Jia Zhangke: Ash Is Purest White, 2018, film, 2 hours, 21 minutes.

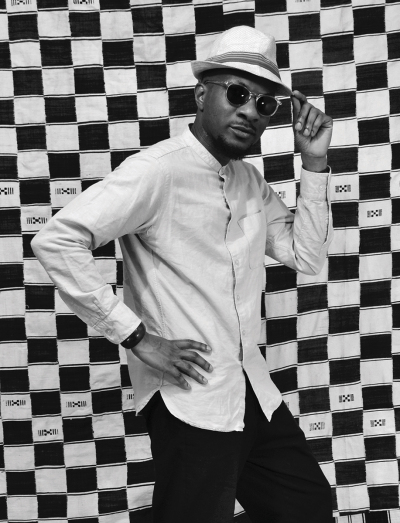

Jia Zhangke: Ash Is Purest White, 2018, film, 2 hours, 21 minutes.  Portrait of Teju Cole. Courtesy Teju Cole/Malick Sidibé Studio

Portrait of Teju Cole. Courtesy Teju Cole/Malick Sidibé Studio

I have been especially busy this year as I worked on finishing two books. Black Paper had a long gestation period because it includes essays from a span of many years. In it, I contemplate shadows and darkness—and, of course, the color black—all of which have strongly positive aspects for me. Darkness, for example, can be used as a form of protection in the wild. Ultimately, these are all essays that emerged in response to Donald Trump’s presidency. But they’re not about Trump. They’re about you do when the world is knocked upside down. And they pick up on an ongoing discussion of race. Some Black people may have black skin, many have brown skin, and some have light skin. Blackness has become a metaphor for a certain kind of societal categorization—one that I believe deserves to be given its full positive due.

My photobook Golden Apple of the Sun was an intense pandemic project. But it includes one of the longest essays I’ve ever written. It reflects on domesticity, food, and the personal connection to my own kitchen through a historical lens.

Yanyi’s volume of prose poems The Year of Blue Water [2019] is very intentional and emotionally precise. The book addresses themes of healing, solitude, trauma, ordinary life, community, death, and transition. “Womanhood is the country I come from,” he writes, expressing this great recognition that being a woman gave him something for a while before his transition. Everything is sort of sublimated in this gorgeous yet plainspoken voice. Its overwhelming impact is its humanity.

The London Review of Books podcast recently featured the young American writer Jesse McCarthy on his book Who Will Pay Reparations on My Soul? [2021]. He’s a subtle yet thoughtful essayist who’s thinking through problems, most having to do with race in America. In an economy where everything can be bought and sold, McCarthy and LRB’s US editor Adam Shatz talk about whether putting a dollar amount on reparations disposes of slavery as a deep historical wrong. One of the most striking points was McCarthy’s idea that if there’s anything good in this country, Black people have already contributed to it. Black Americans cannot afford the luxury of losing hope here, because they don’t have a place to return to—this is their home.

Sheet music of Julia Perry’s 1960 composition Homunculus C.F.

Sheet music of Julia Perry’s 1960 composition Homunculus C.F.

Julia Perry was living above her father’s medical office in Akron, Ohio, in 1960 when she wrote Homunculus, C.F. for ten percussionists. It’s a marvelous piece by an almost forgotten composer. Earlier this year, I curated a musical program for the Orchestra of St. Luke’s in New York. It was too difficult to put this piece together during a pandemic, but at least I got to spend more time with it. Perry’s work is not programmed much, but I think it deserves to be heard next to that of more prominent modernist composers. Perry was immersed in the history of music and knew what she wanted to say. When times are tough and we encounter something that is serious and well done, it tells us that culture is not shallow.

I recently read Deborah Levy’s autobiography The Cost of Living [2018]. At this stage in my career, I look for writers who are not just telling a story but also writing really well. Levy’s sentences just sing. They’re not very showy, they’re not very elaborate, but there’s maturity in her voice. She writes about a South African woman living in the United Kingdom who has just split up with her husband, experienced the death of her mother and the loss of her older daughter leaving for college, and is trying to write while caring for her younger daughter. There’s an emotional precision when a writer is both skilled and careful.

I really admire Jia Zhangke’s films, which often criticize local corruption and violence as part of an indirect criticism of the power structure of the Chinese Communist Party, but are also deeply humane. Ash Is Purest White [2018] follows a woman and her small-time gangster lover in a remote industrialized province of China. She goes to prison to protect him, but by the time she is released, he’s no longer a gangster and no longer interested in her. Jia really questions what it means to have sacrificed yourself for a concept that doesn’t exist anymore. It seems like this film had a smaller ambition than some of his other work. But the director’s rhythm and timing immerse the viewer in a different world.

—As told to Francesca Aton

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/interviews/teju-cole-sightlines-creative-precision-1234601921