Unesco’s World Heritage Sites programme is not working. It has failed in the way that all idealistic bodies fail when they lose their founding spirit and succumb to the ways of the world.

Unesco was the product of post-war optimism, the longing to reshape the world on a better model, and at the beginning it was led by intellectuals and artists. But then its bureaucracy grew, corruption and nepotism crept in, and it was while trying to clean it up in the 1990s that delegates to the World Heritage Committee ceased to be cultural figures and were replaced by diplomatic emissaries of the member states.

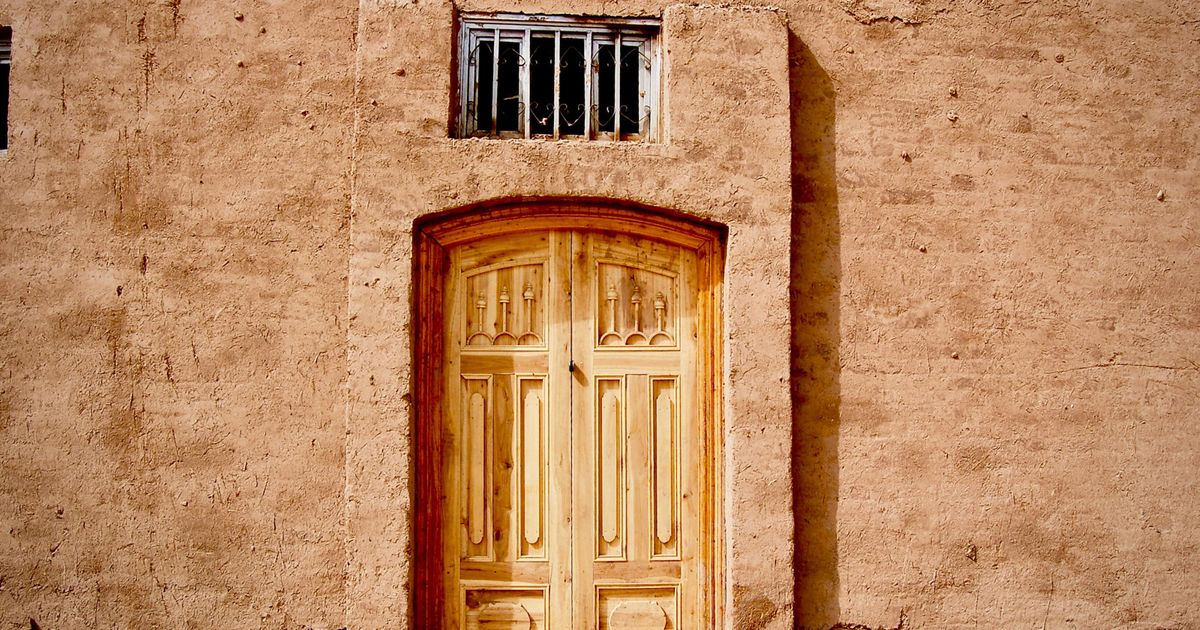

This speeded Unesco, like the UN, down the path of becoming a stage for nationalist politics, the exchange of political favours between countries, and the suppression of embarrassing truths. And now there is institutional corruption. Unesco’s current failure to condemn the cultural genocide perpetrated on the Uyghurs, with the destruction of their ancient city of Kashgar and its mosques, cannot be unrelated to the generous funding the organisation gets from the Chinese government. And the case of Venice is a long-standing scandal. It was threatened by the World Heritage Committee in 2014 with being declared an endangered site but has repeatedly avoided being listed through the connivance of Unesco officials under pressure from the Italian government, another generous contributor to the organisation.

Now, at last, people are rebelling. In November, Francesco Bandarin, a former director of the Unesco World Heritage Centre, and 26 other professionals from the heritage sector launched a new organisation, Our World Heritage, which aims to put Unesco’s feet to the fire. It includes heavy hitters, many of them with a background in Unesco itself or Icomos (the International Council on Monuments and Sites, which gives professional advice to Unesco). A few names: Jean-Louis Luxen, the former secretary general of Icomos and general administrator of the department of cultural affairs of Belgium; Jad Tabet, who insisted, against strong opposition, that Venice at least get debated at the 2016 World Heritage Committee meeting, and is president of the Lebanese Order of Engineers and Architects and of the Arab Union of Architects, and the archaeologist Lynn Meskell of Pennsylvania and Cornell Universities, an expert in the politics of governing heritage.

Their plan is to harness the power of sound information, rapidly drawing attention to situations where heritage is at risk through an online crisis centre, where the public, professionals, NGOs, academics and the media will be able to flag and track sites. They will keep a close eye on the 1,121 Unesco World Heritage Sites, also by employing civil society, to make sure that they are being looked after properly. For example, had Our World Heritage existed, Unesco’s failure to act on the recommendations of the blazingly critical 2015 Icomos report on Venice, commissioned by Unesco itself and then semi-buried, would not have gone unnoticed. Our World Heritage aims to be a global partnership, exchanging news and lobbying efforts, so that in future no one, least of all Unesco, will be able to say, “Oh, we didn’t know.”

In 2021, Our World Heritage is holding a series of workshops on how to build this most effectively, seeking partnerships with other major NGOs, leading up to a big conference in 2022 to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the World Heritage Convention.

It remains to be seen how Unesco’s director general, Audrey Azoulay, takes this, but if she has good political instincts she will welcome it. It could be the saving of Unesco, the shield behind which to redeem itself from the political indebtedness that currently makes a mockery of its high ideals, to the detriment of our very fragile world.

• Anna Somers Cocks is the founder-editor of The Art Newspaper

Source link : https://www.theartnewspaper.com/comment/finally-rebel-experts-come-to-the-rescue-of-unesco-s-failing-world-heritage-sites-programme