In less than a week Van Gogh painted a series of still-lifes of Sunflowers. Although they failed to sell during his lifetime, they would now be worth an unimaginable sum. Today the Sunflowers are arguably the world’s most instantly recognisable artworks.

It is less well known that Vincent painted four still-lifes of sunflowers in the Yellow House in Arles in 1888. The first, with three sunflowers, has always been hidden away in private collections. The second, with six flowers, was destroyed in a bombing raid in Japan during the Second World War.

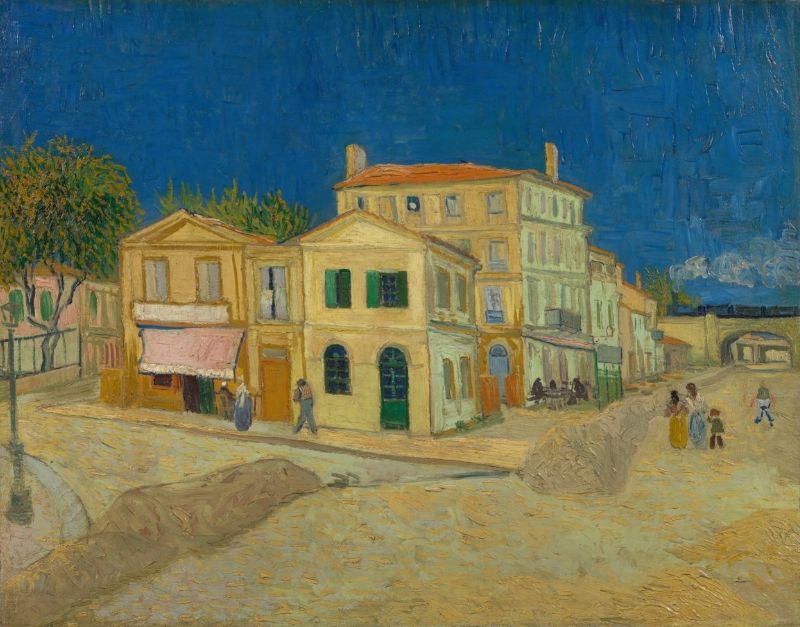

Vincent then went on to paint the two which would become famous: 14 flowers on a turquoise background (in the collection of the Neue Pinakothek, Munich) and 15 flowers on a yellow background (in the National Gallery, London). These were painted to decorate the spare bedroom at the Yellow House, to welcome the arrival of Paul Gauguin.

August—the month when sunflowers bloom and the anniversary of Vincent’s paintings—is an appropriate time to delve into these masterpieces. Here we present ten surprising facts: even those who really know Van Gogh will hopefully discover something new.

