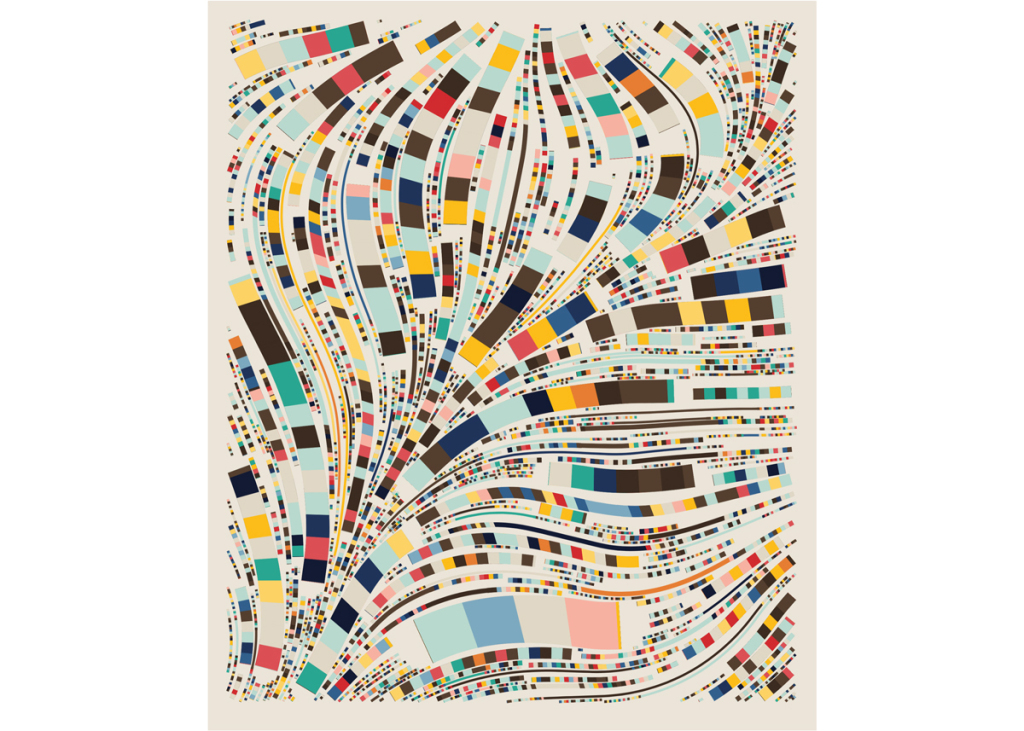

Tyler Hobbs, Fidenza #313 (Tulip), 2021 Art Blocks

Tyler Hobbs, Fidenza #313 (Tulip), 2021 Art Blocks

“The most popular series of NFT collectibles are algorithmically generated,” Dean Kissick, the New York editor of Spike Art Magazine, wrote in a column back in March, when the NFT craze was just exploding. He was describing the algorithm’s claustrophobic effect on culture, and he isn’t alone in his prognostic. There are many critics who claim that algorithms do two things: produce bad art and cheapen culture as a whole.

The problem, Kissick wrote, is “we want too much content, too fast, and it just leads to this endless algorithmic churning, this paint-by-numbers effect. You see it in art. In Netflix documentaries. Spotify playlists. Op-ed pages. The news. The latest manufactured outrage. Well-reviewed first-person novels about nothing. All so dreadfully banal and repetitive.”

That was last March, long before algorithmic art would come to dominate the NFT space and breach the walls of the fine art world via the auction houses. This past season—which crypto enthusiasts have taken to calling the “JPEG summer”—saw the rise of massively successful profile-pic NFT projects (PFP NFTs) like Bored Ape Yacht Club and Pudgy Penguins. These series capitalize upon the success of CryptoPunks, a series of pixelized portraits of punks, which continue to dominate as the NFT scene. Each of these projects shares a process which depends on algorithms. A bucket of virtual assets—different design features, accessories, and special traits—is created and then mashed together using a procedural generation algorithm that creates thousands of unique combinations.

This type of art-making, the PFP project creator Franky Aguilar recently pointed out, “is a very easy way to generate 10,000 unique images.” Evidently, the challenges that come with making a successful PFP project hardly lie with the artistic process. Yet they’ve come to define the most sought-after assets on the NFT market. Sotheby’s just realized $24.4 million for a bundle of 101 Bored Apes from the Bored Ape Yacht Club collection. Christie’s will be offering their own PFP sale next week. From a critic’s perspective, this is exactly the problem—the line between manufactured collectibles and unique art works has almost completely collapsed.

Not all algorithmic art has to be this simplistic. A new generative art platform, Art Blocks, has set out to prove that art made with algorithms can be complex and genuinely aesthetically compelling. On Art Blocks, artists upload their algorithm and cap the number of iterations it can produce. Buyers select an algorithm with a style they like and then mint pieces, each of which is unique but randomly generated. It functions a bit like a “get-what-you-get” gumball machine, except some treat what comes out like a stock option.

Art Blocks isn’t as worried about the long-term value of NFTs as they are about raising the standards of algorithmic art. “Until today, a [generative] artist would create an algorithm, press the spacebar 100 times, pick five of the best ones and print them in high quality,” Erick Calderon, the CEO and founder of Art Blocks, said, explaining how generative artists typically make their work. Then they would “frame them, and put them in a gallery. Maybe.”

But Art Blocks has completely changed the status quo for generative art. “Because Art Blocks forces the artist to accept every single output of the algorithm as their signed piece,” Calderon said, “the artist has to go back and tweak the algorithm until it’s perfect. They can’t just cherry pick the good outputs. That elevates the level of algorithmic execution because the artist is creating something that they know they’re proud of before they even know what’s going to come out on the other side.”

Chromie Squiggle, the first series to go up on Art Blocks. Art Blocks

Chromie Squiggle, the first series to go up on Art Blocks. Art Blocks

Though generative art began in the 1960s, it’s still an emerging art form. More importantly, the top collectors of generative art, people in the crypto and NFT communities, are themselves only now beginning to approach questions of value, subjective taste, and aesthetics. For the layman, and even those who are highly technologically proficient, there’s a learning curve in understanding what makes for good generative art, like a complex code that achieves both high variety and consistent quality.

This attention to quality is paying off. In August, Art Blocks saw nearly $600 million (184m Eth) in sales across 51,000 transactions involving more than 12,000 buyers. On August 23, Art Blocks had a peak selling day where $69 million in transactions occurred. Christie’s will be offering NFTs produced through Art Blocks in an October postwar and contemporary art auction. According to a report by Dapp Radar, a data analytics company focused in decentralized apps, the wealthiest collectors in the NFT space (commonly referred to as “whales”) own Art Blocks pieces and are, on the whole, refusing to sell. “It is clear that some collections are now perceived as safe assets for storing and gaining value,” the report says, “as is the case of Art Blocks and CryptoPunks where their whales did not reduce their current holdings, but they increased them (in the case of Art Blocks).”

Generative artists, for their part, believe that their medium is here to stay. Artist Tyler Hobbs, who has produced work using Art Blocks, said in an email, “The bulk of our lives [is] moving into digital environments, which are of course constructed with algorithms. Should artists strain to avoid these algorithms? No, we’re better off claiming them for ourselves.” In response to Kissick’s critique, Hobbs added, “I won’t claim that most algorithmic artwork is good, or that there aren’t a large number of people in it for the money, as always. But, if you actually understand the art form I think you’ll see that at the core there’s something special taking place.”

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/algorithm-generated-nfts-art-blocks-1234603548