as they do with implants, he said. “These companies market what they sell very aggressively to surgeons. It’s a huge business,” he said. “Of course, the costs are dramatically higher when you add the hardware.”

Surgeons usually make the decisions about whether to use a medical device, and what kind, for spinal fusions. But the Food and Drug Administration doesn’t subject medical devices to the same level of scrutiny as it does prescription drugs.

Device applications don’t always include randomized controlled trials that prove safety and efficacy. Most devices go through the FDA’s 510(k) process, which requires them to prove that their new products are equivalent to an existing device. After approval, devicemakers can then tout their products as the latest and greatest on the market.

“The question is whether a company with a marketing campaign is able to capture a significant portion of the market based on very-low quality data,” Carragee said. “That’s a regulatory problem, and also an early adopter problem in the United States. There’s a lot of talk about the early adopters as giving their practices a competitive edge. That reflects how people think.”

Research on what devices in a category are better than others is rare, and published studies generally do not name the manufacturers of the products being analyzed. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute—funded by the federal government to do comparative effectiveness research—sought participants for studies on medical devices and other treatments for back pain in 2016, but didn’t receive enough high-quality applications to carry out the plan, a spokesperson said.

That leaves surgeons with scant evidence to guide their decisions, Deyo said. “When you look at one particular study, you have to just sort of pretend that they’re all the same, when in fact the companies would say their product is better than the other products,” he said. “But there are no head-to-head comparisons, which literally might make a real difference to patients in terms of their costs and their outcomes.”

Managing costs

Value-based care organizations that manage orthopedic and other musculoskeletal care have become more common. That includes Healthcare Outcomes Performance Co., which partners with insurers like Blue Cross of Arizona and United Healthcare of Arizona to discourage unnecessary and spinal surgeries. The firm creates care pathways and hands out bonuses based on outcomes, cost of care and adherence to clinical guidelines.

“If nobody’s done the level-one studies, we’ll put together a clinical consensus group and say, ‘Given the information that we have today, what should we be doing?’ And then we’ll make a recommendation based on that and expect folks to follow that recommendation,” said Dr. Wael Barsoum, president and chief transformation officer of Healthcare Outcomes Performance Co. “If we can assume for a moment that if we give clinicians the right tools, that they’ll follow them, then the model works.”

The organization also has another vertical that works with health systems such Ascension Florida and Gulf Coast to manage musculoskeletal-associated practices, including managing contracts with devicemakers. But even with that service, the value comes from bargaining for a cheaper price, and not from science-based evidence. Surgeons still call the shots on what products they want to use.

Most manufacturers are working to create less expensive devices, develop better implant procedures and use technology such as surgical robots and sensors that monitor patients’ progress, Barsoum said. “I would tell you probably 50% of devices today, there’s active innovation in turn of how to plan and execute, as well as how to manufacture, and probably 50% are kind of the same old way they were,” said Barsoum, who is a paid consultant of medical device company Stryker.

The administrator’s role

While doctors largely make the decisions about what procedures patients need and what devices to use, there may be a role for health system leaders to play in managing spinal fusion utilization. Rising medical costs are leading healthcare leaders, and patients, to question potentially wasteful treatments, the Lown Institute’s Saini said.

“The public expects their doctors to make care decisions, but I will also say the public expects doctors to make their medical decisions on the basis of the best interest of the patient,” Saini said. “It is now going to become more relevant for hospital administrators to do their homework on appropriateness and inappropriateness.”

But shaking things up might not be so easy unless the doctors themselves go along with it, Skinner said. Making the wrong move at the wrong time could even lead to more potentially dubious surgeries, he said. “The worst thing you could do as a CEO is to lose money in the hospital. If you go in and you say, ‘You’re not going to do as many surgeries,’ the surgeons leave. They go across town. They start up their own practice,” Skinner said. “Then you have to hire new surgeons and you end up with twice as many surgeons as you started out in a region.”

Related Article  Reducing spinal fusions in the real world

Reducing spinal fusions in the real world

Source link : https://www.modernhealthcare.com/clinical/spinal-fusion-surgeries-too-quick-cut