Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Elephant and Obelisk may have been his most important collaboration with Alexander VII. Photo Beate Schleep/picture-alliance/dpa/AP Images

Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Elephant and Obelisk may have been his most important collaboration with Alexander VII. Photo Beate Schleep/picture-alliance/dpa/AP Images

When Gian Lorenzo Bernini began his rapid ascent as his generation’s leading sculptor during the mid-17th century, Rome was again in a steady decline. Once among the most prosperous cities in Europe, it was no longer an important business hub—London and Paris had begun to steal its thunder in that regard. It was also no longer the art destination that lured talents like Raphael and Michelangelo during the Renaissance. Add to all this the Thirty Years’ War, which began in 1618 and resulted in millions of deaths, and a quick succession of popes, which only added to the chaos.

Rome was, in other words, a has-been. Then Bernini and Pope Alexander VII started working together and changed all that. “For twelve years, the divinely inspired artist and the imperious pope shared centre stage in the ‘world’s theater’ and during that time they took the ragged remnants of the ancient city and clothed it in Baroque for its many roles, as capital of the Catholic Church, fount of Western civilization and premier tourist destination,” Loyd Grossman writes in his new book The Artist and the Eternal City: Bernini, Pope Alexander VII, and the Making of Rome (Pegasus).

In this fast-paced tome, Grossman makes the case that Bernini and Alexander’s working relationship represented the perfect merger of art and power. Their partnership lasted more than a decade, and was the rare ideal match between a cunning diplomat and a talented artist. Without them, Grossman convincingly suggests, Rome may not look the way it does today.

When it came to working with the papacy, Bernini’s collaborations with Alexander VII were hardly his first rodeo. Depending on who was in power, Bernini was either in high demand or in the doghouse. Urban VIII, for example, took a liking to him—he had Bernini produce what would count as one of his most famous works, the baldacchino at St. Peter’s Basilica, a dramatic bronze canopy with twisting columns, a giant gold crucifix, and ornate gilding. Innocent X, who succeeded Urban VIII and was in power from 1644 to 1655, railed against everything his predecessor stood for. He kept Bernini from working with the pontificate, and the effect was “almost career-ending,” Grossman writes. But the artist was too famous for the prohibition to end his career. He continued receiving private commissions, including his famed Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, completed in 1652.

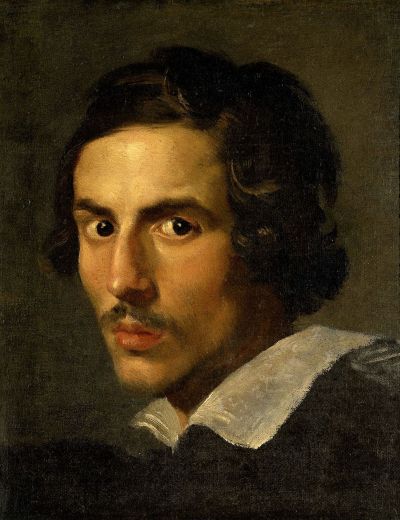

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Self-Portrait, ca. 1623. Via Wikimedia Commons

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Self-Portrait, ca. 1623. Via Wikimedia Commons

There was something different about his relationship with Alexander VII, with whom Bernini grew unusually close. In Alexander’s diaries, Bernini appears more often than any other artist—and there were many other artists with whom Alexander interacted frequently. Bernini and Alexander often met several times a week, and Grossman writes that Alexander “regarded himself not as a mere patron but as a collaborator.”

When Alexander was elected pope in 1655, Bernini was still in high demand. Grossman reports that, during the 17th century, the average Roman worker earned 50 scudi annually. Bernini, by contrast, had a fortune of anywhere between 300,000 and 600,000 scudi by the end of his career. He’d become known for pioneering an extravagant style that could be considered “rather embarrassing, like a guest who talks too loud or someone who keeps bursting into tears,” Grossman writes. Bernini’s style is one of swirling fabrics, overstated emotions, profane sexuality, and largesse. These days, it would probably be considered camp.

It’s hard not to get swept up in Bernini’s work, and those with money during the 17th century fell for it hard. (Never mind that Bernini was poorly behaved, and once even beat his brother with an iron bar for sleeping with his bedmate, who was herself married to someone else in his studio.) The French king Louis XIV liked Bernini so much that he even made a bid to get the artist to leave Rome. But he stayed, and became Alexander’s go-to artist.

Alexander gave Bernini the opportunity to do more than just sculptures. The artist was also enlisted to design a new colonnade for St. Peter’s Cathedral, a new setting for the Cathedra Petri (St. Peter’s throne), and a new layout of what is now the Via del Corso, a major roadway in the capital city’s historic center that Bernini widened in order to keep it from getting jammed with private carriages. An artist as an urban designer? It wasn’t a crazy thought in 17th-century Rome, where the boundaries between artistic mediums were blurrier than they are now. As Bernini’s friend and biographer Filippo Baldinucci wrote at the time, it was “common knowledge, that he was the first to unite architecture, sculpture and painting in a way that they together make a beautiful whole.”

Giovanni Battista Gaulli, Portrait of Pope Alexander VII (Fabio Chigi), ca. 1667. Walters Art Museum

Giovanni Battista Gaulli, Portrait of Pope Alexander VII (Fabio Chigi), ca. 1667. Walters Art Museum

Grossman is a passionate Bernini fan, and his fervor for the artist keeps this book from getting staid. As only a true devotee can, Grossman calls a relatively little-known monument Bernini’s ultimate work for Alexander. It’s a monument that today doesn’t command much attention—or, at least, not as much as Bernini’s best-known works. (Technically, the sculptor Ercole Ferrata crafted it, though Grossman is quick to note that Bernini regularly employed numerous assistants and never credited any of them. The idea was Bernini’s, anyway.) Set in the Piazza della Minerva, near the Pantheon, the work is a statue of a snarling elephant that has on its back an ancient Egyptian obelisk that had been discovered on the grounds of a church in Rome in 1665. Alexander died in 1667, just days before the monument was unveiled.

The work was meant to “exalt [Alexander’s] erudition and still satisfy the demands of modesty,” Grossman writes—modesty, of course, being a relative term when discussing an 18-foot-tall artifact from a fallen empire that was hauled through the streets of Rome. Looking at Bernini’s sketches for it, one yearns for something more extravagant, however. Bernini had toyed with the idea of having the monument perilously perched on a diagonal, or perhaps held atop the backs of sculpted allegorical figures; Alexander’s disapproval and physics prevented both from getting executed. The result, however, is stately and quite impressive, no less. There’s evidence that contemporary audiences loved it—the monument is even depicted in paintings that could be bought as souvenirs at the time, a sign of the work’s fame.

Bernini’s statue for the Piazza della Minerva is hardly the defining work of the Baroque movement. It’s not even Bernini’s best work. But Grossman finds it telling of a certain line of thinking that pervaded the 17th century during the Age of Absolutism, the era when monarchs and religious officials ruled with total control: throw enough money at a project, enlist a particularly good artist, and you may just have on your hands an effective way of communicating authority. Speaking of that tendency, Grossman writes, “If you feel that art exists in a political, social, or religious vacuum, perhaps you should look away now.”

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-news/artists/gian-lorenzo-bernini-alexander-vii-the-artist-and-the-eternal-city-review-1234600264