Lauren Berlant in a still from Shannon Walsh’s film Illusions of Control, 2019. Courtesy Shannon Walsh

Lauren Berlant in a still from Shannon Walsh’s film Illusions of Control, 2019. Courtesy Shannon Walsh

Lauren Berlant fundamentally altered our sense of how language matters, how language can make and sustain alternate worlds. And they did this with the buoying political lessons of writerly style—style as praxis, as a way of doing political thought by critical worldmaking. Berlant’s sentences do their work by asking much of us, by engaging us in the work as comrades, felt intimates, potential or actual friends. Their sentences are wound tight, portable, quick in their punch but longing for a slow unpack. One of the most striking examples is the first sentence of The Hundreds (2019), a co-writing experiment with anthropologist Kathleen Stewart that explored the powers of fragmentary juxtaposition: “Every day a friend across the ocean wakes up to suicidal thoughts.”

Holding together friendship, suicidal thoughts, and the many senses of wake across the abyss that is right here in the everyday, that sentence enacts political pedagogy through the powers of style in which Berlant continued to experiment and train. Berlant later shared, in an interview in the Journal of Visual Culture (2019), what they “learned” from the placement of that sentence, which makes what might be the last thing the first thing:

It is powerful to wake up the book with waking up thinking of dying. I thought if I were teaching this, I would probably spend 45 minutes on this sentence. Why? What does it mean to open up with an idea that the first thing might be the last thing, and that people live at the limit, and they try to dilate on what seeps or resonates through the pores of the limit?

The limit: that zone of impasse where we can’t go on and can’t let go, where optimism falters and shattering is unexceptional, yet where we might find ways of being in life without wanting and even refusing the world as given. Berlant opened thinking with the ends of lives and worlds as an altering life practice and a kind of porous holding environment for de-stigmatizing thinking about dying so as to confront the conditions that make that thinking necessary.

But this thinking with—enacted in shared writing and not just the classroom—was a method and not just an object. Asking “what does it mean?” and “what would it mean to think that thought?” to shift the otherwise stuck, Berlant committed to the uncertain project of thinking and writing with: in public, with us. Consider the framing of their research blog, Supervalent Thought, as a way “to learn how to write.” Their life writing exercised a pedagogy at the limit that worked to undo attachments to fictions of sovereignty by the public risk of thinking with what undoes us.

Lauren Berlant in a still from Shannon Walsh’s film Illusions of Control, 2019. Courtesy Shannon Walsh

Lauren Berlant in a still from Shannon Walsh’s film Illusions of Control, 2019. Courtesy Shannon Walsh

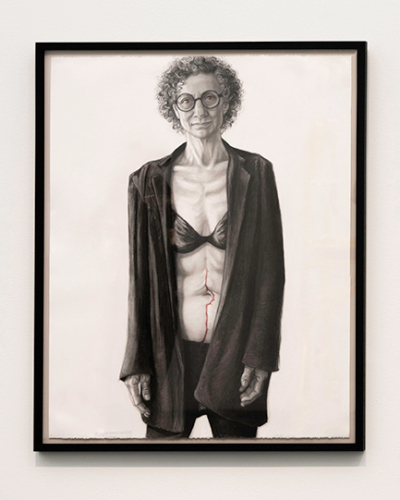

I woke up June 28 to learn that Berlant had died of cancer. First from Beth Freeman, whose article “Queer Nationality”—co-written with Berlant—still speaks to us about the collective life of desire after heteropatriarchal racial capitalism. How to lose the one who taught us how to live and write with losing? How to bear the unbearable and stay attached to life in a world that produces untimely deaths? We might turn to Berlant’s risk experiments—often co-labored in some way—in “crafting new realisms.” Take Riva Lehrer’s The Risk Pictures: Lauren Berlant (Standing Up), 2018, a mixed-media charcoal portrait of Berlant that withdraws from pain as spectacle to offer loss as medium. The jagged path of a red line marks the named “risk activity,” Berlant’s exposure of their surgical scar. And it stares back. Not unlike the eyes—the only other points of coloration on the otherwise gray field of the body—the scar redraws the red letters of stigma and trauma. Its unfixing look demonstrates instead the frank detachment that Berlant theorized as a style of attachment to rocking life.

