Traffic light nutrition labels slapped on the front of biscuits and crisps do work and help people eat healthier, scientists insist.

The colour-coded markers found on the front of pre-made foods are a familiar site in supermarkets and corner shops.

Ministers urged manufacturers to adopt front of packaging labels a decade ago, in an attempt to tackle spiralling obesity rates by flagging products high in saturated fat, sugar and salt.

However, critics at the time warned it would not work because it was too simplistic, with foods containing helpful fats, such oily fish, falling afoul of the system while others such as diet fizzy drinks got a free pass.

Now an international analysis into the public health impact of health warnings on the front of packaged has backed up the system.

Food packaging label warnings such a the UK’s were found to be an effective way of encouraging people to eat healthier, new research has found

Colour coded food warning systems ,like the one used in the UK, was found to be good at encouraging people to eat better, whereas written warnings were found to be better as discouraging people from choosing unhealthy food and drink

The results have prompted campaigners to call for the UK system, which is currently voluntary, to be expanded.

Analysts reviewed 134 studies which measured how effective food packaging health warnings were on encouraging people to make healthier choices.

These studies were undertaken between 1990 and 2021 and were from Europe, Latin America, and North America.

Two of these were traffic-style systems — the UK’s and Nutri-score — which is used in some EU nations, such as France and Germany.

The other two were written warning systems used in Chile and California, where, for example, a drink with added sugar will have a label saying it may could contribute to obesity and tooth decay.

All four systems were found to encourage people to eat healthier, researchers found. But there were some differences.

Colour-coded labels, such as the traffic light system, encouraged people to choose healthier meal and drink options.

Whereas written warning systems were better at discouraging people from buying unhealthy items, according to results published in the PLOS Medicine.

Dr Jing Song of Queen Mary University, London, said the results should serve as a wake-up call to food manufacturers, adding the system should also be expanded to menus.

‘Food manufacturers must now get on board in efforts to improve the nation’s health by committing to putting front-of-pack labels across all their food and drink products and on menus,’ she said.

Campaign group Action on Salt and Sugar’s policy manager Mhairi Brown welcomed the research and said the UK Government should act to expand the system.

‘This research provides clear evidence that labelling works,’ she said.

‘We are now urging the Government to make labelling mandatory across all products as this would force manufacturers to show consumers, at a glance, if the product is healthier or less healthy – and hopefully encourage them to reformulate to reduce levels of salt, sugar and saturated fat.’

The Government is due to respond to the the National Food Strategy report drawn up by the Westminster’s food tsar Henry Dimbleby to tackle the nation’s obesity.

It included plans for a ‘snack tax’ on salty and sugary food – although Boris Johnson has dismissed that idea outright.

Another suggestion in the strategy was for a new law requiring food companies with more than 250 employees to provide an annual report on the amount of food they sell which is high in saturated fat, salt and sugar.

There were nearly 8million deaths worldwide from poor diet choices such as high salt intake and low wholegrain intake, according to the authors of the new research.

And the National Food Strategy report identified that poor diets contributed to 64,000 deaths a year in England.

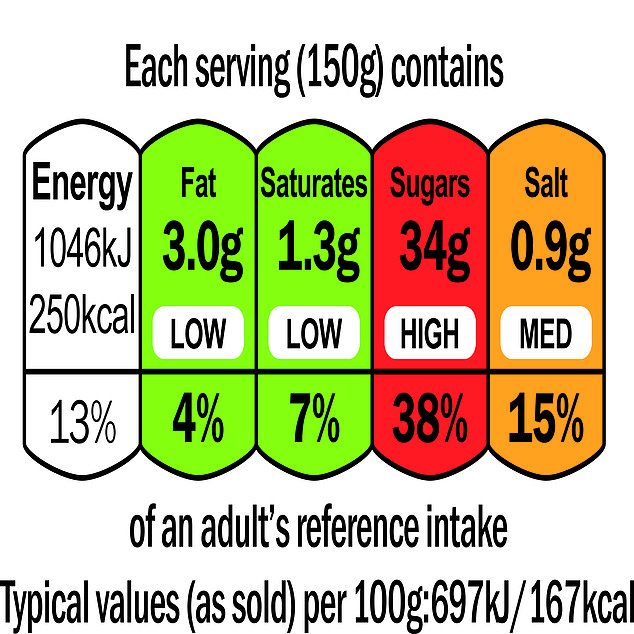

The UK’s colour code system asses food on four categories, qualities fat, saturated fat, sugar and salt.

Foods are given a ‘red’ light for saturated fat if they are more than 5 per cent saturated fat, ‘amber’ between 1.6 and 5 per cent; and ‘green’ for 1.5 per cent or less saturated fat.

For sugar, it’s ‘red’ if it makes up more than 22.5 per cent of the food, ‘amber’ between 5.1 and 22.5 per cent, and ‘green’ if it’s 5 per cent or less. As for salt, it’s ‘red’ if foods are more than 1.5 per cent salt, ‘amber’ between 0.4 and 1.5 per cent, and ‘green’ if 0.3 per cent or less.

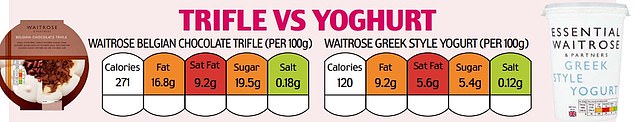

But critics of the system have pointed out that it is too simplistic, with the merits of some healthy food ignored by the traffic light system.

For example a chocolate trifle and tub of Greek yogurt score the same on the traffic lights system.

This is despite the trifle containing more added sugar and having less health benefits, such as more calcium, than the yogurt.

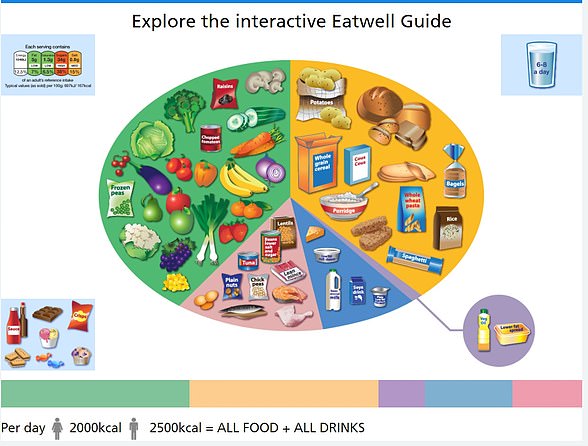

WHAT SHOULD A BALANCED DIET LOOK LIKE?

Meals should be based on potatoes, bread, rice, pasta or other starchy carbohydrates, ideally wholegrain, according to the NHS

• Eat at least 5 portions of a variety of fruit and vegetables every day. All fresh, frozen, dried and canned fruit and vegetables count

• Base meals on potatoes, bread, rice, pasta or other starchy carbohydrates, ideally wholegrain

• 30 grams of fibre a day: This is the same as eating all of the following: 5 portions of fruit and vegetables, 2 whole-wheat cereal biscuits, 2 thick slices of wholemeal bread and large baked potato with the skin on

• Have some dairy or dairy alternatives (such as soya drinks) choosing lower fat and lower sugar options

• Eat some beans, pulses, fish, eggs, meat and other proteins (including 2 portions of fish every week, one of which should be oily)

• Choose unsaturated oils and spreads and consuming in small amounts

• Drink 6-8 cups/glasses of water a day

• Adults should have less than 6g of salt and 20g of saturated fat for women or 30g for men a day

Source: NHS Eatwell Guide

Advertisement

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-10060491/Traffic-light-nutrition-labels-slapped-biscuits-work-study-claims.html