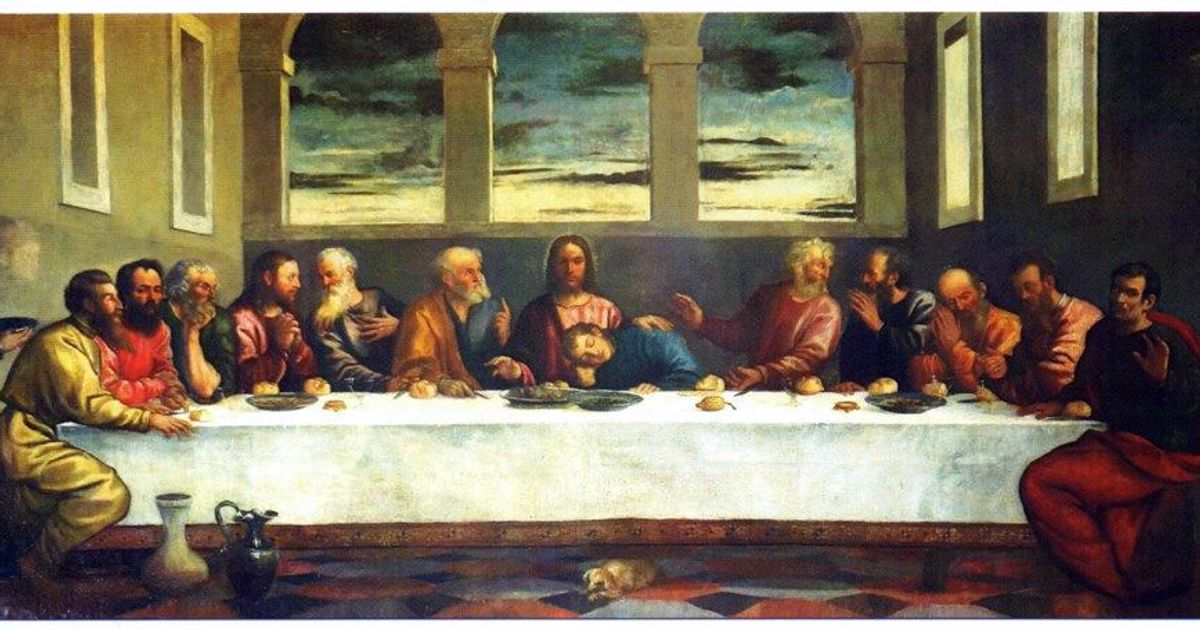

Who would have thought that you could discover a 16th-century Venetian masterpiece “of Titian” hiding under a pile of scum in a church in Herefordshire?

Yet that’s exactly what Ronald Moore, an expert on Italian Renaissance art, says he has done. For more than 100 years, The Last Supper languished in Ledbury Parish Church, to which it had been donated in 1909. But after his restoration effort, and the discovery of an inscription “TITIANVS”, Moore proclaimed this could be a work by Titian, his sons, or his school. It was accompanied by a letter from John Skippe, its former owner, in 1775. In it, he describes a purchase from a rich Venetian family of a monastic commission, the “best-preserved picture of Titian”. Together with the inscription and other evidence, this prompted Moore’s view that it came from Titian’s studio.

Moore may be right, but right now it’s just an opinion. The “Ledbury Titian” raises a question: who and what should we believe about the attribution of a work of art?

We seem to have an insatiable appetite for finding “masterpieces” and consequently may readily believe in “expert” judgment. But what is the value of expert opinion in the art world, anyway? And does it matter which expert’s view it is?

We don’t have to put a price on Moore’s opinion. At least, not yet. The public can still enjoy the work without the looming prospect of an auction sale to test his judgment in the commercial sense. But the art market abounds with instances where buyers have blown a decent proportion of the GDP of a small nation on a work of art they believe to be by a big name artist. A recent example is the sale of Sandro Botticelli’s Young Man Holding a Roundel at Sotheby’s New York auction in January, for a staggering $92m (with fees). It was last bought for a paltry $810,000 in 1982, after it had been handed down through several generations of a Welsh aristocratic family.

The exquisite quality of the portrait, thought by Sotheby’s to be one of Botticelli’s finest, could not be doubted. But Young Man Holding a Roundel has an incomplete provenance that apparently stops in the late 19th century. Unlike the Ledbury Titian (which at least has an accompanying letter), nobody can even be sure who commissioned the Botticelli. Because of this lack of documentation, some critics are still hesitant to attribute the work to Botticelli or to one of his school.

Attribution of authorship is based on numerous factors of which provenance is but one. It would be unreasonable to suggest you could have a reliable origin for everything that is centuries old when so much has intervened—war, natural disaster, economic failure, theft.

Expertise, or “connoisseurship”, also helps us to determine authenticity. In a painting, an expert will look at everything from the line and the brushstrokes, the structure, subject matter, materials, comparisons, and underpainting. Ideally, expertise is supported by a full provenance and historical record, to produce a reliable conclusion on authenticity.

Where provenance is incomplete, sometimes all we have to rely on are experts like Moore. But here there is another problem. You don’t need professional, scholarly or other qualification requirements to become an expert. If certain important people or institutions accept your authority, you’re in business.

Next comes independence. Since the start of the art trade incentives have existed to validate attributions. The Renaissance expert Bernard Berenson was supposedly infamous for his optimistic attributions of Italian Old Masters, which he allegedly sold to collectors at vast profit.

And experts are not infallible. While contemporaneous documents don’t change, experts’ opinions do. Authenticity is a fluid concept that depends on prevailing orthodoxies at a specific time. For example, three paintings by JMW Turner were shut away as fakes for 50 years until they were found to be genuine, including by the expert who first declared them inauthentic. And some works are destined never to be categorised as fake or genuine but to remain “maybe’s”, because we just don’t know.

Whatever the reliability of artistic scholarship and experts’ motivations, the desire for status enhancement is endemic. Wishful thinking often leads to blithe acceptance that a work is authentic just because someone highly placed in the art market says it is. And paying a price in the tens of millions of dollars, as in the case of the Botticelli, or eventually, if it is sold, the Ledbury Titian, can be as much to do with prestige as owning a beautiful work.

We are sometimes willing to overlook gaps in provenance, or disagreement between experts, simply because we want to believe in fairytales. We covet the sublime. Perhaps we are experiencing an existential watershed. Owning a little piece of a golden age that will never be replicated, only a fraction of which survives today, may be one panacea.

Noor Kadhim is an art lawyer at Armstrong Teasdale. Her blog can be found at www.theartvocate.blogspot.co.uk

Source link : https://www.theartnewspaper.com/comment/the-value-of-expertise