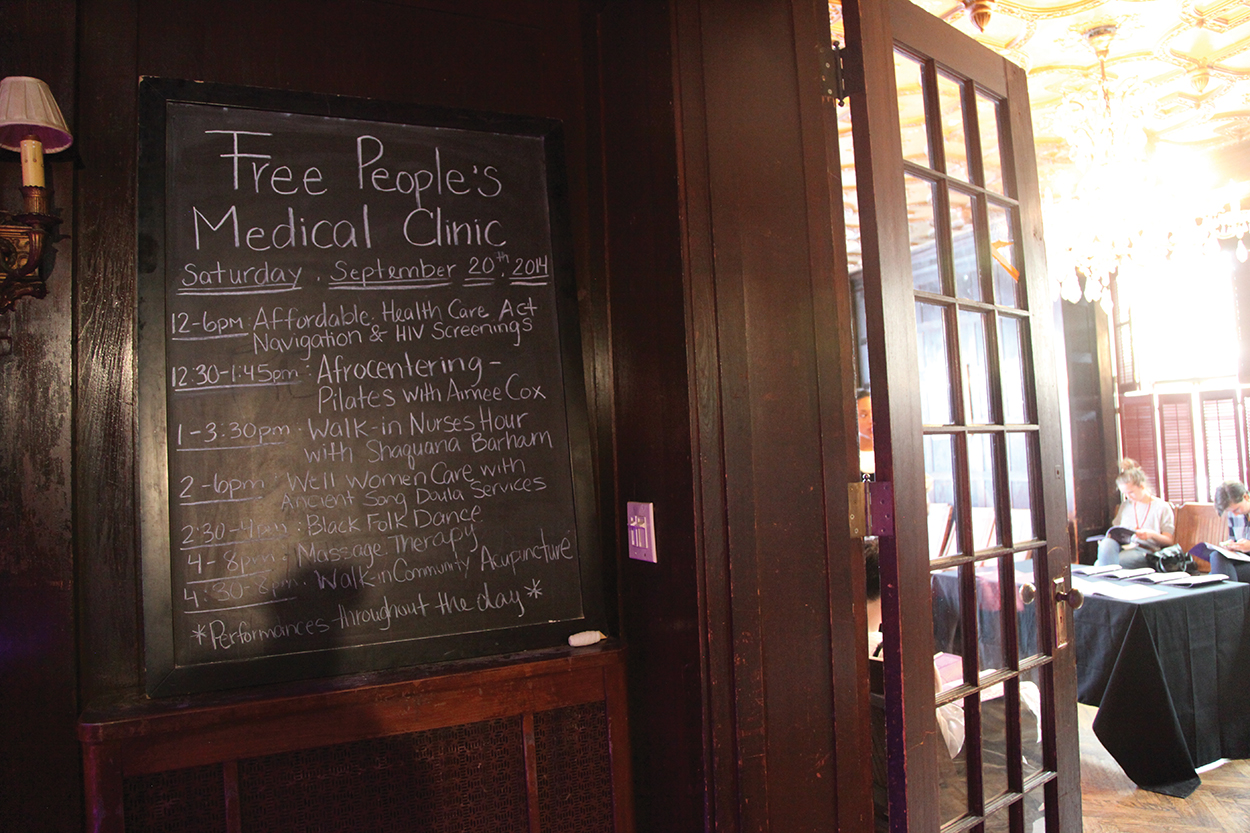

View of Simone Leigh’s Free People’s Medical Clinic, 2014, at Weeksville Heritage Center, Brooklyn. Photo Shulamit Seidler-Feller/Courtesy Creative Time

View of Simone Leigh’s Free People’s Medical Clinic, 2014, at Weeksville Heritage Center, Brooklyn. Photo Shulamit Seidler-Feller/Courtesy Creative Time

“Mystery,” “riddle,” and “secret” are words found in much of the writing about Simone Leigh. Not only do they aptly characterize her majestic, figurative sculptures with eyeless faces, they especially suit Free People’s Medical Clinic (2014) and its progeny, The Waiting Room (2016). Both presented in New York, these were experience-based social practice works, in which various healing justice practitioners—nurses, herbalists, yoga instructors, and others—provided free services, often directed specifically toward Black women. Even if photos could do them justice, few can be found online. Adding to the enigma, my requests for images from Stuyvesant Mansion, once the home of Josephine English, the first Black gynecologist in the state of New York, and the site where Free People’s Medical Clinic was originally staged, went unanswered, as did requests for comment from several people and organizations involved in the show’s planning, execution, and documentation.

