Usually when you hear names like Bacon, Rothko, Krasner, Pollock, Frankenthaler, Kline, de Kooning, Guston, and Giacometti all listed together, they are headlining a 20th- century evening sale at Christie’s or Sotheby’s. But major works by these artists are now heading in a different direction—to the Seattle Art Museum (SAM) in a donation that Mimi Gates, its former director, describes as “a game-changer in the status of the museum” that “lifts its collection to an entirely new level.”

The 19 works given to the museum come from the Friday Foundation, run by the heirs of the late Seattle arts patrons Jane Lang Davis and Richard E. Lang. The couple were very “gracious and serious” collectors, says Laura Paulson, the head of the Gagosian Art Advisory, who has been working with their foundation. “They were not buying trophies but lived with all of their art and loved planning trips to New York to see dealers who they trusted.” She describes their 10ft-tall stainless steel David Smith Cubi XXV, (1965), one of two sculptures in the donation, as particularly valuable, since only two of the artist’s 28 works from that series now remain in private hands.

Paulson declined to give an estimate for the total gift’s value, but Eli Broad bought the last Cubi sold at auction, 15 years ago, for $23.8m. The donation also features a four-foot-tall bronze Giacometti sculpture, Femme de Venise II (1956). The rest of the gift, save two works on paper by Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, are paintings in oil or acrylic.

Lisa Dennison, executive vice president and chairman of Sotheby’s Americas in New York meanwhile estimates the overall value of the gift at $400m, when added to a more modest donation of six works that the foundation is making to the Yale University Art Gallery.

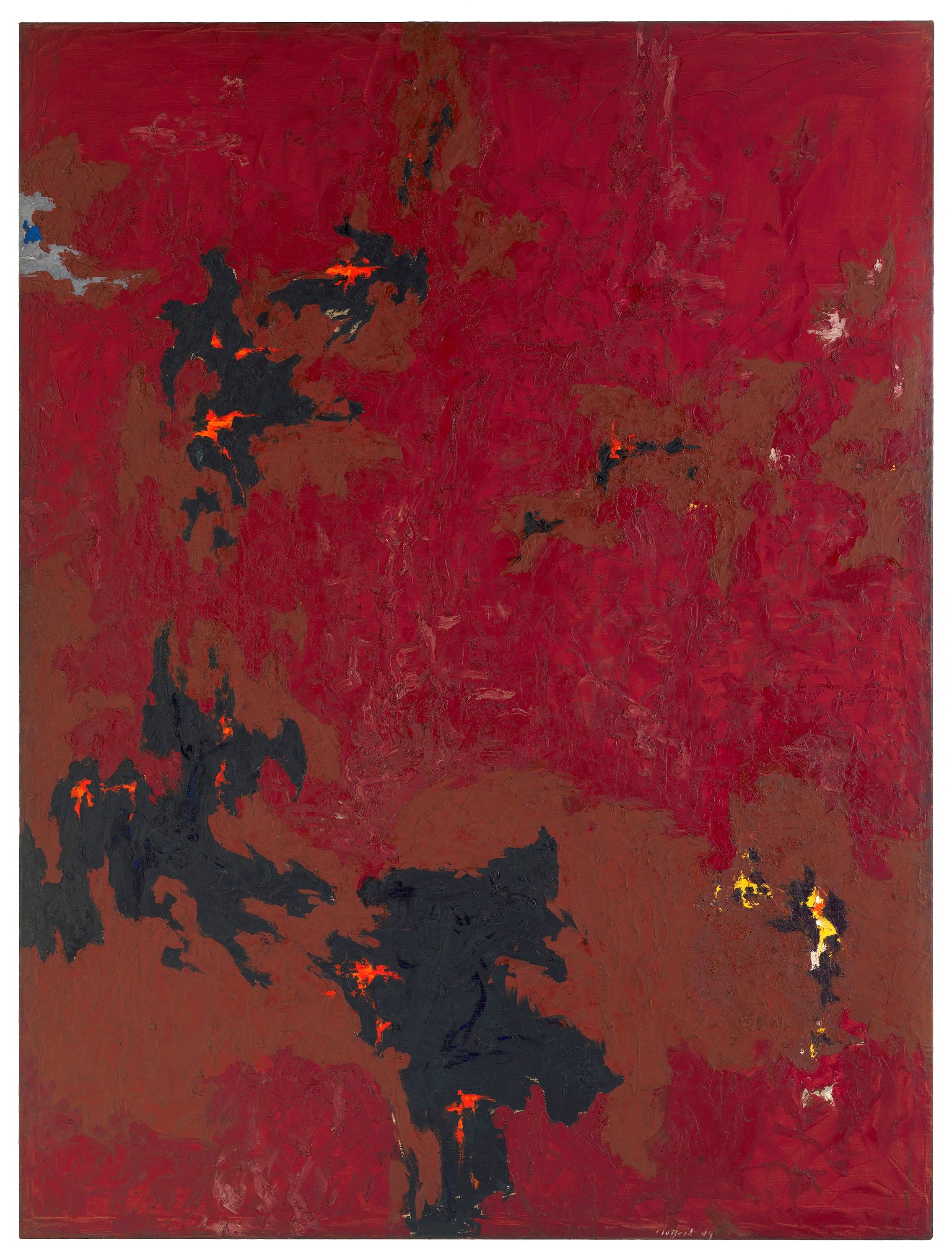

Lyn Grinstein, Jane Lang Davis’s daughter and the president of the Friday Foundation, says the fiery-looking Clyfford Still canvas going , PH-338 (1949-No. 2) (1949), has attracted particular praise from critics and curators such as David Anfam. “It’s requested constantly for loans,” she says.

