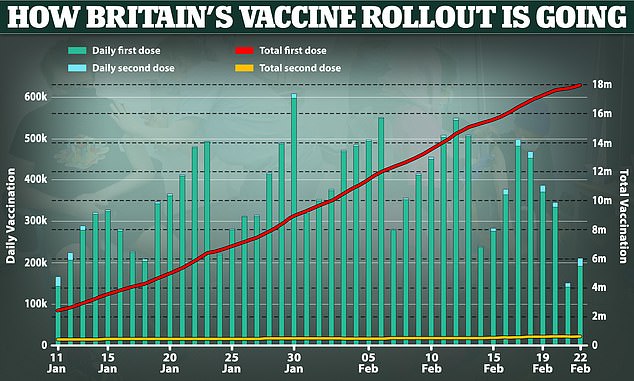

Britain’s vaccine rollout has slowed down over the past two weeks with ministers and manufacturers pointing the finger at each other for the hold-up.

With a successful immunisation drive crucial to Britain’s hopes of easing restrictions over the spring, critics say it is vital the programme picks up speed to avoid Boris Johnson’s ambitious plans getting ‘derailed’.

Just 192,000 people were vaccinated on Monday and 142,000 on Sunday, in two of the lowest daily tolls since the mammoth NHS operation began to gather steam at the start of the year. A further 327,000 were done yesterday; down on last Tuesday.

Ministers have repeatedly blamed the ‘lumpy’ supply of vaccines as being the ‘rate-limiting factor’ of the programme, and the UK’s reliance on just two companies’ jabs makes the situation precarious.

Education Secretary Gavin Williamson today said there was ‘no problem’ with the supply chain and Professor Jonathan Van-Tam, deputy chief medical officer, agreed that ‘fluctuations’ were anticipated.

Officials say shrinking deliveries were expected because Pfizer had to improve its key factory in Belgium at the start of the year, and AstraZeneca’s production was slower to get off the ground than planned.

However, both drug giants have insisted that there are no unforeseen issues with the supply chain, as Nicola Sturgeon said Scotland’s rollout couldn’t speed up until ‘the supplies start to flow in greater volumes again’.

And the concerns spread wider than Britain when an EU official revealed that AstraZeneca is now set to deliver only half of the planned doses to the continent in the second quarter of this year as the firm recovers from a row with the bloc earlier in the year about its supply commitments.

Despite fears that deliveries are slowing down, Matt Hancock has promised ‘bumper’ weeks in March to compensate for the lag. Supply figures published by the Scottish Government in mid-January appeared to back his claims, with the number of doses being delivered next month set to be significantly higher.

Here, MailOnline digs into why Britain’s vaccination drive has slowed down:

The UK has one of the most advanced vaccination programmes in the world, reaching 18million people already, but Sunday and Monday saw its progress slow down

