Hordes of visitors descend on the cemetery in the village of Auvers-sur-Oise, north of Paris, to see the two simple graves of Vincent and Theo van Gogh. For most, it is an emotional experience to gaze at the simple headstones of the two brothers, buried side by side and covered by a single blanket of ivy—one of the artist’s favourite plants.

But few of the “pilgrims” on the Van Gogh trail realise that this is not where Vincent was originally buried. In my new book Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers and the Artist’s Rise to Fame I reveal the astonishing story of how Vincent’s remains needed to be moved in 1905, when the original 15-year lease on his first grave in the cemetery expired.

The exhumation and reburial was arranged by Paul Gachet, the doctor who treated Vincent after he shot himself on 27 July 1890, dying two days later. Theo’s widow Jo Bonger came to Auvers in 1905 to witness the exhumation.

It was an extremely gruelling experience for Jo. Along with Dr Gachet and his son, also known as Paul, she watched as the gravedigger reached Vincent’s rotted coffin. Gachet Jr later described how a thuja tree (from the cypress family), planted soon after the original interment, “spread its roots” around his torso, “penetrating the cavities between the ribs”. By chance, this was just where the bullet had entered Vincent’s chest. The gravedigger had to disentangle the roots from around the rib cage.

The cranium was then exposed, giving Dr Gachet the chance to observe “the huge skull, the cheekbones and the arch of the eyebrows”. Gachet Jr later commented that “unknowingly, we reenacted the scene of the gravediggers from Hamlet”. The doctor handed the skull to his son, who gently placed it at the end of the new coffin. For Jo’s sake, the exhumation needed to be completed swiftly, although Dr Gachet had wanted to “study the ensemble, and particularly the skull”.

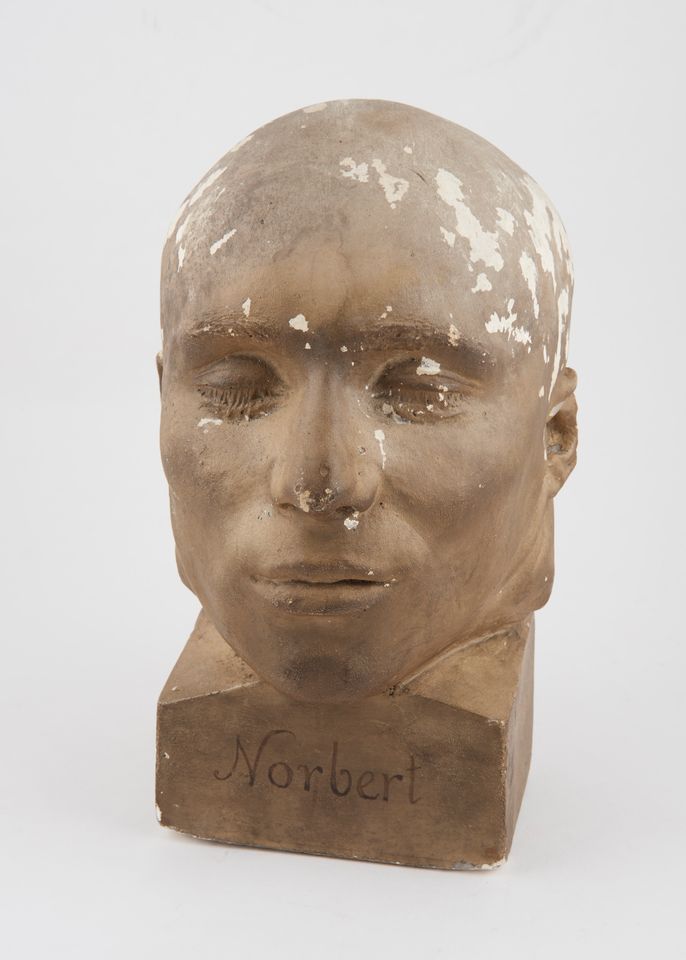

Dr Gachet’s interest in Van Gogh’s skull was because of his belief in phrenology, the now discredited idea that the shape of a person’s skull reveals something of their personality. This led the doctor to assemble a collection of plaster casts of heads of executed criminals. These bizarre objects, made immediately after guillotining when the neck swells up, have an exceptionally gruesome appearance. Several of Dr Gachet’s casts are now at the Science Museum in London. One of Joseph Norbert (guillotined in 1843) has phrenological markings, probably added by the doctor.