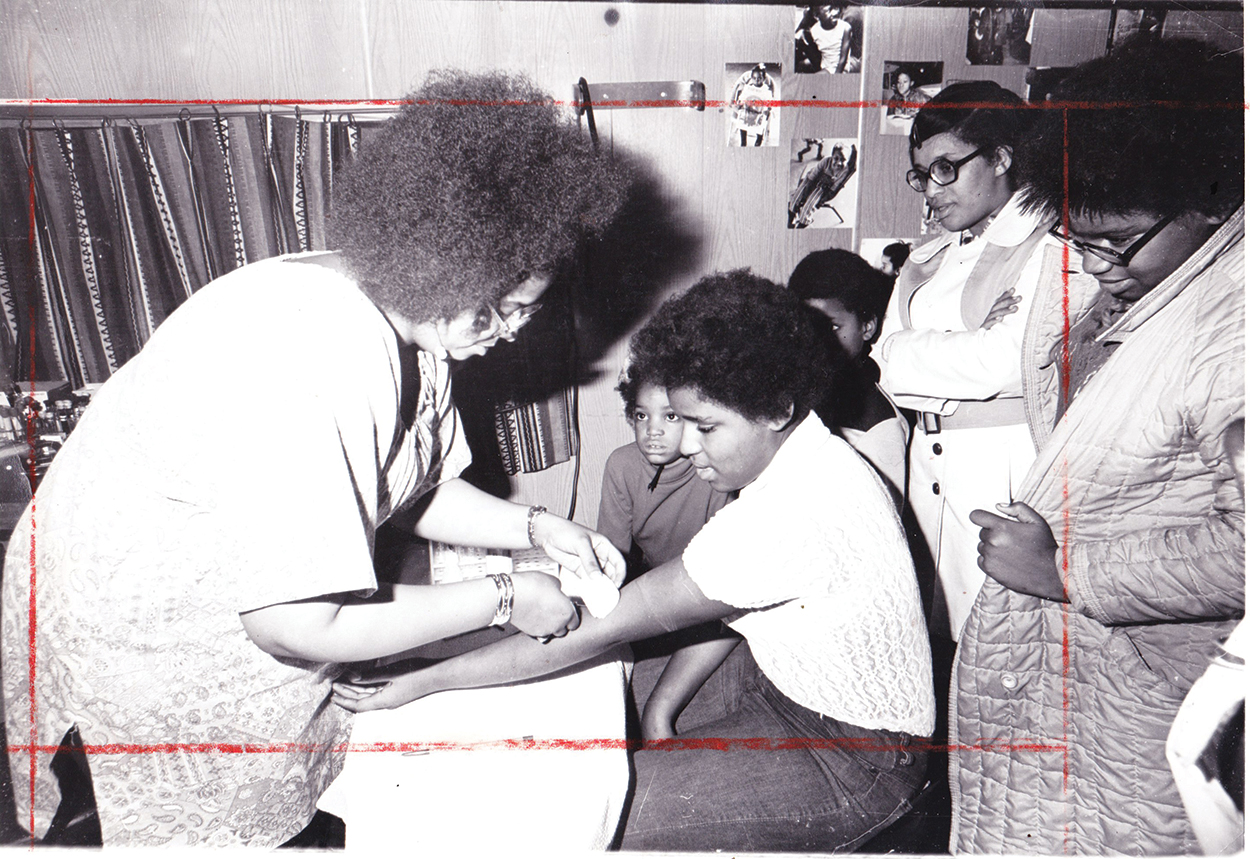

Eventually, after many attempts to contact anyone qualified to speak about either exhibition, it became clear that this privacy is essential to the preservation of the work. The silence around Leigh’s projects is a deliberate choice. Privacy and dignity are key concerns when it comes to the health and safety of Black people; they can be a matter of life or death. To keep vital healing modalities alive, be they traditions of medical herbalism or corps of Black nurses organizing care for elderly and sick people, they must be kept secret, or they risk being destroyed. That is, if the two precedents to which Leigh repeatedly refers are any indication. She frequently invokes the United Order of Tents, a secret society for Black women medical professionals that was founded in Virginia in 1867 and continues today. The Order maintains both its roster and healing practices for members only. A volunteer-run Black Panther initiative is the source of Leigh’s 2014 title, Free People’s Medical Clinic. From 1968–75, the Party’s clinics were frequent targets of police raids and building evictions.

