Bloomberg

Bloomberg

Increasing pressure from COVID-19 patients and their families seeking unapproved treatments puts hospitals in a legal quandary.

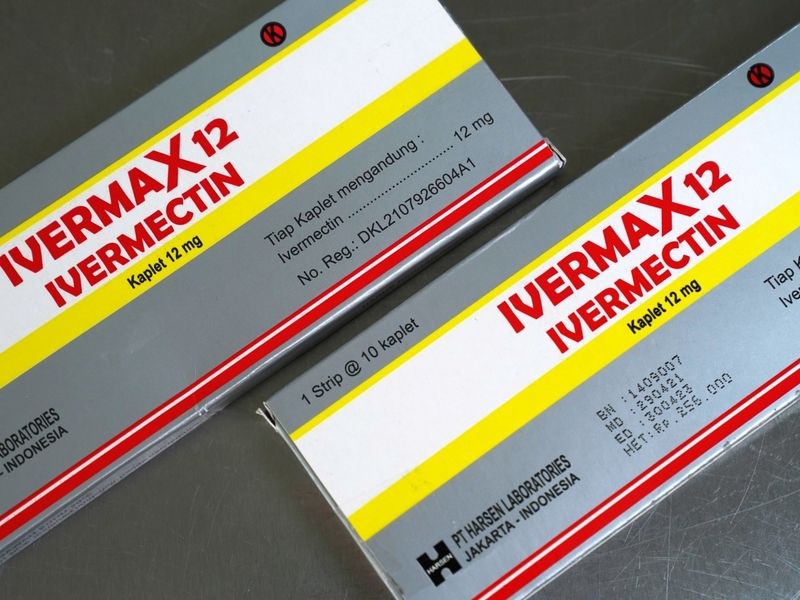

Ivermectin has long been used to kill parasites in animals and humans. But despite being touted as a coronavirus cure by conservative media personalities, the antiparasitic hasn’t proven to be safe or effective for COVID patients. Even so, some are demanding that hospitals administer the controversial drug—and they’re taking their demands to court.

Hospitals could be forced to choose between defying a court order and administering an inappropriate medication, potentially exposing themselves to liability if patients have adverse reactions. Some organizations will be compelled to find workarounds, like west suburban Elmhurst Hospital, which granted an unaffiliated physician emergency privileges to administer ivermectin on its premises. But no decision is without risk.

“There are a lot of things I will ask a physician to do, but something I have never—and would never—ask them to do is administer a medication or provide certain treatment, particularly if it’s not what they want to do,” says Mary Lou Mastro, CEO of Edward-Elmhurst Health. “I’m not qualified to order them to do that. A judge is not qualified to do that.”

Still, Elmhurst Hospital complied when a DuPage County judge in late April ordered it to give ivermectin to a comatose patient at the request of the patient’s guardian.

Hospital clinicians refused to administer the drug, citing unknowns about how it might interact with the patient’s other treatments, and the patient’s family wouldn’t permit her to be transferred to another facility, says Christine Koman, system claims counsel at Edward-Elmhurst Health. So Elmhurst allowed an unaffiliated doctor to do it.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, public health departments have encouraged hospitals to offer temporary privileges to doctors as a way to alleviate staffing shortages during outbreaks. But industry observers say it’s not a common practice for administering treatments that hospital clinicians aren’t willing to provide.

Illinois is among states that allow some patients with terminal illnesses to get investigational treatments that could help prolong their lives. But whether such laws “can be used to compel a hospital to treat someone they don’t want to is a different issue,” says David Hyman, a professor at Georgetown Law. “It’s also, frankly, a function of how the judge feels about whether they want to get involved in this particular dispute and how sympathetic they are to the plaintiffs versus the defendants.”

Judges have differing opinions, recent ivermectin cases show. An Illinois appellate court judge in July dismissed Elmhurst’s appeal, but two other judges declined to require hospitals to give ivermectin to COVID patients.

A Sangamon County judge last month sided with Memorial Medical Center in Springfield, blocking a hospitalized COVID patient from getting ivermectin. And an Ohio judge this month refused to order West Chester Hospital to treat a patient with ivermectin.