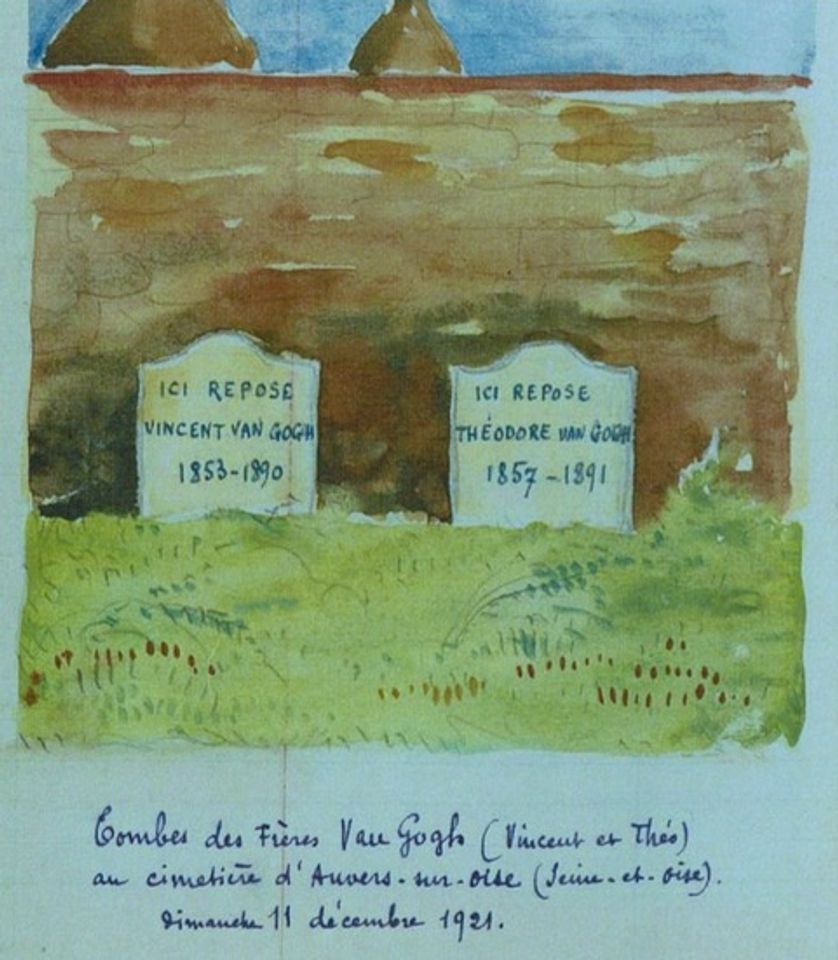

Until recently no images were known of Van Gogh’s first grave, but a watercolour has recently surfaced. It is published here for the first time in an English-language publication (it was tracked down by the German journalist and Van Gogh specialist Stefan Koldehoff, who reproduced it in Art: Das Kunstmagzin).

