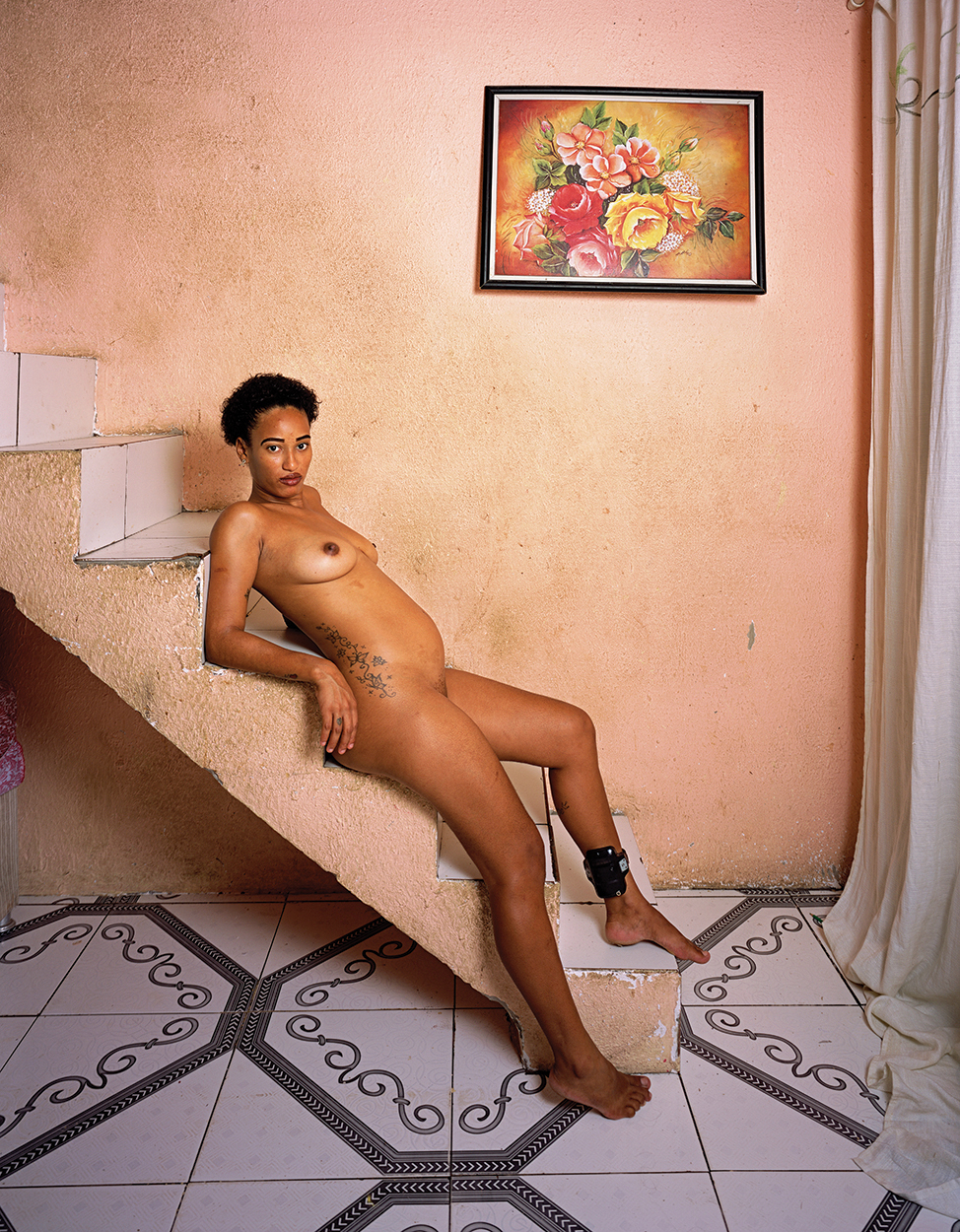

Deana Lawson: Daenare, 2019. Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles

Deana Lawson: Daenare, 2019. Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles  A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See by Tina M. Campt, MIT Press, 2021;232 pages, $29.95 hardcover. Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

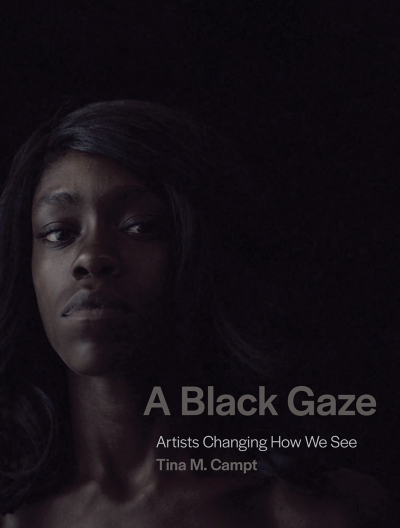

A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See by Tina M. Campt, MIT Press, 2021;232 pages, $29.95 hardcover. Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

The notion that Black art has been experiencing some kind of “moment”—as described, for example, in numerous published reflections on art trends in the tumultuous 2010s—has mutated into a condescending maxim. This “moment” is often referred to as an unprecedented groundswell of Black/African American cultural production, or, equally ahistorically, a renaissance. Both descriptors ignore how Black creativity has been part of the lifeblood of American art for centuries.