Black Panther Party nurse administering blood test in NewYork, 1971. Courtesy It’s About Time Archive

Black Panther Party nurse administering blood test in NewYork, 1971. Courtesy It’s About Time Archive

The bulk of available photo documentation focuses on the healing service providers who participated in Free People’s Medical Clinic, a Creative Time commission that operated for one month at the Brooklyn mansion. The providers included yoga and Pilates instructors, herbalists, nurses, and individuals trained to help participants navigate the Affordable Care Act. They were dressed in uniforms that resemble those worn by members of the United Order of Tents. In Creative Time’s introduction to Free People’s Medical Clinic, such providers are cast as the impetus for the work, and the clinic is called “a temporary space that explores the beauty, dignity and power of black nurses and doctors, whose work is often hidden from view.”

BLACK HEALTH SEEMS DOOMED to be pulled between poles of spectacle and invisibility. The Waiting Room, which took a format similar to that of the 2014 work, was installed at the New Museum and at times included events open exclusively to Black women. The work’s title refers to the death of Esmin Elizabeth Green, a Jamaican woman who died in 2008 after being neglected for a full day in the waiting room of Kings County Hospital Center in Brooklyn, where she sought psychiatric care. Her body lay for more than an hour on the floor where she collapsed, publicly visible and captured on the hospital’s camera system; a staffer, perhaps to confirm she was dead, kicked her body. The video still exists online.

View of “Simone Leigh: The Waiting Room / Herbs for Energy and Pleasure with Karen Rose,” 2016, at the New Museum, New York. ©Simone Leigh/Courtesy the artist and New Museum

View of “Simone Leigh: The Waiting Room / Herbs for Energy and Pleasure with Karen Rose,” 2016, at the New Museum, New York. ©Simone Leigh/Courtesy the artist and New Museum

But the work is not a response to Green’s death alone, as her story is no anomaly. Barbara Dawson died in 2015, also of a pulmonary embolism for which she was not treated. Instead of being neglected, she was arrested while seeking care that she hoped would save her life. When the doctors could not find the clot of which she complained, she was taken for a liar. When she insisted that she knew her body best, that she had a right to live, pleading “please don’t let me die,” care was not rendered; instead, the police were notified. “Either walk out of the hospital peacefully or I can take you out,” a cop demanded, relenting only when she became unresponsive.

This is what can happen when Black women and gender minorities seek health care in a field whose history is deeply entwined with oppression. Consider the origins of American gynecology itself, which relied on enslaved Black women as public test subjects in operating theaters and on plantations throughout the United States. Dr. J. Marion Sims, considered “the father of modern gynecology,” received plaudits and statues for his deeds. So it’s no small choice to hold Free People’s Medical Clinic in the former home of Josephine English, who delivered the six children of El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz (once known as Malcolm X) and Betty Shabazz.

View of Simone Leigh’s Free People’s Medical Clinic, 2014, at Weeksville Heritage Center, Brooklyn. Photo Shulamit Seidler-Feller/Courtesy Creative Time

View of Simone Leigh’s Free People’s Medical Clinic, 2014, at Weeksville Heritage Center, Brooklyn. Photo Shulamit Seidler-Feller/Courtesy Creative Time

These are also precisely the conditions that inspired the Black Panther Party to create its Peoples’ Free Medical Clinics. There’s an astonishing symmetry between Leigh’s two projects and their less artistically focused antecedents. The HIV screenings held within the installations rhyme with the Party’s sickle cell anemia testing. Like the Party’s clinics, Free People’s Medical Clinic and The Waiting Room were staffed by volunteers. For the Black Panther Party, these volunteer professionals included physicians, pharmacists, lab technicians, medical students, and members of the National Black Nurses Association. Leigh hosted more esoteric wellness professionals alongside these traditional medical providers, including Karen Rose, a celebrated herbalist and owner of Sacred Vibes Apothecary in Prospect Park.

