I carried my baby in a tikinagan—an Indigenous parenting practice once restricted and now reclaimed.

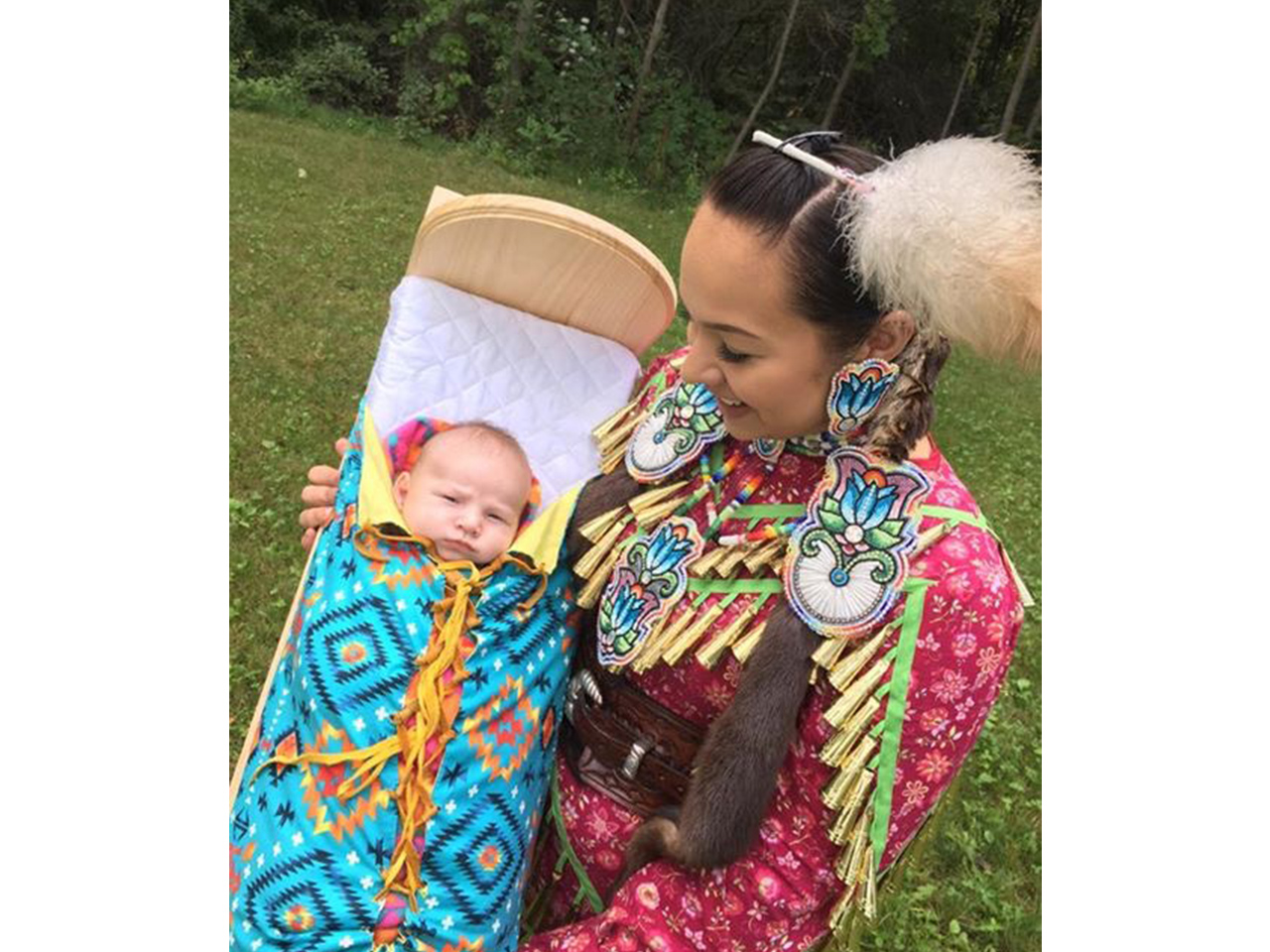

Andrea with her daughter RJ. Photo: Courtesy of Andrea Landry

Cradling her in my arms, I looked down at her delicate features. Her eyes were open, yet sleep was setting in. I carefully placed her in her purple and floral mossbag, explaining to her what I was doing. She would make sounds, the tiny noises that only new babies make. I kissed her forehead and slowly began to tie the mossbag, from the bottom up.

