The 11 September terrorist attacks in New York and outside Washington, DC, changed life in America irrevocably. As well as having long-ranging consequences for the country’s politics and national security—the US invaded Afghanistan in October 2001, after all, because the Taliban refused to turn over the Al Qaeda leaders who were behind the attacks—the events elicited artistic responses that reverberate to this day. On the 20th anniversary of 9/11, The Art Newspaper asked several artists to reflect on that day, and what impact it had on their work.

The morning that two hijacked planes hit the World Trade Center towers on 11 September 2001, a gentle breeze was blowing southeast, the New York artists Mike and Doug Starn recall. Their Brooklyn studio is in an area overlapping the Red Hook and Carroll Gardens neighbourhoods, a mile and a half from the World Trade Center, and the work papers of many of those who were killed in the terrorist attack began landing in the street, along with mail carried aboard one of the planes.

At the time, the artists, twin brothers, had been creating works of art incorporating leaves falling from trees. “When the papers were falling all around the studio, like massive amounts of litter, [we] had to go pick them up,” the Starns recount in an artists’ statement. “They belonged to someone—[we] need to help them, these are somehow vicariously part of the people who died, we can’t leave this just like trash.”

The shock of 9/11 and the ruminations that followed led them to create the series Fallen. “We coated the papers with silver gelatin and printed photographs of leaves; the papers fell from the sky like leaves in the autumn. Leaves are the living lungs of trees, soaking up the sun and building the trees with that light,” the artists say, adding, “Through our process we hope[d] to see the life and the death within these papers.”

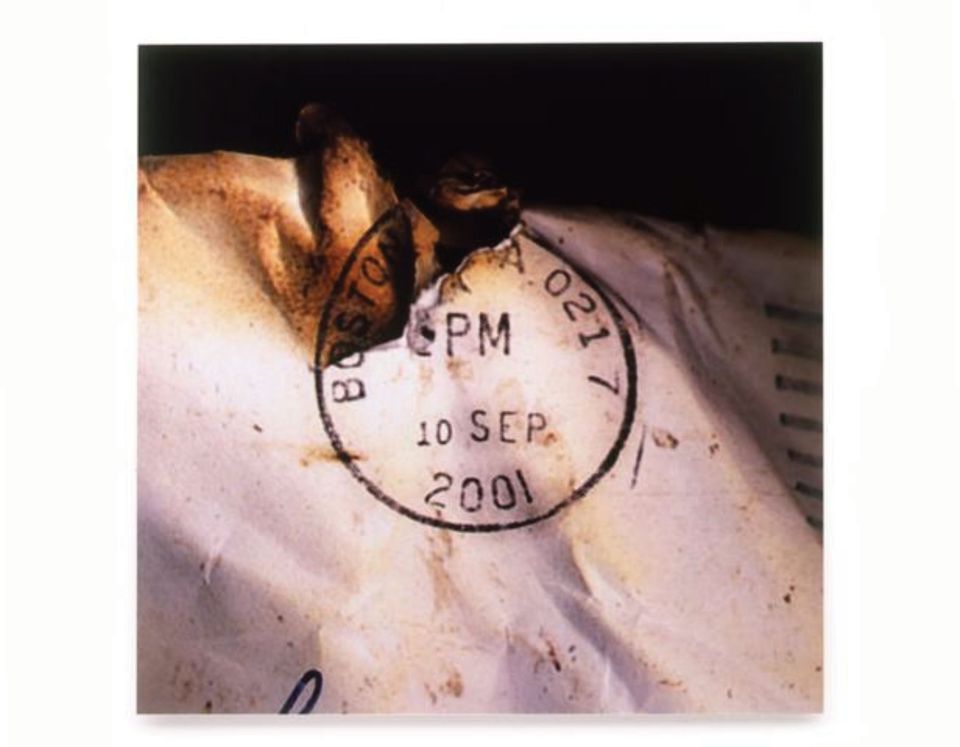

They particularly remember a letter mailed from Boston that was to be delivered to Los Angeles: “This letter’s postmark, on the last day of innocence, the last day we thought tomorrow would be pretty much like yesterday, seems to relate the ease with which the passengers boarded that plane on the morning of the 11th, and the horror of their fate.”

Looking back to that fateful day in 2001, Mike Starn sees an inexorable trajectory to the political and cultural situation that America faces today. “It’s clear the terrorist attack was a huge shock to the system and put opposing ideologies into motion—right-wing nationalism sunk to a new low of cynical and abusive Trumpism, while a more open, even progressive, humanism spread,” he said in an email. “For us [in] the [work of art], featuring the postmark from Boston, 10 September 2001, Doug and I see what looks like the last day of a child-like innocence for America.”

