Sitting atop a hill in the City of Westminster, Charing Cross station serves more than 30million passengers every year.

Since its first opened in 1864, the transport hub has provided the perfect connection point for visitors who are seeking to make the most of the myriad entertainment venues nearby.

But a new TV documentary tells how, because the station was built on the top of a steep slope down to the River Thames, it needed the support of the network of barrel vaults which – unbeknown to most passengers – lie 40 feet beneath it.

In tonight’s episode of The Architecture the Railways Built, which airs on UKTV channel Yesterday at 8pm tonight, historian Tim Dunn is seen touring the incredible spaces, which are not open to the public.

He is told how the vaults were rented out by neighbouring West End businesses to store stock and is then shown discarded wooden caskets which once stored wine. In a sign of the origins of one vintage, a box has ‘French, 1950’ scrawled on it in chalk.

The historian is also given exclusive access to the £300-a-night four-star hotel above the station which has catered to wealthy travellers and other Londoners since it opened in 1865.

Amazingly, the venue’s ballroom, which boasts Tuscan-inspired pillars and ornate octagonal-patterned ceilings, has not been changed since it was originally designed by esteemed architect Edward Middleton Barry.

A new TV documentary reveals the network of barrel vaults beneath Charing Cross station which prevent it from slipping into the River Thames. Pictured: The arched vaults which are revealed in tonight’s episode of The Architecture the Railways Built, It airs on UKTV channel Yesterday at 8pm tonight

Sitting atop a hill in the City of Westminster, Charing Cross station serves more than 30million passengers every year. Since its first opened in 1864, the transport hub has provided the perfect connection point for visitors who are seeking to make the most of the myriad entertainment venues nearby

Mr Dunn tells in tonight’s show how Charing Cross stands on the site of the former Hungerford Market, which had existed since the 18th century.

Private firm the South Eastern Railway bought the market site after it was badly damaged in a fire in 1854. They then demolished it to make way for Charing Cross station.

At the same time, a suspension bridge built by civil engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel which had led to the market from Lambeth on the south bank of the Thames was replaced with the new Hungerford Railway Bridge.

Urban historian Mike Althorp explains in tonight’s programme: ‘The station stands on the site of the former Hungerford Market; which was created as this spectacular Italianate series of arcades and trading floors which followed the line of the land down to the river.

‘So when the station arrived it also had to deal with the topography. We are on the top of a very steep slope down to the Thames.

‘They had to build up the structure, so underneath the hotel there is a whole sequence of barrel vaults and brick viaducts holding up this whole station.

Historian Tim Dunn is seen touring the incredible spaces, which are not open to the public. He is told how the vaults were rented out by neighbouring West End businesses to store stock and is then shown discarded wooden caskets which once held bottles of wine

In a sign of the origins of one vintage, a box has ‘French, 1950’ scrawled on it in chalk. The caskets are stored around 40 feet beneath the busy station

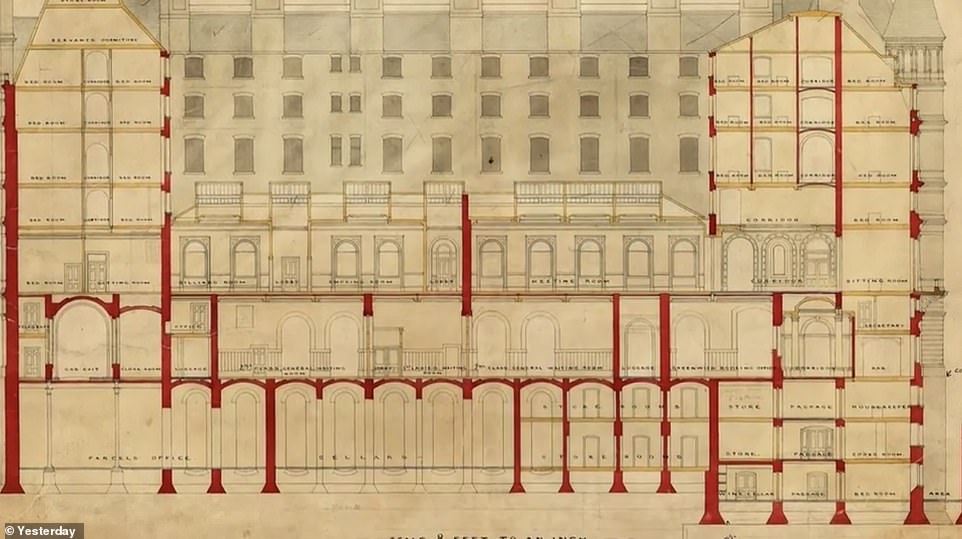

A fascinating diagram revealed in the programme shows how Charing Cross is built above a network of support structures

Mr Dunn tells in tonight’s show how Charing Cross stands on the site of the former Hungerford Market, which had existed since the 18th century

Urban historian Mike Althorp explains that because of Charing Cross’s position on top of a ‘very steep slope’ which leads down to the Thames, a ‘whole sequence of barrel vaults and brick viaducts’ hold up the station. Above: Some of the rooms beneath the station

Numbered concrete partitions give a hint as to how the space would have once been packed with caskets of wine. Now, only some of the dusty caskets remain

After being taken down beneath the station to view the brick vaults, Mr Dunn is told by his fellow historian how the structures are ‘making everything possible’ above ground

‘The engineering of the station and the bridges and most of all of the earthworks and everything that lies underneath this, the substructure, is by engineer John Hawkshaw,’ he added.