As I tied, I whispered prayers, surrounding her, protecting her. I imagined the generations of Indigenous mothers before me who similarly laced babies up in mossbags with love and prayers, knowing that colonialism could never take our traditional child-rearing and kinship practices away. I picked my daughter up, supporting her back and head, and placed her in the tikinagan. By now, she was asleep.

Staring at the floral beadwork, created by relatives two generations ago, and the hide holding the fabric together to the board, I felt a deep gratitude, knowing that I am raising my daughter with this traditional knowledge. I began to tie and weave again. As I tied, I prayed some more. I smiled knowing that generations of mothers before us, within our bloodline, have also done the same thing. I carefully leaned the cradleboard against the wall, preparing to go outside, then placed her on my back. By now, she was in a deep sleep, surrounded by my love and prayers, and by generations of Indigenous-based child-rearing practices. This is where she napped the best.

Natalie Restoule with son Nova Restoule. Photo: Courtesy of Andrea Landry

The tikinagan plays a fundamental role in child-rearing practices of Indigenous families because it is so interconnected to life in the womb for the infant. We have all experienced it. Going from that place of warmth, comfort and security in the womb of our mother, and later being born and forced to abandon that warmth, comfort and security. This is where the mossbag and tikinagan come into play. Tikinagans were historically created for security, safety and protection. Wrapping babies in mossbags and placing them in the tikinagan instantly creates a womb-like atmosphere, minimizing feelings of insecurity and fear of the unknown.

In order for this traditional Indigenous motherhood system to work, all parts of the mossbag and tikinagan must be fastened correctly and completely; however, prayer and love must be the source of it all. While safely fastened inside, my daughter RJ would either nap or simply look around, experiencing the world from the safe confines of her tikinagan. I was able to weed the garden, take walks in the bush, set and check rabbit snares, and do other land-based practices. I had complete confidence that she was safe. And each time I looked at her, as she leaned against a tree or the house, she was content.

In Anishinaabemowin, we call it a tikinagan. The direct translation: “tik” means tree or wood, and “nagaan” means a vessel. However, much like our original Indigenous names, colonialism renamed it. In English, it’s called a cradleboard. For me, using the term tikinagan, in my language of Anishinaabemowin, rather than “cradleboard” plays a significant role in the reclamation process of this Indigenous kinship practice. Using my mother tongue for practices that were originally mine, as an Indigenous mother, is an integral element in the maintenance and longevity of Indigenous systems.

The tikinagan, wrapped with its leather and wood, comes with many teachings of motherhood and womanhood that span generations before us. These practices and these teachings were, and are still, restricted through colonial acts of oppression and attempts to assimilate Indigenous parents and families. However, using tikinagans is essential to the foundation of kinship development after a baby’s birth for my own ancestors and many other Indigenous families. In doing so, we are resisting systems that have attempted to silence us for far too long.