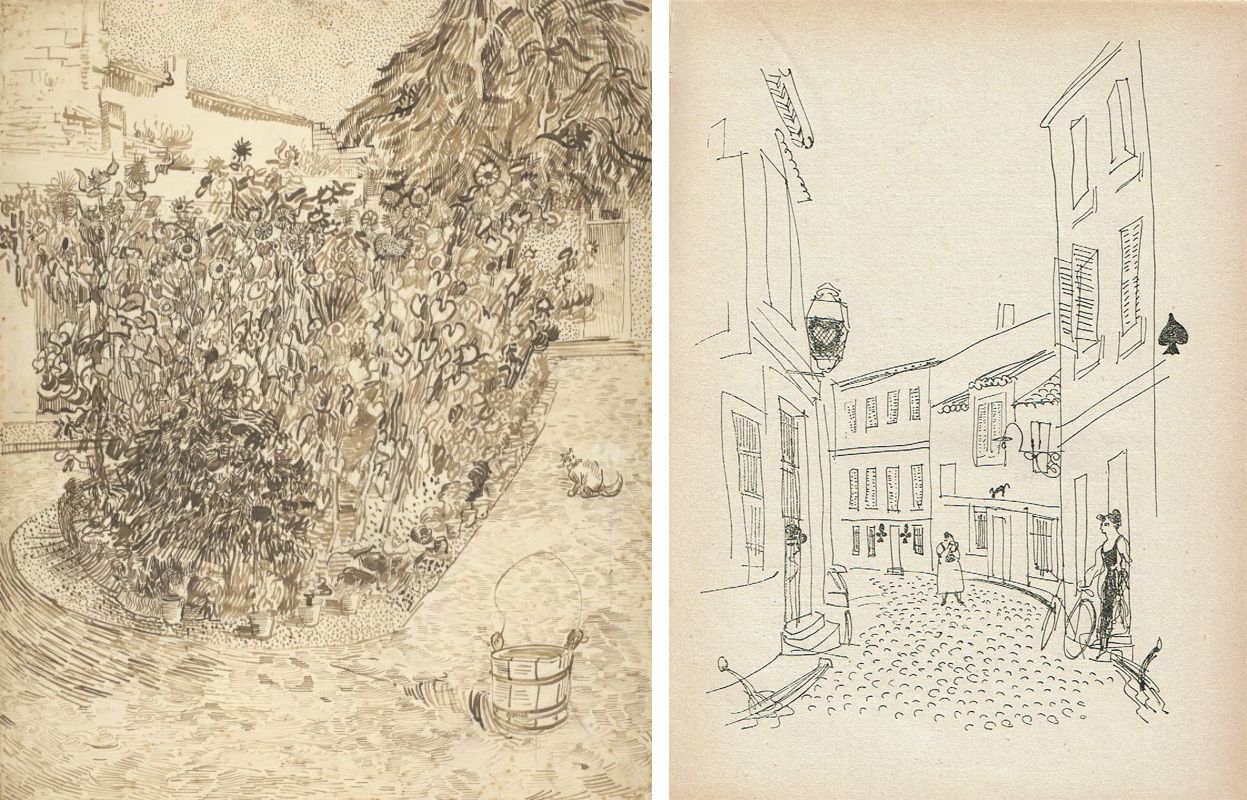

1. A week before starting on the paintings Van Gogh drew sunflowers in the garden of a bathhouse in the brothel quarter

Vincent made a delightful drawing of a garden bed bursting with soaring sunflowers (he also included a cat and added his tiny signature near the bottom of the wooden bucket). Writing to his brother Theo a week before tackling the four Sunflower paintings, he described it as “the little garden of a bathhouse”. Of the four bathhouses in Arles, the closest to the Yellow House was in Rue de Vers (now Place Marius Jouveau), in the then red-light district. This apparently tranquil back garden may well have been a haven behind a rowdy street. It is even possible that Vincent picked the sunflowers for his paintings in this very spot.

2. Vincent only turned to Sunflower still-lifes because of the wind and the rain—he needed to work in the cosy Yellow House

2. Vincent only turned to Sunflower still-lifes because of the wind and the rain—he needed to work in the cosy Yellow House

On 18 August 1888, two days before beginning the Sunflowers, Van Gogh complained there was “the devil of a mistral”—a fierce wind that blows down the Rhône valley. This made it difficult to keep a canvas on his easel. A few days later there was heavy rain. Vincent then planned to paint portraits, but again he was stymied. As he wrote to Theo: “I’ve missed some models that I hoped to have these past few days”. Unable to tackle portraits inside the Yellow House (his studio was through the green door), he turned to still-lifes.

3. Van Gogh did not actually paint the flowers in a pot

3. Van Gogh did not actually paint the flowers in a pot

Van Gogh liked to paint what he could see, so it is usually assumed that he placed his sunflowers in a pot in front of his easel. On a visit to Arles I bought a similar 19th-century rustic food pot in an antique shop and tried to place 15 sunflowers in it. The stems were much too thick and would not have fitted, but even squeezing in five and filling the pot with water would not have worked. The pot was not steady enough—and the heavy flowers would have toppled over. Van Gogh presumably had a similar pot in his kitchen-studio to serve as his model, but the 15 sunflowers were not actually placed in it (Gauguin’s portrait of Vincent making a later copy of his Sunflowers is a partly imaginative scene).

4. Why the crudely painted blue line?

4. Why the crudely painted blue line?

Van Gogh’s Sunflowers are so well known that we don’t usually look at them properly. But could I suggest that you focus on the blue line that separates the table and the background in the version with a yellow background. Unless it is pointed out, few viewers notice that the uneven and sketchy line has been painted just above the table and on the right side it is partly a double line. The table is also very slightly skewed, being higher to the left of the pot. The separate blue line across the pot is patchy, with a series of fairly straight rather than curved marks. All this is deliberate, not the result of clumsy brushwork. Van Gogh’s bold decision to include these crude blue lines breaks up the symmetry, adding yet more vibrancy to the composition.