The gift also includes two portraits by Francis Bacon. The Friday Foundation sold his Study for a Head (1952)—one of his celebrated “screaming Popes” inspired by Velázquez’s portrait of Innocent X—at Sotheby’s two years ago for $50.1 million. The foundation has since donated nearly half of those proceeds to Seattle arts organisations including the symphony, ballet and opera.

One of the works now coming to the Seattle Art Museum, Portrait of Man with Glasses I (1963), has a face so disfigured—a jumble of lenses and ears—that speculation about the proposed identity of the sitter has ranged from James Joyce to Mahatma Gandhi, with others yet speculating that it is London eye surgeon Patrick Trevor-Roper. In Study for a Portrait (1967), the subject is both Bacon’s friend Henrietta Moraes and his own recent paintings, pictured on the wall behind her.

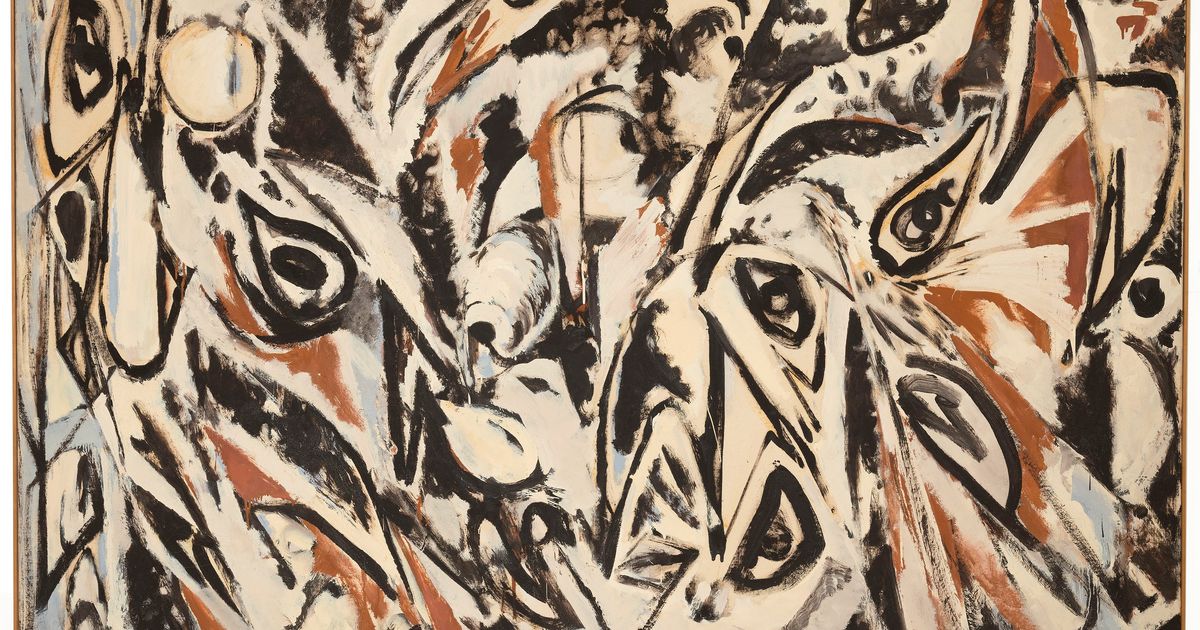

Helen Frankenthaler, Joan Mitchell and Lee Krasner, the only women artists in this gift, are all represented with large-scale works. Krasner’s Night Watch (1960) belongs to a visually turbulent series that the poet Richard Howard called “Night Journeys” because Krasner, suffering from insomnia, painted late at night in a reduced palette of blacks, browns and creams, unwilling to use more vibrant colours in artificial light.

Before this gift, the Seattle Art Museum did not own any works by Krasner, Still, Bacon, Giacometti, Gottlieb or Reinhardt.

The smaller donation to the Yale University Art Gallery consists of six works of art by Frank Kline and Mark Rothko, including an early Rothko from 1941-42 that shows the artist “moving out of his WPA figuration,” says Paulson. Grinstein says, “These are evolutionary works in the artists’ trajectories–we see them as academic study works.”

The Langs both served as trustees at the Seattle Art Museum, and it has already received important gifts of modern art from their friends Jinny and Bagley Wright, so the gift seems like a natural fit. But it was far from the only option, Grinstein says. “My mother was very hesitant to make that determination in her lifetime because she had been on the board of SAM and other museums, and sometimes they made decisions that put them in precarious financial situations. More than anything she wanted the collection to go to a museum that is healthy and in a good position to care for the work and love it like she did.”

To that end, the foundation is also giving the museum $10.5 million in cash to support the collection and its conservation. (Last year, it also gave the museum $2 million for a pandemic-related Closure Relief Fund and $2 million to endow an acquisition fund.) And terms of the donation “were very reasonable,” says the museum director Amada Cruz. She notes that the museum aims to show the works together every five years but can also loan out pieces or integrate them into other exhibitions. One idea, she says, is to explore the “calligraphic impulse” in New York School paintings, also drawing on the museum’s Asian art collection. Covid willing, the first full display of the gift will be this October.

Is there any chance, given the hetero or even macho white-male orientation of the group, that the museum could sell one of these works down the road to finance more diverse acquisitions? Grinstein confirmed that the contract includes a provision to prevent deaccessioning. “I have been on different museum acquisition committees, and I would be amazed to find any gift that doesn’t have that clause in it,” she says.

And asked about any other artworks left in the estate, Grinstein says there is nothing left to discuss. “We’ve given it all away. It was heartbreaking to think of those things in storage.”

Source link : https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/a-gift-of-blue-chip-modern-art-comes-to-the-seattle-art-museum