Meghann Riepenhoff

Meghann Riepenhoff

Artist Eric William Carroll describes cyanotypes as the “photographic versions of finger painting: They’re tactile, child friendly, and yield immediate satisfaction.” Watching the process unfold, he says, “is equal parts magic and nostalgia.”

A variety of camera-less photograph, the cyanotype was invented in 1842 by astronomer and scientist John Herschel. Some of the best-known examples of cyanotypes are those made by British botanist Anna Atkins (1799–1871); Herschel was a family friend who taught her the technique. Atkins used cyanotype printing to produce accurate images of her botanical specimens, and her 1843 book, Part 1 of British Algae—thought to be the first book of photographs ever made—pioneered photography as a medium for scientific illustration.

Today, many cyanotype artists still make photograms, as Atkins did, by laying their subject directly onto emulsion-covered paper and exposing it to light. Others, like Angolan-born, Milan-based artist Délio Jasse, or German artist Ulf Saupe, create film negatives that they place on the paper before exposing it.

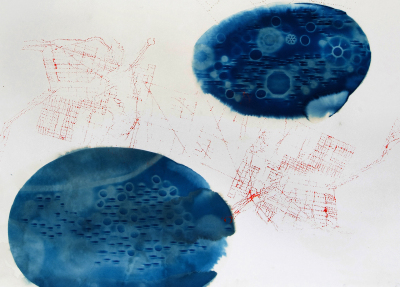

Eric William Carroll

Eric William Carroll

The base chemicals for creating cyanotypes are potassium ferricyanide and ferric ammonium citrate. The artist mixes those chemicals together into a UV light–sensitive emulsion and then, working away from natural light (an incandescent light is fine), paints it onto a surface. Usually this is paper or fabric, though cyanotypes can be made on anything that will stand up to the developing process. Pretreated papers are also available.

Once the emulsion has been applied and left to dry in a dark place, an object or negative is placed on the paper (a piece of glass helps keep it flat against the surface) and the paper is exposed to sunlight or light from a UV bulb. Exposure time will vary depending on the light, but when the emulsion starts changing color from yellowish green to greenish blue, the print is ready to be developed in a water bath. After being rinsed for a few minutes in water, the emulsion will turn a deep Prussian blue where it was exposed to light, while the unexposed emulsion will wash off, leaving white paper.

Initially, Saupe used sunlight when making his cyanotype prints, but he quickly found that by the time he’d painted his paper with emulsion, what had begun as a clear sky might have clouded over. “Exposure times change so much,” he says.

Ulf Saupe

Ulf Saupe

To get around the problem, Saupe now works in his studio with UV light tubes, which give him more control over the process. He often adds a little oxalic acid to his emulsion to achieve darker blues and clearer highlights, and he sprays newly washed prints with hydrogen peroxide to further deepen the color.

Saupe makes his negatives with Ulano film and prints on Canson or Arches paper. He has this advice for anyone getting started with the medium: “Always work clean and take care of your equipment. Also, choose the right paper.” The paper should be heavy enough to hold up after being washed in water, and—unless you want a particular effect—not so rough that the details of the print are obscured.

Seattle artist and designer Ellen Ziegler discovered pretreated cyanotype paper 20 years ago when looking for projects to do with her young daughter. It was easy to put leaves and other objects on SunPrint paper and then expose it outside. And the results were often stunning.

Ellen Ziegler

Ellen Ziegler

Ziegler makes prints from “a large collection of translucent and transparent objects: glass doorknobs, clear marbles, plastic shoulder covers that our grandmothers used to protect their clothes in the closet,” she tells ARTnews. “Also, dried cat grass with the dirt from the pot still attached. A cello. A transparent plastic raincoat.”

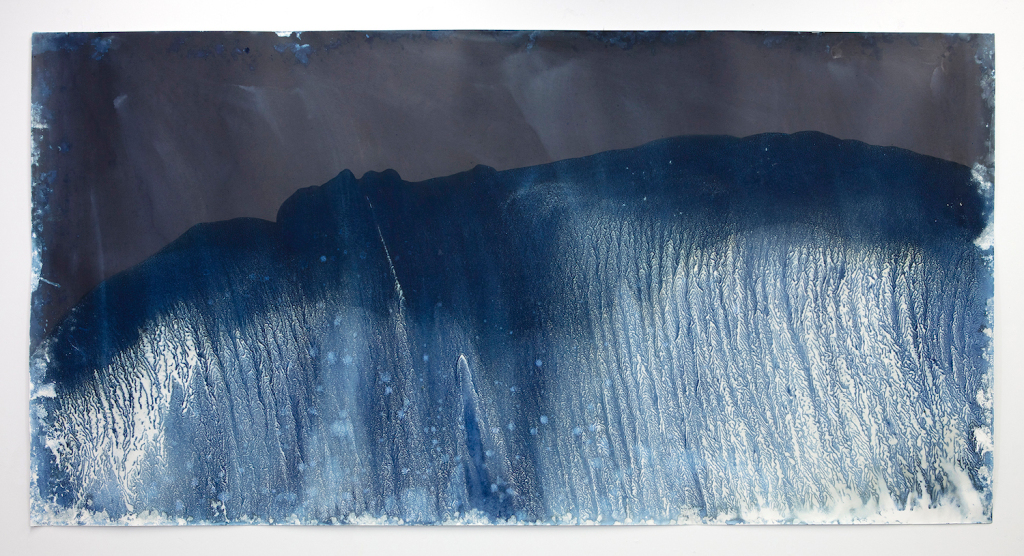

Through the pandemic, Meghann Riepenhoff, in collaboration with her husband, has been making a cyanotype each day in the same spot in their garden on Bainbridge Island, Washington. There are now more than 400 prints. Though the medium’s unpredictability may be a problem for people who want consistent results, Riepenhoff relishes it. As with any medium, she says, “the most interesting images will come when someone finds their own way to use [it].”

Meghann Riepenhoff

Meghann Riepenhoff

Riepenhoff’s images of ice, sand, rain, and snow are inspired by the work of British photographer Susan Derges, who “pushed the boundaries of what a darkroom is,” submerging photographic paper in rivers at night and using a flashlight and the light of the moon to expose it. Riepenhoff, too, sees the “landscape as a studio.”

Carroll also works outdoors, capturing the shadows of trees in the woods around his Asheville, North Carolina, home. To make the works, Carroll uses chemicals from Photographer’s Formulary, Bergger paper, and a brush specially made for resin work. For him, one of the most exciting things about cyanotypes is that there are so many possibilities still to be explored: “We’re largely still putting [emulsion] on paper. What happens if we paint a building with it? Expose it to video? Put it on the bottom of our shoes and walk around on a canvas? Even though it’s nearly 200 years old, the medium is still in its infancy.”

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-news/artists/how-to-get-started-making-cyanotypes-1234602654