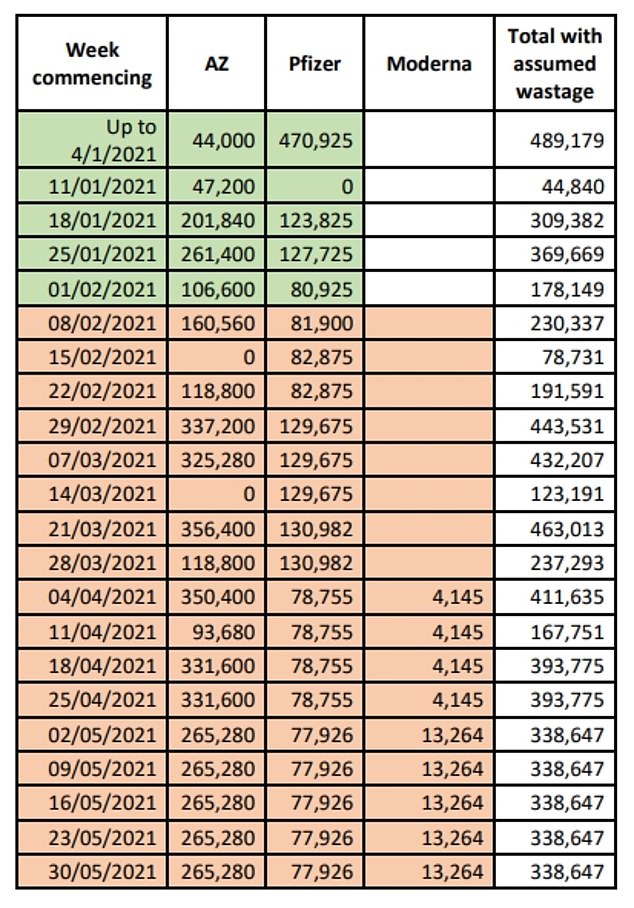

Delivery schedules published by the Scottish Government in January and later removed from its website showed a scheduled dip in stocks in February followed by a surge in availability in March

What slowed down Pfizer’s vaccine?

One of the biggest hold-ups in vaccine delivery appears to have been Pfizer doing maintenance work at its manufacturing facility in Belgium.

Pfizer is the longest-running supplier of vaccines to the UK and has been shipping its jab since it became the first in the world to go into use in December.

As part of preparing to produce hundreds of millions of doses for countries around the world, the company admitted in January that it would be delaying deliveries.

A frustrated EU Commission said the delay was caused by ‘modifications at the plant’ and Pfizer planned to have finished them by mid-February.

Pfizer confirmed the disruption would affect all countries in Europe and told the Financial Times at the time: ‘Although this will temporarily impact shipments in late January to early February, it will provide a significant increase in doses available for patients in late February and March.’

The Scottish Government plans showed that the deliveries from Pfizer would fall by a third from around 128,000 doses in the final week of January to 80-83,000 per week throughout February before spiking back to 130,000 or more in March.

Scotland gets around eight per cent of the UK’s vaccine supply, suggesting the deliveries for the UK as a whole may have changed from 1.6million per week to 1m.

Pfizer told MailOnline yesterday there were ‘no UK supply challenges’ and deliveries were arriving as planned.

Pfizer had to make ‘modifications’ at its manufacturing facility in Belgium which led to delays to deliveries of the vaccine to countries all over Europe

What slowed down AstraZeneca’s vaccine?

The UK’s other major vaccine supplier, AstraZeneca, is making up for the majority of jabs being given out and is expected to be supplying 2million doses per week.

This rapid pace of delivery came later than expected, however, which delayed the NHS’s plans to roll it out to care homes and GP surgeries across the country.

Mid-January had been the original target for two million per week, The Times reported at the start of the year, but this was pushed back by a month.

In a briefing on January 13 AstraZeneca president Tom Keith-Roach said the commitment would be met ‘on or before the middle of February’.

AstraZeneca slashes EU delivery expectation by half

AstraZeneca told the European Union yesterday it would not be able to deliver on the EU’s vaccine orders amid supply issues.

The firm had committed to supplying the bloc with 180million doses in the second quarter of 2020.

But an EU official involved directly in talks with the firm, said the company had warned it could now only ‘deliver less than 90million doses’, according to Reuters.

Britain has ordered 100million doses of the Oxford vaccine and it is one of two Covid jabs being rolled out on the NHS.

Asked about the EU official’s comment, a spokesman for AstraZeneca told Reuters yesterday: ‘We are hopeful that we will be able to bring our deliveries closer in line with the advance purchase agreement.’

Later in the day a spokesman in a new statement said the company’s ‘most recent Q2 forecast for the delivery of its COVID-19 vaccine aims to deliver in line with its contract with the European Commission.’

He added: ‘At this stage AstraZeneca is working to increase productivity in its EU supply chain and to continue to make use of its global capability in order to achieve delivery of 180 million doses to the EU in the second quarter.’

Earlier this week, AstraZeneca said that although there had been ‘fluctuations’ in supply at plants, they were still ‘on track’ with orders with no issues with delivery of the UK-manufactured vaccine.