“Possibly it was a greater shock for white Americans, who had never been made to feel vulnerable at home”– unlike those who died in the 1921 Tulsa Massacre of Black citizens in Oklahoma, for example, Starn adds. Now, he notes, white Americans have joined Black Americans in expressing outrage over the police killings of Black men including Eric Garner, George Floyd and others.

The painter Ford Crull was in his studio on Broadway below Chambers Street when the first plane struck the World Trade Center’s North Tower.

From City Hall Park a few blocks away, he saw the second plane ram the South Tower. “It wasn’t a raucous crash. It didn’t sound that way. It wasn’t that loud. It was as if the building just absorbed the plane,” he said. The sky, he recalled, was surreal. “There were sheets of 8½ by 11 paper everywhere, just floating around in the sky and coming down like rain.”

With the collapse of the buildings, “a thunderstorm of ash and cloud pervaded everything as if it were in the Dustbowl era,” he said. “When that cleared, the site was absolutely deserted.”

Police first rushed Crull and anyone else in the area onto boats to New Jersey, but he took a PATH train back to Manhattan and walked downtown through security points. Crull also took pictures. “I had a Nikon, which had a charger on it. But the problem was finding a place to recharge it. Somehow Reade Street Pub and Bar still had power.”

His photographs of 11 September show scenes of empty desolation—some framed in a white and brownish haze, one with the New York Stock Exchange standing behind barriers in the distance. “I was there with my fake badge until the National Guard kicked us all out,” Crull says.

“For weeks it was hard to breathe, that smell you never forget—mucky, metallic, burnt rubber, like when I used to work in the steel mills.” Crull recalls. “Every now and then, when I smell it, it still reminds me of 9/11.”

“The first painting that I did after 9/11—it’s very red, with the title at the bottom, All That Matters. I did have a show in mid to late November [2001] in New York, and that was, interestingly, the only painting that sold. It looks halfway between a building and a person’s torso,” says Crull, who usually works in abstraction.

The legacy of the war on terror

Like so many Americans, the artist and geographer Trevor Paglen recalls exactly where he was when word arrived that two planes had crashed into the World Trade Center: in a courtyard at the Art Institute of Chicago, where he was enrolled as a graduate student working towards an MFA degree. A friend came rushing out of the building to deliver the news. “We stepped back into a classroom and kept on trying to refresh CNN’s website—the internet was so much slower then—and they eventually cancelled class,” he recalls.

At the time, Paglen was focusing on a series of works exploring the American phenomenon of mass incarceration by harnessing images, video and audio recordings he compiled during visits to California prisons. After the 9/11 attacks prompted the US to launch its so-called “war on terror”, he expanded his sights to scattered “black sites”, a network of clandestine prisons created abroad for suspected terrorists by the CIA, where torture was routinely practiced to elicit information.

“We travelled all over the world trying to find those black sites and to understand the impact on politics and culture,” Paglen says, referring to Torture Taxi, a 2006 book he wrote with the journalist A.C. Thompson. Harnessing his astronomy expertise, Paglen produced thousands of photographs, many of them taken at a range of more than 20 miles, of military and intelligence facilities that were off limits to civilians, such as the Salt Pit prison east of Kabul in Afghanistan, shot in 2005.

Another series homed in on the signatures of fictitious people—for example, a person listed “as having been born in the 1960s but with a Social Security number created in the 1990s”—on registration documents for shell companies created by the CIA to bypass international conventions restricting operations of the US military. He also photographed CIA officers using fake passports, unmarked aircraft intended to transport detainees, artefacts from American military culture and sites such as Area 51 in southern Nevada, a highly classified testing and training range for the US Air Force.

“I wouldn’t say that the attacks had a big effect on my thinking so much as the amorphous and ambiguous war on terror and the authorisation of military force giving the president unlimited power to wage war,” Paglen says. “You start to see institutions change, the norms change, and the war on terror having a huge imprint on everyday life and institutions in the US”—including the expansion of everyday mass surveillance. “I think it not only had an impact on my worldview, but on the world.”

The recent victory of the Taliban, leading to frantic attempts by thousands of Afghan citizens to flee, has been “heartbreaking”, Paglen says, noting the help he received during his investigative odyssey there. “I feel for the people I worked with.”