Sidestepping these simplistic ways of historically situating Black art and moving beyond mere questions of representation and identity, Tina Campt’s new book, A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See, due out in August from MIT Press, is a methodological offering, a theory of what Blackness brings to making and viewing art, and to perception in general. Campt meditates thoughtfully on eight contemporary artists and, along the way, models a positively disorienting approach to visuality, compelling us to think about the interplay between Black art and the ways we exist in the world. Rather than tethering racial identity to an essentialized mode of looking, in the domineering sense that “gaze” has typically connoted—as in film theorist Laura Mulvey’s 1975 explication of “male gaze”—Campt describes the Black gaze as a heuristic approach to visuality. Specifically, the Black gaze is an oppositional way of seeing, a rebellious looking in response to white attempts to stifle and eliminate Black life—a deliberate challenge to current social-political-aesthetic reality.

A Black Gaze is a kind of informal sequel to the author’s 2017 Listening to Images (Duke University Press), in which Campt, a professor of media and modern culture at Brown University, advocates engaging archival photographs of Black subjects through methods borrowed from sound studies. Her definition of sound in both books is expansive: in A Black Gaze, quoting musicologist Matthew Morrison, she describes sound as “a particular physiological manifestation of how we absorb certain frequencies,” focusing especially on embodied affective registers. Similarly, Campt is interested in how we come to see—not simply what we see—and this process includes senses beyond the ocular. Invoking the freedom of the Blackest musical genre, jazz, Campt creates an analytical framework for describing disruptive visual forms: ones that stop and start, that stutter step or flow smoothly, ones whose tones are rumbling and sonorous, and others you have to strain to hear. Using multiple senses, especially touch and hearing, the Black gaze “rejects traditional understandings of spectatorship by refusing to allow its [Black] subject to be consumed by its viewers.”

Campt gives the work of filmmaker Arthur Jafa as a prime example, citing the technique he terms “Black visual intonation,” which is a filmic embrace of unsettledness, unpredictability, and improvisation. In numerous videos—like Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death (2016) or The White Album (2019)—the artist pairs instrumentals with a montage of viral images of Black life: celebration, racial terror, and everything in between. His works thus make intimate contact between different trajectories and narrativizations of Black experience. Jafa’s are “haptic images,” a term Campt discusses in her 2012 book Image Matters, drawing on film scholar Laura U. Marks’s notion that haptic images “impl[y] making oneself vulnerable to the image, reversing the relation of mastery that characterizes optical viewing.”

The book has seven chapters—Campt calls them verses—each focused on the particular Black gaze of one or two artists. The first verse, “The Intimacy of Strangers,” is devoted to Deana Lawson’s photographs. The distinctness of the Black gaze emerges through the artist’s use of confrontation: she forcibly transmutes the audience from passive lookers to active witnesses. “Lawson’s giant prints meet you eye-to-eye,” Campt writes. Her unflinching portraits of Black families in their homes usually contain a returned gaze “that invert[s] the normal rules of spectatorship and spectacularity.” The photographer’s Black gaze “twin[s] the respectable with the profane” without establishing a moral order or hierarchy. For Campt, Lawson’s work presents what bell hooks calls an “interrogating gaze,” because her sharp photographs often bring the viewer unsettlingly close to unnamed Black people and their private, domestic spaces, forcing us to interrogate the impulse to look away from her vibrantly colored and sometimes too sharply detailed shots of diasporic Black life.

Luke Willis Thompson: autoportrait, 2017, video. Photo Andy Keate/Courtesy Chisenhal Gallery, London

Luke Willis Thompson: autoportrait, 2017, video. Photo Andy Keate/Courtesy Chisenhal Gallery, London

The work of Luke Willis Thompson, a New Zealand–based artist of European and Fijian descent, illustrates the capaciousness and fraughtness of the Black gaze. Campt argues that Thompson’s mixed non-Black racial identity coupled with his artistic treatment of Black people—most notably of Diamond Reynolds, the Minnesota woman who livestreamed the bloody aftermath of the police killing of her boyfriend, Philando Castile, in a car seat beside her—demonstrates that “Black gaze” does not designate solely the way Black people see. The title of Thompson’s 2017 film, Autoportrait, is a synonym for self-portrait, and the work was born from his desire to create a “sister-image” to the cell phone horror that first made Reynolds known to the world. The resulting work is a 9-minute black-and-white film in which the camera fixes tightly on Reynolds’s upper body. There is a saintliness to her likeness: she’s shot from below, and the soft lighting creates an almost dreamlike effect. The film would have been impossible to make without her active participation, but in it, Reynolds does not speak—a controversial decision considering the historical silencing and erasure of Black women. Elsewhere in the book, however, Campt writes about the sound of quietness as distinct from silence. She interprets Reynolds’s posture and contemplative expression as an externalization of her interiority: “prayer, a meditation, or an internal monologue made manifest.”