“Judges are not doctors or nurses. We have gavels, not needles, vaccines, or other medications,” Butler County Judge Michael Oster wrote in the Ohio case.

Such cases are unusual and, in most instances, patients will seek out doctors willing to provide unapproved treatments before taking hospitals to court.

“Nobody knows how this is going to play out,” Hyman says. “My bet is judges are not going to routinely start second guessing medical decisions.”

Hospitals that comply with court orders to facilitate inappropriate treatments could face other legal jeopardy. Patients alleging harm from ivermectin could sue hospitals for negligence. Hospitals that administer inappropriate medication also could risk losing their standing with private accrediting organizations, some industry observers warn.

Elmhurst Hospital tried to minimize its legal risk by asking the patient’s estate to sign a waiver of liability. The form was never returned, Koman says.

“The nurses in COVID units are working incredibly hard,” says Mastro. “It’s very complex. It’s intense. And now you have this disruption going on—and the family is creating a lot of disruption, which was adding to the stress and the anxiety of the team trying to take care of this patient,” Mastro says, noting that such disruption factored into the hospital’s decision to grant privileges to an unaffiliated physician.

Some experts urge hospitals to take a harder line.

“You don’t let the public determine what interventions to use,” says Arthur Caplan, a professor and director of the Division of Medical Ethics at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine. “When doctors around the country ask me what they should do if there’s a court order, I say defy it. It would be as if somebody said, ‘I’m going to order you to give bleach to a patient because the president liked that at one point.’ ”

One local hospital is standing firm against a pressure campaign reportedly backed by QAnon, the network known for perpetuating conspiracy theories.

AMITA Health Resurrection Medical Center Chicago in Norwood Park refuses to give the drug to a hospitalized COVID patient, despite calls and emails running “well into the hundreds” urging it to do so, spokeswoman Olga Solares says.

“Following FDA and CDC guidance, we do not prescribe or administer ivermectin for the treatment of COVID-19 at AMITA Health,” Solares says.

Other large Chicago-area hospitals say some patients have asked about ivermectin, but they’re not administering the drug for the treatment of COVID-19, in accordance with the current FDA guidance.

“In the future, we may participate in a large clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of ivermectin for mild outpatient COVID-19,” University of Illinois Hospital’s Chief Quality Officer Dr. Susan Bleasdale says in an email.

Pharmacies are also caught in the ivermectin crossfire, with prescriptions for the antiparasitic drug up 24-fold, according to an August CDC analysis.

While drugstore chain CVS doesn’t have a policy that restricts its pharmacies from filling prescriptions for ivermectin, “pharmacists are empowered to use their professional judgment when reviewing a prescription and a prescriber’s diagnosis,” spokeswoman Tara Burke says in an email.

Outside of hospitals, some people are turning to high-dose animal formulations of the drug, like injectables and pastes meant for horses and cows. The American Association of Poison Control Centers reports an uptick in adverse effects associated with the drug as a result.

“I am a little surprised, I guess, that there are people who want to take a veterinary medicine that is not FDA approved but then don’t want to take the vaccine that has had really widespread human trials and is approved,” Chicago Department of Public Health Commissioner Dr. Allison Arwady said recently. “If we ever get good news on ivermectin, we’ll be the first to be talking about it. But in the meantime, your doctor is not going to recommend it and certainly you should never ever take a veterinary formula of a medication.”

Without indisputable evidence that ivermectin is safe and effective for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19, hospitals are likely to continue denying patients access to the drug. Some of those patients, or their families, can be expected to take the matter to court.

“It’s really troubling to see courts forcing hospitals to administer unproven treatments,” says Wendy Netter Epstein, a professor and associate dean of research at the DePaul University College of Law. “A patient’s right to choose their care was never meant to extend that far.”

Related Article  Efforts grow to stamp out use of parasite drug for COVID-19

Efforts grow to stamp out use of parasite drug for COVID-19  Judge orders Ohio hospital to treat COVID-19 patient with ivermectin

Judge orders Ohio hospital to treat COVID-19 patient with ivermectin

Source link : https://www.modernhealthcare.com/providers/covid-patient-ivermectin-demands-put-hospitals-legal-bind