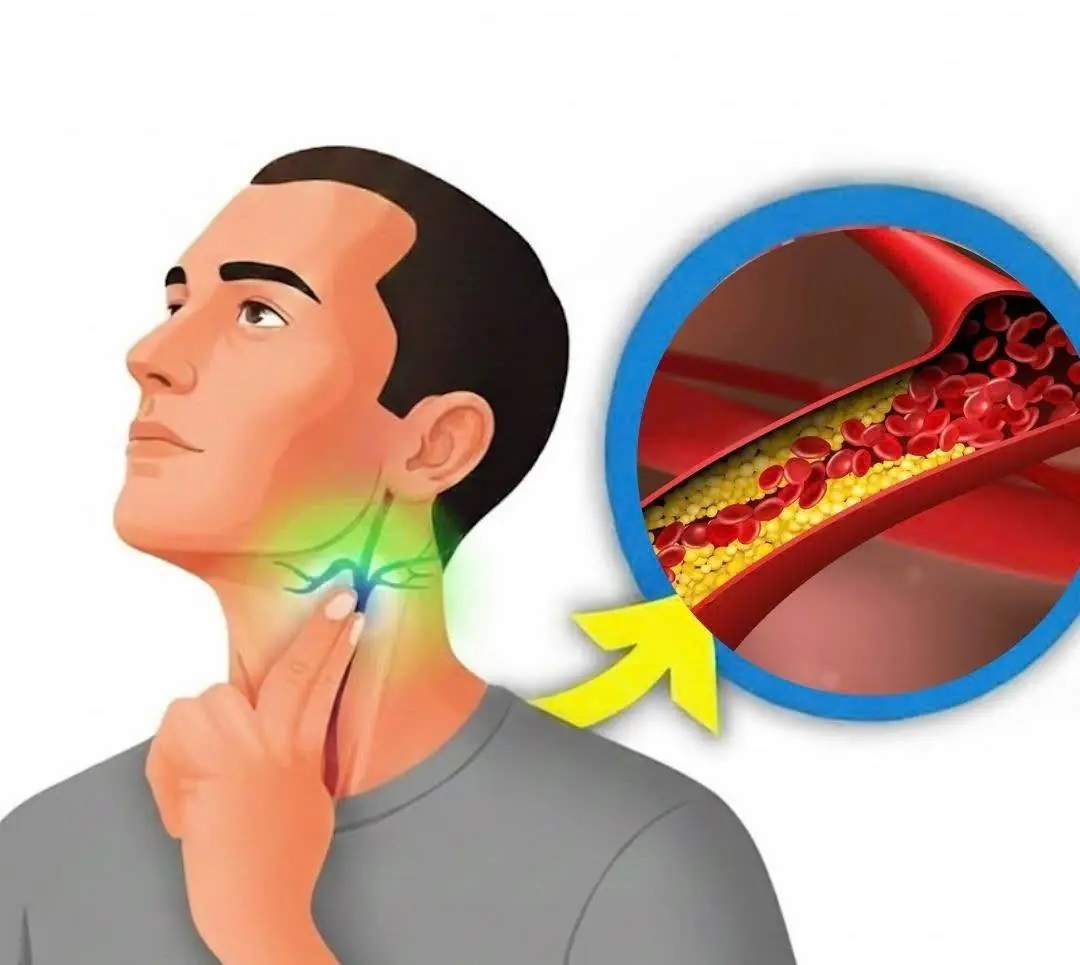

7 Early Signs Your He.art May Be in Dan.ger — Don’t Ignore These Warning Signals

Many People Miss These Early Heart Warning Signs

Many People Miss These Early Heart Warning Signs

The Amazing Health Benefits of Coconut You Should Know

Doctors reveal the surprising truth about eating red cabbage… See more

What Happens to Your Body When You Sleep with a Fan Running?

Why Do Your Legs Often Feel Numb? Common Causes and Conditions

What Happens When You Put Peppercorns Under Your Bed?

Stop the Pain: 3 Powerful Home Remedies for Canker Sores

Some common foods may contain parasites if poorly handled or cooked.

Kidney Red Flags: Warning Signs Your Body Is Trying to Tell You

One Natural Ingredient That Can Transform Your Skin

Thick ice in your fridge can be removed quickly with this trick.

Peanuts offer nutrients but may affect health in certain cases.

Some morning eating habits may affect long-term stomach health.

4 morning foods to eat on an empty stomach for a healthier gut and better digestion

Drinking Lemon Peel Water Daily: 5 Powerful Health Benefits You Should Know

Effective Ways to Reduce Water Retention Naturally

If your legs cramp at night, you need to know this immediately

No more night cramps — here’s how to avoid them

6 Best Remedies That May Help Keep Your Arteries Healthy and Improve Circulation