Despite the fact that Reynolds’s survival and dignity are the subject of Autoportrait, groups like the curatorial collective BBZ London have criticized the work as an aestheticization of Black suffering by a non-Black artist who stood to profit from Reynolds’s experience: the film got Thompson nominated for the Turner Prize the following year. Thompson has called himself “a Black artist, albeit not of the African Diaspora,” and Campt takes this self-description seriously. British curator and art historian Aurella Yussuf, however, locates Thompson’s racial identification within the context of political Blackness, which can include various non-white people under a banner of racial solidarity. In her essay “White Skin, Black Masks” for the online journal Arts.Black, she describes the tension behind the white-passing artist’s exploration of what he calls “bodies ‘readymade for violence.’” Although Thompson names Reynolds as a collaborator, Yussuf maintains that the film “remains a voyeuristic exercise in exploring oppression through the intrusion on a Black woman’s grief, without meaningfully conveying how the audience is complicit.” Campt nevertheless considers Thompson’s adjacency a critical vehicle for unifying Afro-descendant communities with Indigenous peoples of the Pacific through a shared historical frame of global imperial domination. She maintains that the Black gaze is a “viewing practice and structure of witnessing that reckons with the precarious state of Black life,” an artistic ethic as opposed to an artistic genre with a singularly common aesthetic trademark or prescribed racial-ethnic identity.

Okwui Okpokwasili and Peter Born: Sitting on a Man’s Head, 2020, performance; at Danspace Project, New York. Photo Tony Turner/Courtesy the artist

Okwui Okpokwasili and Peter Born: Sitting on a Man’s Head, 2020, performance; at Danspace Project, New York. Photo Tony Turner/Courtesy the artist

Refusing simplistic depictions of Black life, the Black gaze can also force a production of slowness as a kind of ethic. In the verse “The Slow Lives of Still-Moving-Images” about photographer Dawoud Bey and performance artist Okwui Okpokwasili, Campt argues that both artists “slow down our encounters with blackness” in order to “intensify our understanding of the precarity of Black life.” This compels us to pause, register, and attend to the needs of the Black living and dead. Okpokwasili’s Sitting on a Man’s Head, first presented at the 2018 Berlin Biennale, channels the collectivized energy of Igbo women’s rituals for shaming men who’ve caused harm, which involves embarrassing him by singing and dancing outside his home. The semi-choreographed, four-hour performance—in which participants and performers alike walk and move slowly behind a translucent wall—is durational, just as the 1929 Woman’s War in eastern Nigeria was a protracted two-month-long expression of the social grievances enacted by thousands of women against colonial Nigerian society. Okpokwasili’s work memorializes twentieth-century African feminism through slow, deliberate movement.

Meanwhile, in his 11-minute, single-channel video, 9.15.63 (2013), Bey’s camera traces a drive similar to those that Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, Addie Mae Collins, and Cynthia Wesley experienced on their way to the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham on the day it was bombed, their last day—September 15, 1963. His camera lingers on foliage, the clear blue sky, and other ordinary details of the route, as well as four familiar community spaces: a diner, a barbershop, a beauty parlor, and a classroom, all empty because patrons and workers alike would have been in church that morning. Listening to these somber images, Campt argues, what we hear is not silence: it is the weighty sound of quietude. Quiet presents an opportunity to observe the relatively hidden frequencies drowned out by the cacophonous racket of everyday anti-Black life.

Stills from Dawoud Bey’s video 9.15.63, 2013. Courtesy Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago, and Sean Kelly Gallery, New York

Stills from Dawoud Bey’s video 9.15.63, 2013. Courtesy Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago, and Sean Kelly Gallery, New York

The most compelling implications of Campt’s Black gaze inform art criticism. The author details the labor of viewing that the Black gaze demands, describing how she spends most of her time writing to artworks. She writes to works “about the feelings they solicit, the forms of discomfort they evoke, the emotional work they require and often demand, and the potentially transformative effects they have when we allow ourselves to inhabit those feelings and responses.” Because anti-Blackness doesn’t affect white critics personally, it’s clear they can only give the machinations of and artistic reckonings with anti-Blackness certain types of thought; looking and reacting, Campt shows us, are only two of many ways of perceiving and knowing.

The Black gaze feels like an antidote to mainstream orthodoxy. It is a relation to art that seeks to transcend and refuse easy assimilation of Black art into the standard colored paradigm of representation, diversity, and inclusivity. As a writer primarily interested in Black/African/Afro-diasporic art, I have never been able to think about Black art without becoming entangled in my own subjectivity; I cannot write except from an embodied affective position. Unfortunately, I sometimes feel ashamed of this: it feels misplaced, like improper criticism that defies long-existing tropes and conventions of the impartial observer. But Campt’s Black gaze offers holistic modes of criticism, bringing her readers beyond mere detached, “objective” responses written from a distance. Campt says the book is about how visual artists are changing how we see Blackness, but perhaps more compelling is the slow seeing and sensitive writing about art that she models.

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/aia-reviews/tina-campt-black-gaze-1234601790