A spokesman for the European Commission, which coordinates talks with vaccine manufacturers, said it could not comment on the discussions as they were confidential.

He said the EU should have more than enough shots to hit its vaccination targets if the expected and agreed deliveries from other suppliers are met, regardless of the situation with AstraZeneca.

Advertisement

The Scottish delivery figures show that AstraZeneca’s supplies were also scheduled to be low in February.

They would fall from a high of 261,000 doses in a week in late January to none at all in one week in the middle of the month, before escalating to more than 300,000 per week from the beginning of March.

A spokesman for AstraZeneca said on Monday that although there had been ‘fluctuations’ in supply at plants, the firm was still ‘on track’ with orders.

Why are the UK and Europe being affected differently?

Pfizer’s manufacturing issues appear to affect the European Union and Britain equally, but AstraZeneca’s are different because it manufactures the vaccines in different places.

The AstraZeneca vaccine is a natural product – it is a genetically engineered virus made to look like the coronavirus – so must be grown naturally.

The cells needed to make the jab will only reproduce as fast as they naturally can, and astronomical quantities of them are needed, which means the process will always take a minimum amount of time.

AstraZeneca says it takes three months, on average, to make each batch of the vaccine.

Numerous ones are made at the same time but this means that there is an upper limit to how much or how fast one plant can make jabs.

And the yields of these natural batches are also not entirely controllable – the company said it had not produced as much as it had hoped at the start of the production.

Low yields at major European supply plants in Belgium have devastated supply plans on the continent, but Britain makes its own supply in England where the success rate has been higher.

Is there an easy solution?

The UK’s ‘lumpy’ supply cannot be improved easily because there is no quick fix for such a huge manufacturing operation.

Other countries have vaccine orders of equal or higher priority – Pfizer is being used widely in Europe, for example, and Moderna is still unavailable to the UK because it was later to place orders than the US and EU.

And of the vaccines Britain is already receiving, manufacturing cannot be sped up infinitely.

Professor Jonathan Van-Tam, England’s deputy chief medical officer, explained on Sky News today: ‘There are always going to be supply fluctuations.

‘These are new vaccines, by and large the manufacturers have not made them or anything like them before.

‘The process of making a vaccine is one where, basically, you set the equipment up and leave it all to do its thing – a bit like beer-making really.

‘What you get at the end is not something that you can say is identical every time in terms of the yield, the amount of doses you can then make from that batch.’

He added that it will take ‘a few months’ before the manufacturers can get into a steady routine, he said, and there were also ‘global supply constraints’.

Professor Jonathan Van-Tam (left), England’s deputy chief medical officer, said ‘There are always going to be supply fluctuations’, and NHS chief Sir Simon Stevens (right) said the pace of vaccination could double in the second phase of the rollout

Will the UK’s vaccine rollout speed up?

Ministers insist that the vaccination programme will speed up significantly in March when supplies become bigger and more regular.

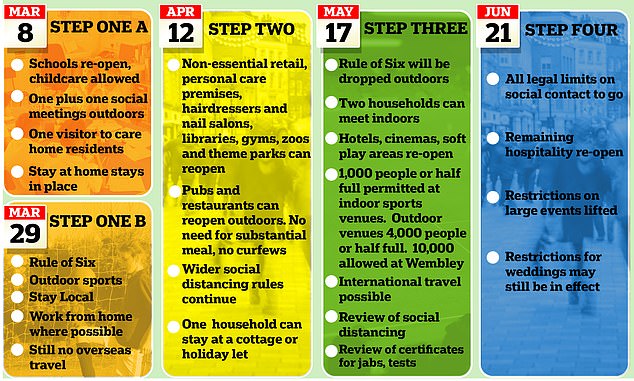

The Government is aiming to vaccinate everyone over the age of 50 by May, and Boris Johnson said he plans to offer a first dose to all adults in the UK by July 31.

Moderna’s vaccine, of which the UK is expecting seven million doses and has already approved for us, will start to be delivered from the end of March.