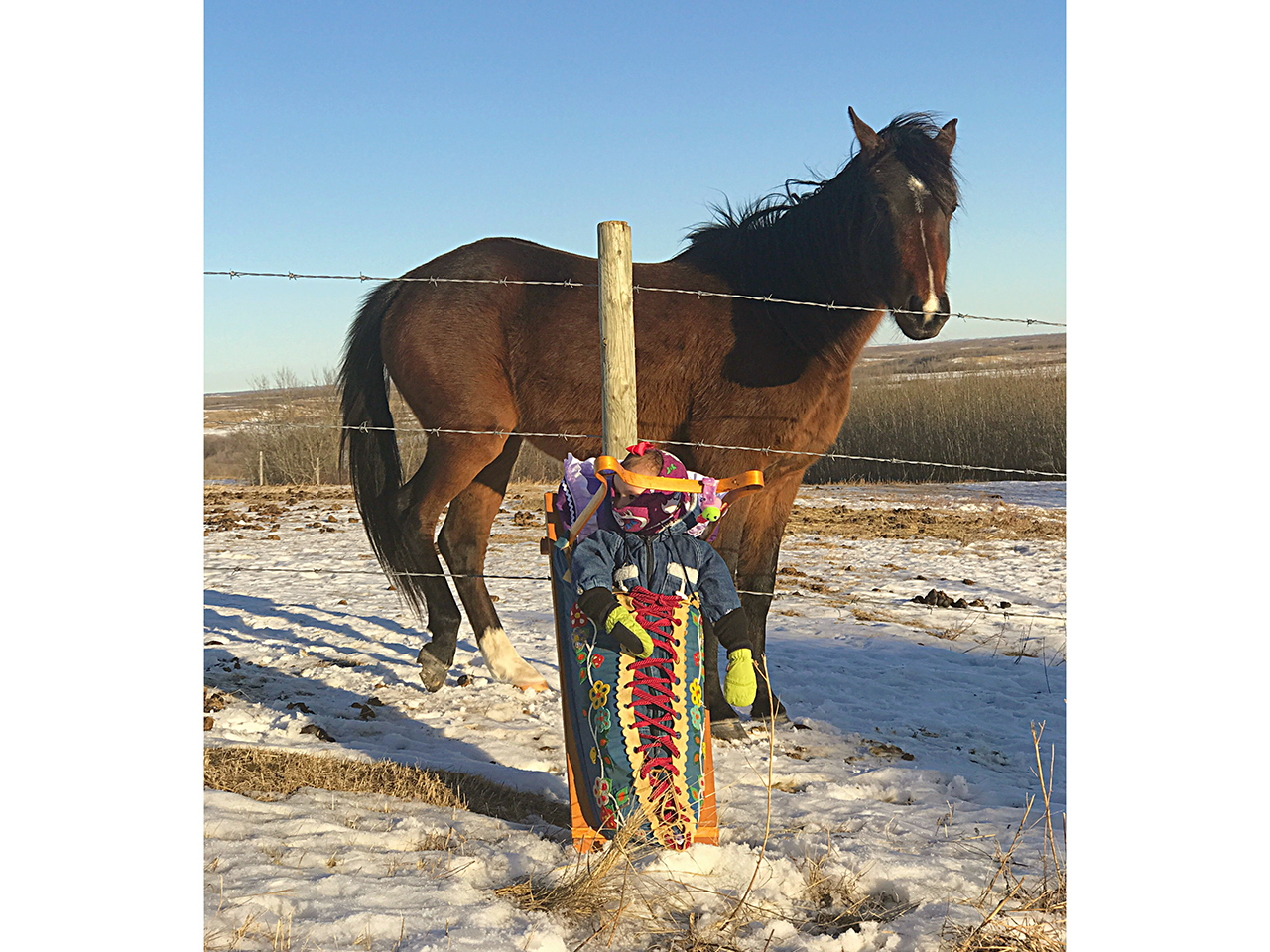

Margaret Wallace and Vincent Wallace. Photo: Courtesy of Andrea Landry

Why I used a tikinagan

Because of residential schools, and because Indigenous kinship practices were forcefully extracted from families when Indigenous children were stolen from their homes, my mother didn’t have the tools and resources to carry on these practices when she became a mother. The tikinagan, and the kinship teachings that came with it in my family, were buried in the soil of my homelands. Yet as generations healed and spoke, it made its way back into my family’s life.

Although I was never raised in a mossbag and tikinagan, the innate knowing to pray, and how tightly to secure RJ within it, was automatically present. With help from my mother-in-law, and with the knowing from generations of Indigenous kinship in my blood, I was able to continue a practice that had existed since before anyone can remember.

These teachings are only meant to be passed down orally, as kokums (grandmothers) tell mothers and mothers tell daughters. Many of these teachings are only heard during the very sacred time when one is preparing for motherhood. What I can share with you are some of the basic elements that make tikinagans so special. The work of Alex Nahwegahbow, an Indigenous scholar, and the teachings within my own kinship system provided the knowledge here. This knowledge is important— knowledge that every Indigenous mother deserves to know, and knowledge that brought me one step closer to knowing who my mother and kokum were, underneath their colonially caused trauma. It was the knowledge that ultimately opened up this place of love and forgiveness to the generations of mothers before me in my family, who struggled from their own pain. It was knowledge that healed.

Babies in their tikinagans, watching the community and families as they worked close by, witness the hard work of their nohtawis (fathers) and nikawiys (mothers) on the land. When I would work outside on the land with RJ in her mossbag and tikinagan, she would face me and the trees, watching the leaves in the breeze. She would often fall asleep, but when she was awake, her eyes would scan her surroundings. Being secured in the tikinagan was showing her how to be observant, how to learn from watching, how to learn to listen. It was her way of learning from the land and, ultimately, falling in love with the land. It was teaching her that the land will always love her.