Leigh’s art exhibition focused on healing justice was temporary; it served to encourage work in the world rather than solve a systemic problem. While the Order remains in secrecy and the Panthers’ free clinics were destroyed, Leigh was able to create a model for healing justice in the space of the museum, receiving deserved praise instead of attacks.

IT’S TOO EASY, though, to think of the Panthers’ approach to healing justice as inherently radical and Leigh’s as only working within the framework of the capitalist art world. To do this neglects the historical necessity of sneaking pleasure and breathing room under the nose of an oppressor. As a former organizer, I’ve seen resilience-based actions, such as community gardening and wellness, demeaned to lift up protests and other direct approaches to insurrection. But where do we fill our cup, where do we go to imagine what’s possible when we are done fighting, and what’s on the other side of the movement if it succeeds? These are questions that art can help answer, because it seeks possibilities in the face of current conditions.

Simone Leigh, Brick House, 2019, bronze,196 by 114 inches. Photo Timothy Schenck/©Simone Leigh/Courtesy the artist and High Line

Simone Leigh, Brick House, 2019, bronze,196 by 114 inches. Photo Timothy Schenck/©Simone Leigh/Courtesy the artist and High Line

Leigh’s projects presented an alternative to the Western biomedical understanding of health—a realm where Black women are believed when they talk about their bodies and needs, where their decisions are the final word about which healing practices suit them, and where they are no longer punished for failing to comply. Care sessions were interspersed with lectures, public workshops, and the procession of at least 100 Black women artists. Both exhibitions were positioned as a “DIY model for spiritual and physical wellbeing,” as curator and writer Jared Quinton phrased it on Artsy. Unless these alternative approaches to spiritual, physical, and emotional wellness exist alongside Western biomedicine, Black people cannot thrive.

Free People’s Medical Clinic and The Waiting Room both reflect lineages of healing resistance, and reintroduce those modalities to communities in need of that historical knowledge. This is essential, as we are often isolated from our ancestral forms of healing, including forms of herbalism traditional to West Africa, movement practices lost to the Middle Passage, and other forms of physical and emotional resilience-building that sustained us prior to and throughout enslavement. Drawing from older traditions of African and African diasporic modes of creation and healing, these works succeed in showing the through line between what has already been built and what is yet to be.

Free People’s Medical Clinic brought an end to Leigh’s clinic-based work. The artist was born in Chicago to Jamaican immigrants in 1967, studied feminist and postcolonial theory at Earlham College in Indiana, and taught herself ceramics. Following these installations, she pivoted to figurative sculptures. In April 2019, Leigh told Elizabeth Karp-Evans at Cultured magazine that she “‘will not create social practice works anymore, at least not any more public-facing works,’ as too much of it was ‘out of [her] control.’” Although Leigh didn’t go into specifics, there’s something to be said about how turning Black healing into an artwork could result in hollow voyeurism. By providing healing to communities in need but limiting who could view the documentation and, at times visit the installation/performance—Leigh managed to strike a delicate balance by making sure Black healing practices didn’t get overlooked or forgotten, while also refusing to allow them to be turned into spectacles.

LEIGH’S MONUMENTAL SCULPTURES are much more visible—one has been displayed on Manhattan’s High Line, and in 2022, a number of them will appear at the Venice Biennale, where Leigh will be the first Black woman to stage a solo exhibition in the US pavilion there. But they are also more enigmatic than the clinic-based projects. They suggest the maturation of her strategy of refusal and concealment. Many stand like watchful deities, and sometimes feature a melding of Black women’s forms with various objects. In an essay accompanying Leigh’s 2019 Guggenheim Museum exhibition in New York—she was also the first Black woman to receive the institution’s Hugo Boss award—writer Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts contemplates one of the prominent mysteries of the artist’s work: why the figures have no eyes. “Perhaps through their unseeing eyes we may comprehend the riddle of private and public and publics winding across Leigh’s multiple arenas of engagement,” she offers. “Perhaps it’s a riddle Leigh answers as easily as she sometimes offers an entry and elsewhere seals it up.” Whether invoking craft traditions or healing practices, Leigh has long been interested in honoring Black culture without allowing it to be subsumed by the white-dominated art world.