Sir Simon Stevens, chief executive of NHS England, suggested the rollout could even go twice as fast in its second phase in order to keep reaching people at the same rate as now while also giving out the second doses to elderly people.

‘Compelling’ real-world data from Scotland shows one dose of either jab cuts risk of being hospitalised by up to 95%

Covid vaccines being used in Britain are working ‘spectacularly well’ and cutting hospital admissions caused by the virus by as much as 95 per cent, according to the first real-world evidence of the roll-out.

Researchers yesterday called the results ‘very encouraging’ and claimed they provided ‘compelling evidence’ that they can prevent severe illness.

Scientists counted Covid hospital admissions in Scotland among people who had had their first dose of a jab and compared them to those who had not yet received a dose of either the Pfizer or Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine.

In a ray of hope for Britain’s lockdown-easing plans, results showed the jabs slashed the risk of being admitted to hospital with Covid by up to 85 and 94 per cent, respectively, four weeks after a single dose.

The study — carried out by academics from the universities of Edinburgh and Strathclyde, as well as Public Health Scotland — was the first of its kind. But it currently doesn’t have enough data to analyse how well the jabs prevent death or stop transmission of the virus.

Lead researcher Professor Aziz Sheikh said: ‘These results are very encouraging and have given us great reasons to be optimistic for the future. We now have national evidence that vaccination provides protection against Covid hospitalisations.

‘Roll-out of the first vaccine dose now needs to be accelerated globally to help overcome this terrible disease.’

Advertisement

He said at a Downing Street briefing last week: ‘In this next phase, the second sprint, actually we’re going to be vaccinating a larger number of people than in the first sprint.

‘And overall, although supply will vary week to week and we’ve got to adjust accordingly, we may be giving up to twice as many vaccinations overall – given we’ve got to be doing second doses as well – than we have done in the first sprint.’

Health Secretary Matt Hancock also yesterday said vaccination figures would stay low for the rest of this week in an interview with LBC’s Nick Ferrari.

He said it will be a ‘quieter week’ for the vaccine rollout because of a drop in stockpiles, warning that the success of the drive was ‘all about supply’.

Mr Hancock added: ‘We have got a quieter week this week and then we’re going to have some really bumper weeks in March.’

Pointing the blame at vaccine manufacturers, he also claimed there has been ‘ups and downs’ in the delivery schedule.

Why is it important for the rollout to progress quickly?

Britain’s vaccination programme must go quickly because the country’s entire route out of lockdown hinges on it.

Boris Johnson’s plans to lift lockdown rules are based on vaccinating the majority of people who are likely to die if they catch coronavirus.

The more people who can be successfully vaccinated with at least one dose, the faster the rules can be loosened because the lower the death count of the third wave could be expected to be.

A third wave of the virus is now inevitable, with cases expected to skyrocket when lockdown ends, but the impact of this will be more tolerable if the majority of adults in the country are immune to the virus.

Professor Paul Hunter, from the University of East Anglia, said yesterday that Britain will struggle to stick to its plans if vaccination rates don’t pick up ‘very soon’.

Professor Hunter pointed out that the rapid decline in positive coronavirus tests seen earlier in the lockdown appears to be levelling off now, and the number of people being vaccinated each day are dropping lower at the same time.

He warned: ‘Taken together, these two observations are concerning…

‘If more of our vulnerable people were protected from severe disease through immunisation, then we could allow some increase in numbers without posing a substantial extra risk of severe disease and hospitalisation.

‘However, a lot of people admitted to hospital with Covid are still not in the groups where vaccination has been completed.

‘If vaccination rates do not pick up very soon, then we will struggle to give enough people their first dose before we have to allocate more and more of our available doses to people’s second injections.

‘This could lead to more potentially vulnerable individuals being unprotected for a lot longer than we had expected as we try to relax restrictions further. This would have the real potential to derail the UK’s road plan for coming out of lockdown.’

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-9294749/What-Britains-Covid-vaccine-slowdown.html