Endawnis Spears with son Sowaniu Spears. Photo: Courtesy of Andrea Landry

Making a tikinagan

There are times during motherhood, Indigenous and otherwise, when our infants decide they do not want to sleep, or they are simply uncomfortable and the only way they can sleep is when they are on our chests. Which of course, keeps us awake. But this was where the mossbag and tikinagan came into play. As soon as she was wrapped, RJ would sleep for longer stretches. I would lay her down safely, refuelled by my prayers, and finally get some rest.

Members of a community and families each play a vital role in preparing the different pieces necessary to complete a tikinagan for a mother and her newborn.

The board and bow is to be made by the nohtawi (father) or the moshum (grandfather). The nihkawi (mother) is to make the covering. This provides a balance of kinship—everyone plays a part in ultimately providing security and comfort, and a space for observance and learning for the baby. This process alone shows the significant role that kinship plays within the lives of Indigenous peoples, because prior to the child coming physically into the world, teachings of kinship are being woven into the first place they will sleep.

Today, many tikinagans and mossbags are passed down between generations. Our daughter was carried in a tikinagan that was given to us by one of my uncles. He was wrapped in it when he first came into the world—created by and prayed upon by his uncle and aunty some 50 years ago. I took comfort in the fact that when RJ was uncomfortable and frustrated from living outside of the womb, we would wrap her tight, put her in her mossbag and fasten her inside her tikinagan, like she was still in my womb. Her crying would instantly stop. I wasn’t surprised at the tikinagan’s ability to comfort RJ, as I knew that mothers before me wouldn’t have used it if it didn’t provide comfort.

Despite decades of wear and tear on RJ’s tikinagan, the resilient beadwork is still intact. It is similar to the experiences enmeshed within Indigenous motherhood, and motherhood itself. Although colonialism has attempted to wear us down as Indigenous mothers, and as mothers in general, we remain resilient and strong. And through the sleepless nights, the isolating and lonely days, the teething, fevers and sicknesses, we as mothers, along with our babies, remain connected in a space of deep love.

The benefits of using a tikinagan

The design of the tikinagan is genius for living on the land—hunting, fishing and even everyday land practices. The tikinagan makes all of this easier, keeping baby secure and protected. The tikinagan’s curved bow is designed to prevent injury in case the cradleboard falls forward. The first few times I used the tikinagan with RJ and leaned her against a tree or fence post, there was always the fear that she would fall. This of course never happened—her tiny body was safely nestled inside. I knew in my heart that my ancestors would not have kept using tikinagans for their babies if it was dangerous. Now, pulling her in a sled in the deep snow when she was one-year-old? That was a whole other story. Her first face plant in the snow ended with some cries and required cuddles from mama. The tikinagan provided fewer frozen experiences than that.

Andrea’s daughter RJ. Photo: Courtesy of Andrea Landry

The stability of the tikinagan is shown in more than just the bow. When placed correctly over the bow, fabric (historically animal skins) protects babies from the cold and branches when walking through the bush, and also from mosquitoes and other bugs. With RJ on my back, I could effortlessly walk through bush trails on my way to set up snares for rabbits, knowing she was in a safe space, even when trails were covered in deep snow.

The designs, woven, beaded, embroidered or sewn onto a tikinagan, are specifically chosen to provide protection during this very sacred and sensitive time, as the baby grows and learns about the world. Floral designs are the most popular where I come from in Northwestern Ontario. They use specific plants and flowers that grow in the area, like wild blueberry and strawberry plants. On RJ’s tikinagan, beaded into the fabric, are images of five-petal flowers sprawling amongst the blue.

To be able to provide the same nurturing ways and comfort to my own baby that my ancestors did with their own babies—restrained no more—has been revolutionary.

RJ has grown and learned in her tikinagan—and it connected her to my own family, even though my own mother and kokum had passed on. My mother passed when I was five months pregnant, and deep in my grief, I spent a lot of time on the land with my baby wrapped in her mossbag and tikinagan. Knowing I had a safe space to place RJ, and to be able to engage with traditional Indigenous kinship and child-rearing practices, provided me all the security I needed to heal. And for that, I am eternally grateful.

Andrea Landry is a mother. She teaches for the First Nations University in Regina, and formerly taught for the University of Saskatchewan. She works with communities in the area of grief and recovery, Indigenous motherhood, family healing and Indigenous resurgence. She has a Master’s in communications and social justice and a background in social work.

This article was originally published online in November 2018.

FILED UNDER: Baby care Indigenous Newborn care

Source link : https://www.todaysparent.com/family/parenting/why-i-carried-my-baby-in-a-tikinagan