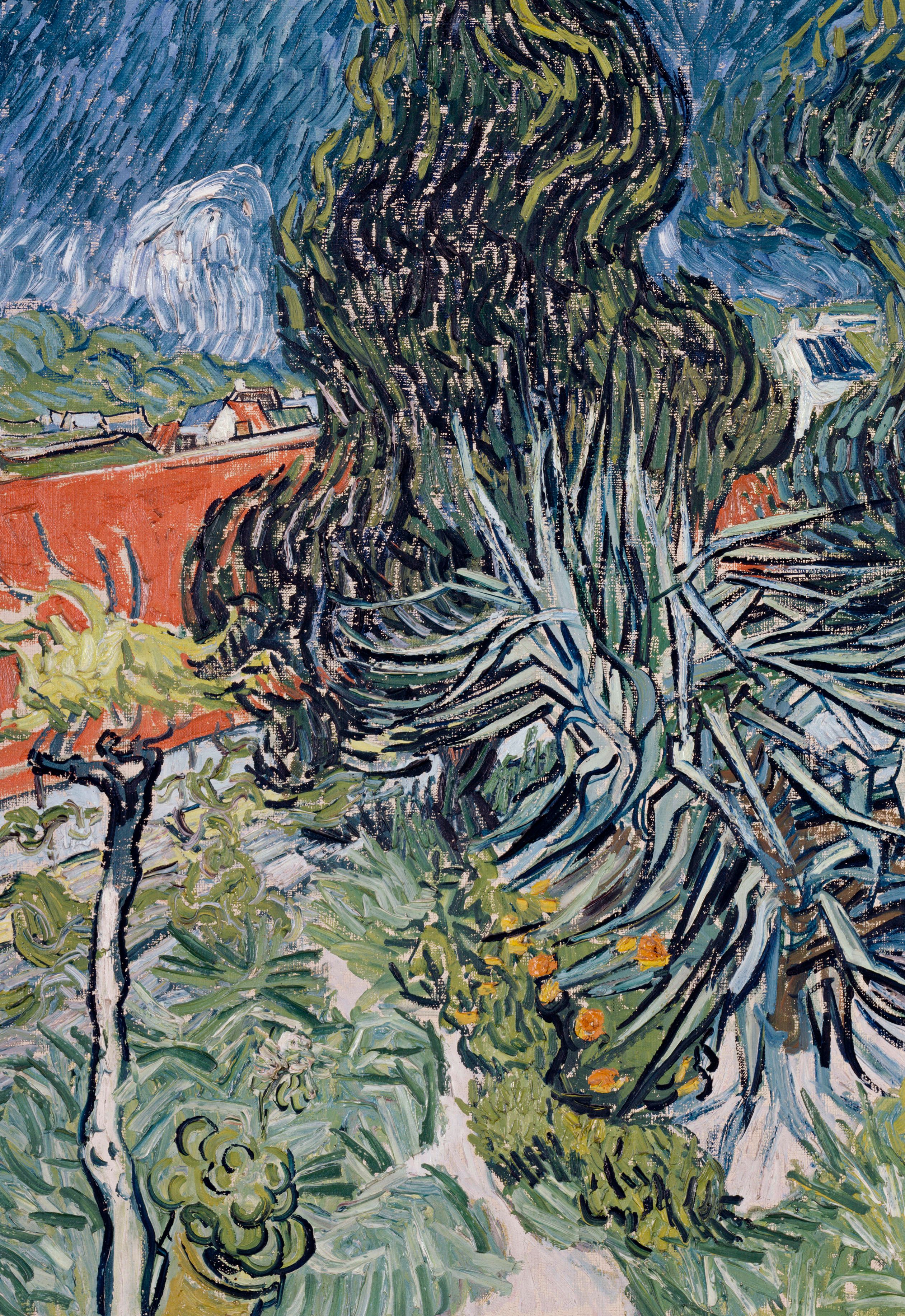

Painted by Dr Gachet’s art student Blanche Derousse, the sepia-coloured sketch reveals that the grave was dominated by shrubbery. A yucca almost hides the gravestone and a pair of thujas tower above at the side. Although it is unusual for such substantial plants to be grown over a grave, the idea was to surround the artist with his beloved nature. Cuttings or small plants of the yucca and thujas were apparently transplanted from Dr Gachet’s own flower beds, and large examples of them feature prominently in Van Gogh’s painting In the Garden of Dr Paul Gachet.

Despite extensive investigations, it has proved difficult to pinpoint the precise spot where Vincent was originally buried in 1890. Andreas Obst, a German Van Gogh researcher, is the only person to have conducted an in-depth investigation (his detailed report on Records and Deliberations about Vincent van Gogh’s First Grave was privately published). He believes that the original grave was in the north-west corner of the cemetery, a few plots from the northern end and roughly south of a gateway (in what was then, but not now, the fifth row).

Once it was realised that Vincent’s remains needed to be moved, Jo decided that it would be appropriate to move her husband’s remains from Utrecht, where he had been buried after his death in an asylum there. The move of Theo’s bones was delayed for several reasons, and was only accomplished in 1914, just months before the outbreak of the First World War. A headstone was carved for Theo (inscribed Theodore), matching that of his brother.

Both read “Ici repose” (Here rests). The words are particularly poignant, considering Vincent’s unsuccessful quest for peace of mind during his lifetime.

Although unpublished until now, the earliest image we have of the pair of graves is a simple watercolour sketch by Gustave Coquiot, who wrote the first detailed biography of the artist. His painting is in a notebook which covers his visit to Auvers in 1921.

And what about the bullet that brought Vincent’s life to an abrupt end? It may well have been removed before the funeral, but if it had remained in his chest, then it would very likely have become dislodged when the thuja root was untangled from the ribs in 1905. Gachet Jr does not mention the bullet in his explicit description of the exhumation. This suggests, although it does not prove, that the projectile may possibly have been extracted before the 1890 burial.

As for the thuja which was disentangled from Vincent’s chest, tradition has it that the bush was brought back to the Gachet residence, where it had originally started life. Replanted near the front door, it continues to thrive and has now become a mature tree.

Other Van Gogh news:

A painting owned by the New York collector Stuart Pivar has been dismissed by the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam as a fake. Pivar, who is convinced of its authority, filed a complaint with the New York County Supreme Court on 7 September after the museum declined to authenticate the doubtful work.

Martin Bailey is a leading Van Gogh specialist and investigative reporter for The Art Newspaper. Bailey has curated Van Gogh exhibitions at the Barbican Art Gallery and Compton Verney/National Gallery of Scotland. He was a co-curator of Tate Britain’s The EY Exhibition: Van Gogh and Britain (27 March-11 August 2019). He has written a number of bestselling books, including The Sunflowers Are Mine: The Story of Van Gogh’s Masterpiece (Frances Lincoln 2013, available in the UK and US), Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence (Frances Lincoln 2016, available in the UK and US) and Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum (White Lion Publishing 2018, available in the UK and US). Bailey’s Living with Vincent van Gogh: The Homes & Landscapes that Shaped the Artist (White Lion Publishing 2019, available in the UK and US) provides an overview of the artist’s life. His latest publication is the reissued book The Illustrated Provence Letters of Van Gogh (Batsford 2021, available in the UK and US).

• To contact Martin Bailey, please email: [email protected] Please kindly refer queries about authentication of possible Van Goghs to the Van Gogh Museum.

Read more from Martin’s Adventures with Van Gogh blog here.

Source link : https://www.theartnewspaper.com/blog/where-was-van-gogh-originally-buried-we-still-don-t-know