The sculptures not only center Black women, but engage them as the most relevant interlocutors for her art. “Black women are my primary audience,” the artist wrote in a viral 2019 Instagram caption addressing white art critics’ assertion that her sculptures in the Whitney Biennial were insufficiently radical. Sentinel IV (2020) is a sleek, towering female figure, breasts pointing out like small arms to either side, with a mesmerizing concave head. The figure draws its form from ceremonial wooden ladles of nineteenth- and twentieth-century Dan communities of Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire, where oversize figurative spoons were presented to women as tokens of gratitude. The work’s placement in the recent New Museum show “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America”—adjacent to Kerry James Marshall’s Souvenir IV (1998), which features a figure similar to Sentinel IV on display in a living room—is a testament to the timelessness of Leigh’s work.

Leigh’s collaborative practice is often intergenerational. Not only does she spotlight ancestral knowledge, she also incorporates many genres of Black women’s art. As part of The Waiting Room, she founded and coordinated Black Women Artists for Black Lives Matter, that previously mentioned procession of more than 100 artists, all of whom responded to a call from the Movement for Black Lives. The “women filled the institution from white wall to white wall with performances, workshops, videos, chants, a text collage, a digital altar,” Jillian Steinhauer reported for Hyperallergic. “The space swelled with an unapologetically empowering celebration of Black women[’s] . . . lives. It was unlike anything I’ve ever seen in a museum.”

THROUGHOUT THE PAST YEAR, there seemed to be no alternative to the medical industrial complex that experiments on us, incarcerates us when we seek care, and leaves us to die in emergency rooms. That the disposition of the US medical profession has changed so little in the intervening half-century since the Panther clinics confirms the necessity and inherent radicality of Free People’s Medical Clinic and The Waiting Room. Black people were two times more likely to die of Covid-19 than white people, and were far more likely to bear the most harrowing consequences of the infection despite not being the race most likely to contract it. The alternatives imagined by The Waiting Room and Free People’s Medical Clinic seemed as urgent as ever. So why terminate such a vision of possible futures?

Leigh never wanted the works to be “heroic,” she told William J. Simmons in Interview. She didn’t think that they could save anyone. “My project was to expose an arena of expertise, a gold mine of knowledge that we have ignored, or even that we don’t know exists,” she explained. “I did not intend to set up a mock NGO pretending to rescue Black people from some abject situation. I’m tiring of having to talk about that post-colonial fantasy. This insistence on focusing on this same savior narrative is so perverse.” The world-building of these two shows was not meant to last forever, but here we are, seven years on, returning to these models as proof of concept.

Inside the purple covers of Waiting Room Magazine, the companion text to the 2016 installation, there’s an archival advertisement that reads: THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY ANNOUNCES THE GRAND OPENING OF THE BOBBY SEALE PEOPLES’ FREE HEALTH CLINIC. SERVING THE PEOPLE BODY AND SOUL. The magazine, which was impeccably bound by Zimbabwean designer Nontsikelelo Mutiti, was filled with Black medical ephemera ranging from an article by writer A. Naomi Jackson to the memoirs of a nurse who served during the American Civil War. It’s not easy to find a copy now that the show is over, which could be said for almost any exhibition catalogue. Those who attended the exhibitions will be able to refer to the text; those who weren’t will likely never see what it holds. Here again, the privacy embedded even in Leigh’s public-facing work is deliberate and carefully negotiated.

Yet her demand for privacy is paradoxically emphatic—public, even, and her model contains a multitude of possibilities for Black artists prioritizing their own wellness. It rings in the message of artist Tricia Hersey’s project The Nap Ministry, which bears the slogan OUR REST IS RESISTANCE, and lives in Naomi Osaka’s refusal to participate in a press conference while her mental health suffered. This demand for privacy to create, heal, and truly live is a stance of protection—one that must be carved out and fiercely protected.

The energy perserved by this carving is among its rewards. In 2018, Black women activists pushed a Central Park statue of J. Marion Sims from its plinth. Meanwhile, Simone Leigh’s statues continue to rise around the world.

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/simone-leigh-healing-1234603507