5. Vincent celebrated the completion of his Sunflowers with a shopping spree

5. Vincent celebrated the completion of his Sunflowers with a shopping spree

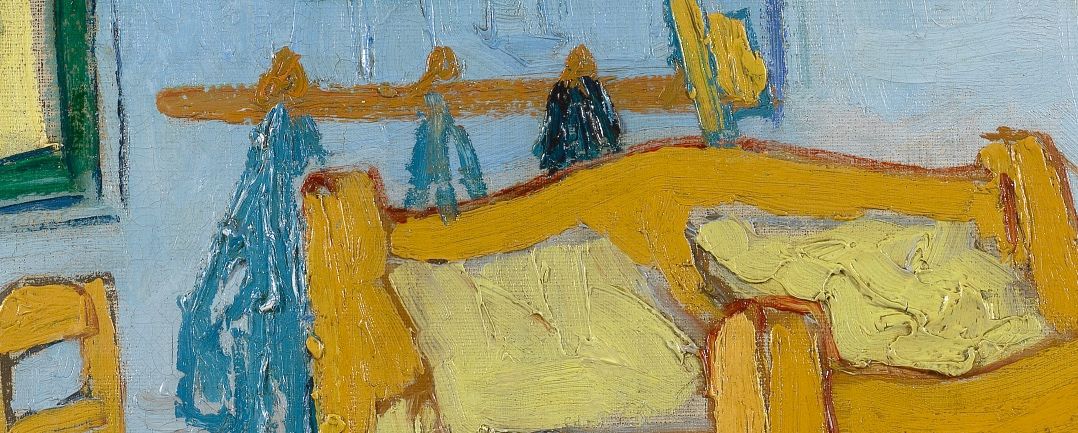

Van Gogh started his series of Sunflowers on Monday 20 August 1888 and finished on the Friday. He then relaxed by temporarily abandoning his studio for a shopping expedition in town. Although notorious for his shabby clothes, he returned with “a black velvet jacket of quite good quality for 20 francs” (a surprising purchase in the sweltering heat)—and a large yellow straw hat. Both items may appear to be hanging behind his bed in the painting he made of his bedroom two months later.