The original station building boasted a soaring arch supported by two tall retaining walls. However, in 1905, a 70-foot length of the roof collapsed and killed five people.

The accident led to the replacement of the original roof with a ridge and furrow design, which Mr Althorp says is ‘not nearly as spectacular’ as its predecessor.

After being taken down beneath the station to view the brick vaults, Mr Dunn is told by his fellow historian how the structures are ‘making everything possible’ above ground.

‘Primarily this was supporting structures but of course it being the South Eastern Railway Company, a commercial endeavour, this was space and it could be made profitable,’ he said.

‘So these were used as commercial stores for many neighbouring businesses in the West End. I believe at one point these were wine cellars as well.

‘They are empty today but these would have been packed out.’

Some of the arches which are publicly accessible are those which host shops and entertainment venues including the famous nightclub Heaven.

Mr Dunn is then taken upstairs to what is now the Clermont Hotel. Designed by Middleton Barry in a French Renaissance style, when it opened in May 1865 it was named the Charing Cross Hotel

The £300-a-night four-star venue has catered to wealthy travellers and other Londoners since it opened in 1865

Amazingly, the venue’s ballroom, which boasts Tuscan-inspired pillars and ornate octagonal-patterned ceilings, has not been changed since it was originally designed by esteemed architect Edward Middleton Barry

Above: The Tuscan-inspired marble pillars rise up to a bright white ceiling which is decorated with octagonal patterns

The hotel’s manager, Pedro da Silva, told Mr Dunn that Middleton Barry wanted to offer ‘something to the city that it had never seen before’

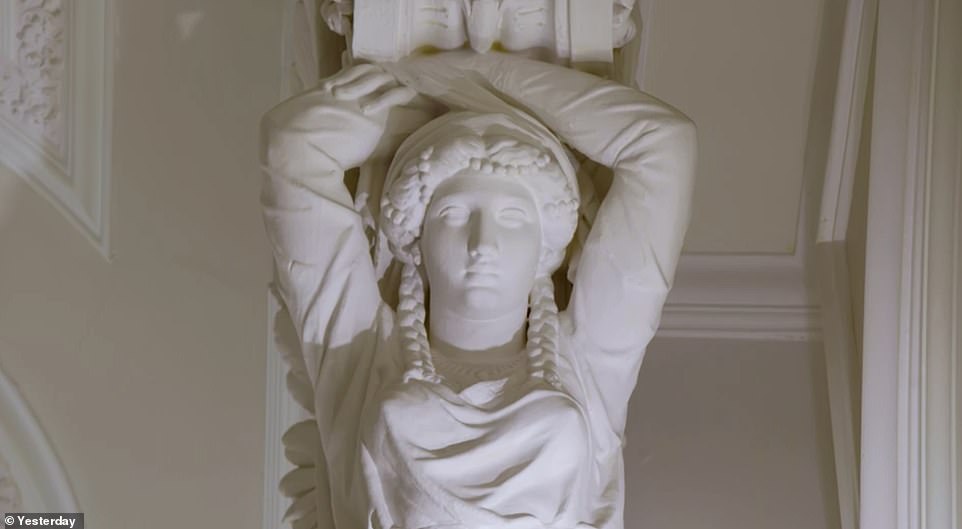

Also among the decorations in the exclusive hotel are a series of carved female figures such as the one above

The intricate ceiling design wows historian Mr Dunn. Mr da Silva adds: ‘Bearing in mind this is still the 1860s, it is mind-blowing the level of detail, the imagination and creativity they had’

The original hotel boasted 250 bedrooms spread across seven floors with views along Villiers Street and of the front of the Strand. Above: An early illustration of the establishment

Mr Dunn is then shown the wine cellars, which lie just feet away from the escalator leading from the Underground to Charing Cross’s booking hall.

Numbered concrete partitions give a hint as to how the space would have once been packed with caskets of wine. Now, only some of the dusty caskets remain.

Mr Dunn is then taken upstairs to what is now the Clermont Hotel. Designed by Middleton Barry in a French Renaissance style, when it opened in May 1865 it was named the Charing Cross Hotel.

It boasted 250 bedrooms spread across seven floors with views along Villiers Street and of the front of the Strand.

A series of iron and glass verandas built as part of the original design continue to overlook the station concourse.

The hotel’s manager, Pedro da Silva, told Mr Dunn that Middleton Barry wanted to offer ‘something to the city that it had never seen before’.

After being taken into the enormous ballroom, which remains as it looked in the 19th century, Mr Dunn is wowed by the stunning ceiling decorations and intricate wallpaper.

Mr da Silva adds: ‘Bearing in mind this is still the 1860s, it is mind-blowing the level of detail, the imagination and creativity they had.’

Source link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-10032647/The-secret-wine-cellar-keeping-Charing-Cross-station-SINKING.html