Riva Lehrer: The Risk Pictures: Lauren Berlant (Showing Up), 2018, charcoal and mixed media on paper, 44 by 30 inches. Courtesy the artist and the estate of Lauren Berlant. Photo Nathan Keay

Riva Lehrer: The Risk Pictures: Lauren Berlant (Showing Up), 2018, charcoal and mixed media on paper, 44 by 30 inches. Courtesy the artist and the estate of Lauren Berlant. Photo Nathan Keay

As if unstoppable, Berlant wrote toward and not just about the forthcoming and the anticipated. Their planned trilogy in the making—On the Inconvenience of Other People (to be released by Duke University Press in 2022) and Humorlessness and Matter of Flatness (eagerly hoped for but whose status is not yet clear)—was to explore a different orientation to unrealizable fantasies of control and ordinary states of emergency that take post-melodramatic, deflationary forms of under-performative bodily comportment. Berlant kept going with the work of writing to sustain a life while radically questioning—as they did in a 4Columns review of Anne Boyer’s cancer memoir The Undying (2019)—the “carcino-desperation complex,” the “commons of suffering,” and the presumptive heroics of endurance.

In the absence of national mourning, Berlant reckoned with the Covid-19 pandemic and criminal abandonment by the state with a characteristically gripping re-figuration of urgent responsibility: “We’re living in a moment when national sentimentality and displays of compassion are muted because the government doesn’t conceive of itself as first responder,” they told a reporter for the Washington Post. They responded to the call for critical interventions into quarantine by narrating their dailiness with puncturing wit: “In the morning I yell ‘Smells!’” The ensuing still life interweaves the “treatment time” of cancer with the “streaming crawl” of living with Covid’s ordinary emergency.

But what are the forms for living our dying that also reckon with what makes a good life, much less a good death, unrealizable for most of us? In 2011, the Barnard Center for Research on Women in New York convened the Public Feelings Salon to honor the event of Berlant’s book Cruel Optimism, which theorizes the condition that keeps us attached to objects that wear us out, like the corrosive consumer versions of the good life and the good death. At the Center’s invitation to extend the Salon, I contributed the essay “Handle with Care,” addressing the impossible question of the good death raised in the book’s third chapter, “Slow Death.” Berlant led the way in the challenge of their response that survival includes the necessary, queer work of making a world in which something like the good death is possible by doing it together non-normatively:

Casid’s point, and mine in ‘Slow Death,’ is that survival includes dying, dying well: making good deaths that are a part of what it means to value life. When we care we have to think about what it means to value life, and to ask what it means to care about something, someone, some object/scene: it is to ask what we can learn from the relation of love and desperation, which is, after all, a political question.

The good death demands no less than the reorganization of the infrastructures of care for life. And, yet, we live our dying in the meanwhile anyway. And what are the forms for that? Berlant lived the discomfiting political question of the good death, converting that object into a scene—and holding open the door. Be in the room with it, they might say. Dive into the vertigo of the way they pose the question of not knowing who we will become in a crisis in the scene where they stand at the window in Shannon Walsh’s non-fiction film Illusions of Control (2019), shot spatially from the back and temporally behind their cancer diagnosis. Berlant here posits grappling with dying as integral to a refusal of the killing norm by helping each other imagine and enact ways of “being alive beyond the conventions.”

Berlant wrote their own epitaph in advance, and shared it. First in 2011 (on Supervalent Thought) as an address to the labor conditions that at best allow only tumbling—flailing revised later to look like a plan: “[W]hen it was only doing what you could do at the time (my epitaph) in an act of blind hope.” Later, published with the distance of the third-person in The Hundreds (2019), the epitaph became: “She did what she could do at the time.” Within conditions of co-authorship with Stewart, that epitaph and its “she” became capacious—a kind of “they,” even before Berlant changed their pronouns. The full iteration in The Hundreds offered it as a shareable worldbuilding praxis—a she with the give of an open, nonbinary, attachable, and plural theirs:

Then there are the people, my peeps, who turn their faces to the world to say this and make that because what they see is what they have to give. I want to call their mode of being “The New Frankness” and share with them my future epitaph: “She did what she could do at the time.”

In a subsequent interview for The New Inquiry, Berlant claimed that epitaph in the present tense:

[P]eople are looking hard for something from anyone who’s sustaining a thought, a pedagogy, an orientation toward resistance and attachment to life. This is why my epitaph is, “She did what she could do at the time.“

Yet their epitaph still shares the potential of a collective form for more than mere living on in the fray of our interdependence. In thinking with and after Berlant to imagine and enact ways of living our dying beyond the formaldehyde of the necropolis of settler colonial liberalism, by joining in the task of devising forms for Black, Indigenous, queer, and trans thriving, we might become a them worthy of their epitaph. They did what they could do at the time.

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/lauren-berlant-remembrance-jill-casid-1234599248