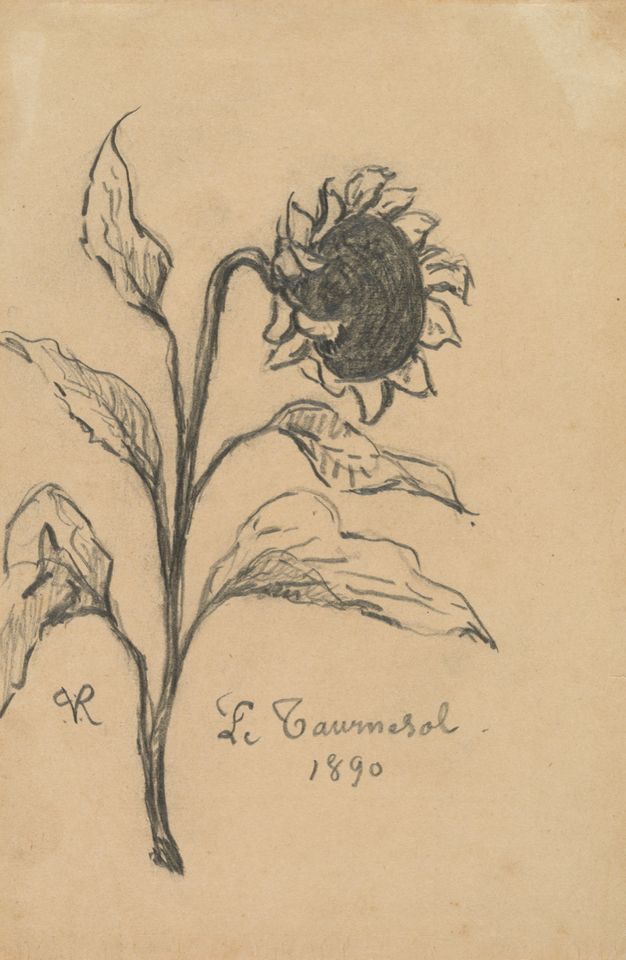

6. After Vincent’s suicide his doctor, Paul Gachet, drew a simple tribute—a poignant single sunflower

6. After Vincent’s suicide his doctor, Paul Gachet, drew a simple tribute—a poignant single sunflower

Dr Paul Gachet was at Van Gogh’s beside for the two days from 27 July 1890, when he shot himself to his death following two days later. Three weeks afterwards, Dr Gachet—an amateur artist—visited Theo in Paris, presenting him with a symbolic drawing inscribed “Le Tournesol” (The Sunflower). This poignant sketch has not been widely reproduced. That month, Dr Gachet planted sunflowers on the grave. For those close to Vincent, the flower that turns towards the sun had already become inextricably linked with the artist whose career was cut short in his prime.

7. A Van Gogh letter about the Sunflowers was discovered hidden in a book bought for a few francs from a bookstall by the River Seine

7. A Van Gogh letter about the Sunflowers was discovered hidden in a book bought for a few francs from a bookstall by the River Seine

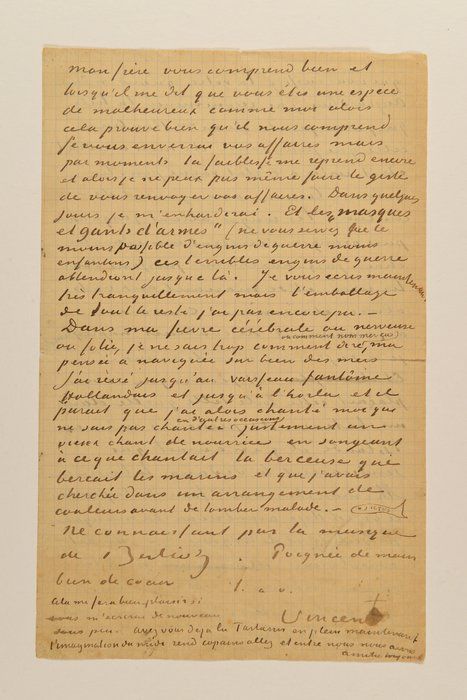

At a New Year’s Eve party I met a fellow guest who revealed how he and a friend had found a letter from Van Gogh to Gauguin, slipped inside a second-hand biography of Gauguin. In the letter Vincent writes to his friend: “The Sunflowers are Mine”—meaning that the blooms represented his forte. Such a discovery may sound too good to be true, but letter was authenticated by the Van Gogh Museum. Who tucked it into the book remains a mystery, but the earlier owner of the letter must have thought it would be a convenient place to store it, back in the early 1900s when it had little value. The lucky buyer of the book sold the letter to the Musée Réattu in Arles in 1984, turning a good profit—it went for £24,000. But prices of Van Gogh’s correspondence have soared and in 2012 (when the manuscripts market was performing well) another of his letters sold for £360,000.