‘Not all art is therapy’

The painter Keith Mayerson, who was living downtown in SoHo and teaching at New York University at the time, remembers heading to lead a freshman drawing class soon after the planes hit, “overwhelmed with shock”, and found his students equally bewildered. “I told them that ‘not all art is therapy, but I don’t know what else to do but go out and draw this,’” he says. “We walked briskly to Washington Square Park, in clear view of the towers, and just as my students got their sketchbooks out, the first tower fell.”

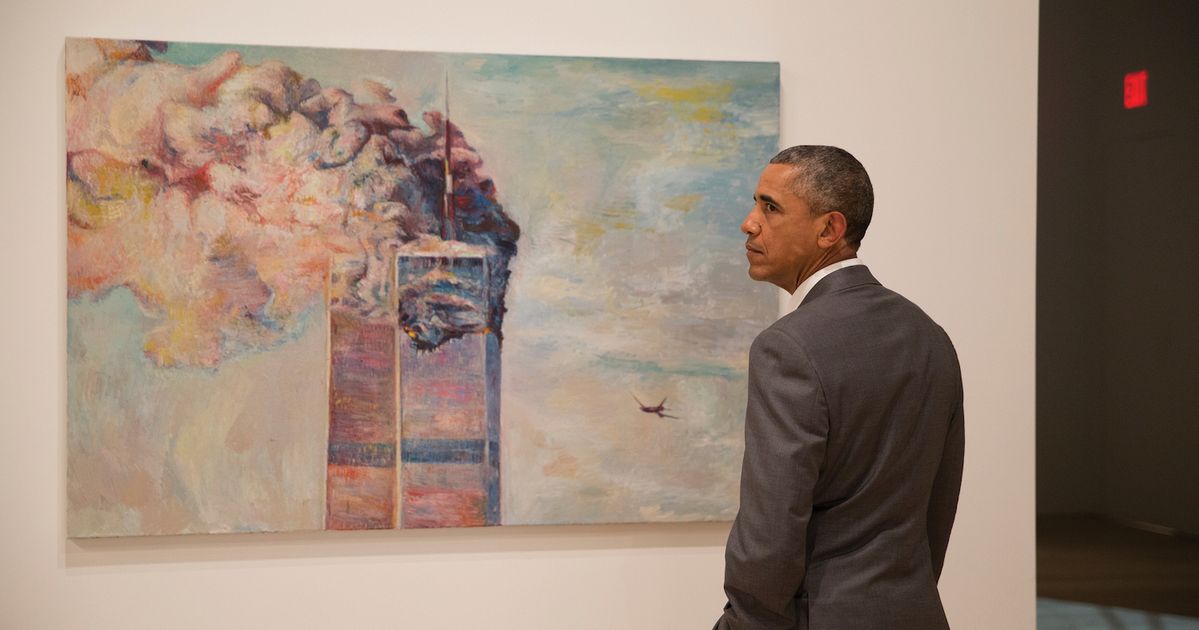

“For several years, I would paint 9/11 via allegory: Jimmy Stewart barely hanging on in [the film] Vertigo; the King Kong remake from the 70s, where he fell from the towers; Spiderman trying to save them all,” Mayerson added. “But I had persistent nightmares of the people falling and jumping from the towers for years.” It took around six years for the artist to directly paint about the day, drawing on images from newspapers his father had saved. The 2007 work 9-11 showing the One World Trade Center tower on fire, now in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art, “was the hardest painting I had ever done in my life”, Mayerson says. The piece was included in the museum’s opening show in its new home downtown in 2015, America Is Hard to See, which was visited by then-President Barack Obama. Mayerson has since created a new painting, based on an official photograph of the world leader standing solemnly in front of the original, “with all the feelings and emotions that I felt about this crisis, and how it has gone on to effect America and world civilisation, the wars and the missteps, and the reorganisation of our politics and ideology”.

The multidisciplinary artist Paul Chan says the 9/11 terrorist attacks have deeply inflected works like The 7 Lights (2005-07), a series of animations created with obsolete computer software that explore themes such as faith, technology and politics. In the earliest work in the series, 1st Light, currently on view at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), the shadows of abandoned vehicles, cell phones and other debris rise while apparitions of bodies fall from the sky; in the title, “Light” is struck out, MoMA notes, “suggesting its impending absence”.

Chan says he was trying to find a form that “expressed more than mere tragedy” and invoked “the social, political and spiritual conditions that underwrote what happened” on 9/11.

Over time, he adds, the attacks have had an enduring impact on his philo-sophy. “I think it is affecting in the same way anything momentous—like the birth of a child, or the death of a loved one” tends to be, he says. “It reminds me how little time there is left, for any of us, all that has been lost, how close it all is from disappearing, and what it takes to go on.”

Source link : https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/artists-remember-11-september