8. Gauguin grew sunflowers in Polynesia as a tribute to his lost friend, we have the receipt for the seeds

8. Gauguin grew sunflowers in Polynesia as a tribute to his lost friend, we have the receipt for the seeds

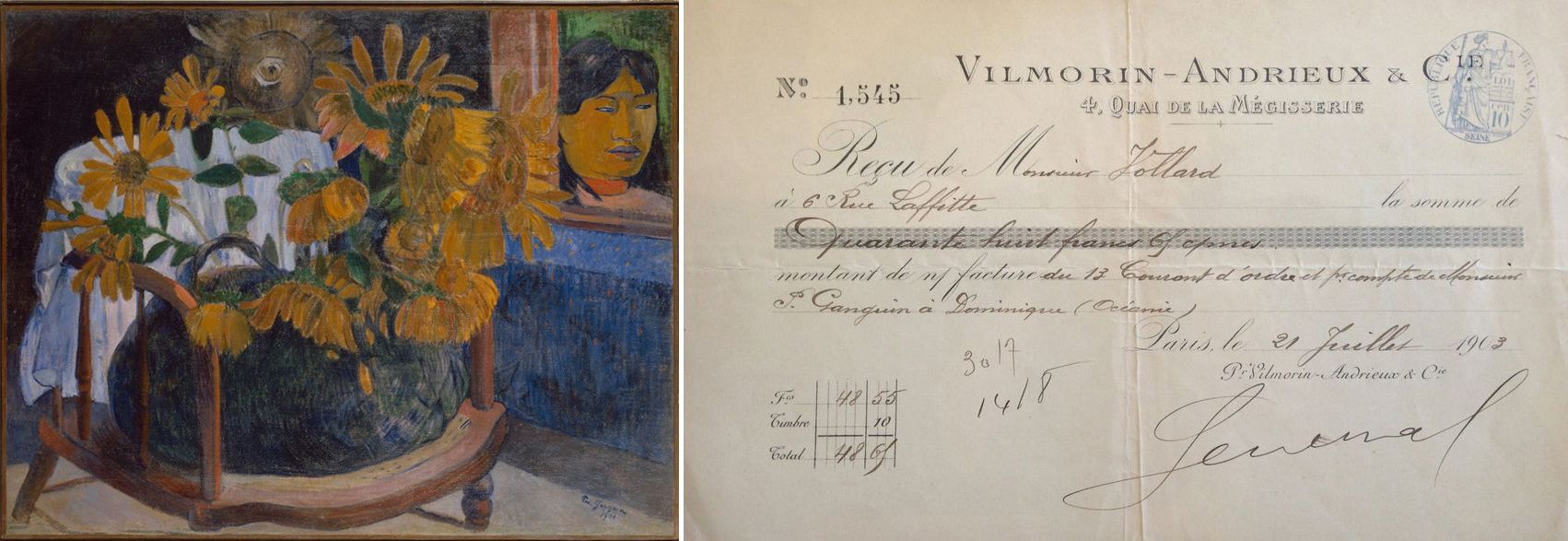

In 1901 Gauguin, then in Tahiti, painted four still-lifes of sunflowers resting on a chair—a salute to his long-departed friend. He had grown the flowers with seeds imported from France. Later that year, Gauguin set off for the remote Marquesas Islands. In March 1902, he wrote to his Paris dealer, Ambroise Vollard: “Please be good enough to send me by post the flower seeds mentioned on the enclosed list. Get them from the firm of Vilmorin, that is the place where one can be sure of getting fresh seeds.” By chance I found Vollard’s Vilmorin receipt, which had been misfiled in a Renoir archive and was sold by New York-based Heritage Auctions in 2013. Unfortunately, Vollard was tardy in paying Vilmorin, so when the seeds eventually arrived in the Marquesas in 1903 Gauguin had been dead for some weeks, struck down by syphilis.

9. Theo’s widow Jo Bonger fell in love with the artist Isaac Israëls—and lent him her Sunflowers

9. Theo’s widow Jo Bonger fell in love with the artist Isaac Israëls—and lent him her Sunflowers

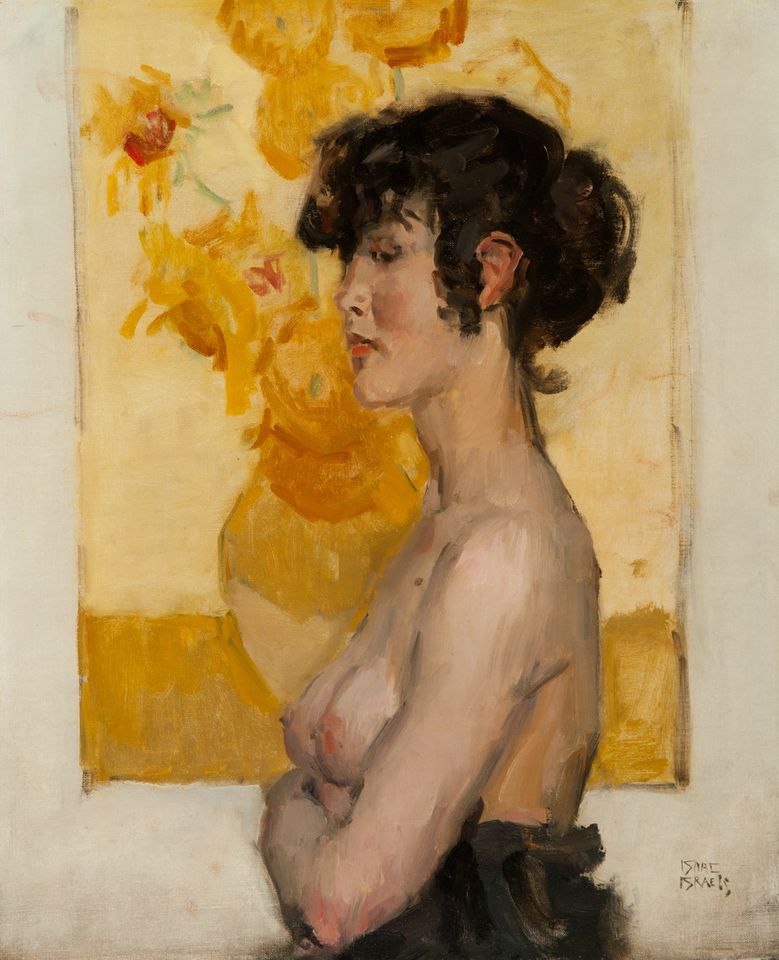

It has only recently emerged that Jo Bonger, Theo’s widow, had a short love affair with the Dutch painter Isaac Israëls in the mid-1890s. They remained good friends, and in 1918 she lent him the Sunflowers with a yellow background. Israëls hung it in his sitting room and included it in paintings with various models (but not Jo). Interestingly, the pictures by Israëls reveal that the Sunflowers was then enclosed in a plain frame—presumably the original one dating back to Vincent’s lifetime. In December 1889, when Theo was preparing the picture for an exhibition in Brussels, he followed Vincent’s wishes, adding “a white frame”. White frames were just becoming popular with avant-garde artists, who avoided fancy frames to emphasise their break with tradition. Unfortunately, the original frame on the Sunflowers was lost by the 1950s and the National Gallery now displays it in a fairly simple 17th-century, Italian golden frame.

10. Nazi leader Hermann Göring owned a Sunflowers—but it was a fake

10. Nazi leader Hermann Göring owned a Sunflowers—but it was a fake

Van Gogh was branded as “degenerate” by the Nazis and German museums were forced to sell off five of his paintings. But in private, Hermann Göring, Hitler’s deputy, was quite happy to enjoy a looted painting of Two Sunflowers. In 1942 he gave it as a Christmas present to his wife, the actress Emmy Sonnemann. They hung it in Burg Veldenstein, the medieval castle they had outside of Nuremberg. During the Allied advance in 1945, Göring sent the picture for safekeeping in the Nazi Alpine stronghold of Berchtesgaden. There, it was recovered by American troops and returned to its pre-war owner in Paris, the Paul Rosenberg gallery. Göring, who committed suicide just hours before he was due to be hanged in 1946, never realised that his looted Van Gogh was an extremely crude forgery.

• For more about the Sunflowers, see my book The Sunflowers are Mine: The Story of Van Gogh’s Masterpiece, recently out in paperback.

Martin Bailey is a leading Van Gogh specialist and investigative reporter for The Art Newspaper. Bailey has curated Van Gogh exhibitions at the Barbican Art Gallery and Compton Verney/National Gallery of Scotland. He was a co-curator of Tate Britain’s The EY Exhibition: Van Gogh and Britain (27 March-11 August 2019). He has written a number of bestselling books, including The Sunflowers Are Mine: The Story of Van Gogh’s Masterpiece (Frances Lincoln 2013, available in the UK and US), Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence (Frances Lincoln 2016, available in the UK and US) and Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum (White Lion Publishing 2018, available in the UK and US). Bailey’s Living with Vincent van Gogh: The Homes & Landscapes that Shaped the Artist (White Lion Publishing 2019, available in the UK and US) provides an overview of the artist’s life. His latest publication is the reissued book The Illustrated Provence Letters of Van Gogh (Batsford 2021, available in the UK and US).

• To contact Martin Bailey, please email: [email protected] Please kindly refer queries about authentication of possible Van Goghs to the Van Gogh Museum.

Read more from Martin’s Adventures with Van Gogh blog here.

Source link : https://www.theartnewspaper.com/blog/ten-surprising-facts-about-van-gogh-s-sunflowers-his-greatest-masterpiece