Wu Tsang, Anthem, 2021, installation view, at Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2021.

Wu Tsang, Anthem, 2021, installation view, at Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2021.

As the world of art broadens its borders and sets its sights on all realms of culture, ARTnews surveyed collaborations of various kinds for the August/September issue of the magazine. Stay tuned as roundups related to different categories—Art x Fashion, Art x Music, Art x Science, Art x Food, and Artists x Artists—join related feature stories online in the weeks to come.

Wu Tsang x Beverly Glenn-Copeland

Wu Tsang has used music in many different ways in her artworks: house and disco in dynamic video pieces driven by dance-minded soundtracks, for example, and old R&B in a multimedia work featuring footage of poet/theorist Fred Moten dancing in a regal red robe. But for an installation in the epic setting of the Guggenheim Museum’s rotunda, she turned to a singular figure from a realm of musical history still being told.

Wu Tsang, Anthem, 2021, installation view, at Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2021.

Wu Tsang, Anthem, 2021, installation view, at Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2021.

For Anthem, a commissioned work that opened at the Guggenheim in July and continued into September, Tsang collaborated with Beverly Glenn-Copeland, whose past in the annals of folk and new-age music has taken on a new kind of currency in recent years. As a Black transgender composer guided by voices that communicate most clearly outside the commercial sphere, Glenn-Copeland, now in his late 70s, came to the fore when his early albums and self-released cassettes like Keyboard Fantasies (1986) were given the reissue treatment. (The music website Pitchfork called the latter “strange and otherworldly” in a rave review last year.)

For the heart of the work, Tsang filmed Glenn-Copeland performing in Nova Scotia, where he lives, and assembled footage to be projected on a dramatic swath of silky white fabric descending from the Guggenheim’s oculus. To broadcast Glenn-Copeland’s transporting voice, she conceived a 14-channel speaker array distributed throughout the rotunda and up the museum’s spiraling ramps. As for that voice, Taja Cheek, who organized Glenn-Copeland’s 2019 performance at MoMA PS1, where she’s a curator, said, “there is a sort of purity to it. All these people from the art world and the music industry were stripped of their skepticism and all the ways they are judgmental, and put into a position where they were just there to listen to music that really touched them in a deep, foundational way. Everyone has a pure experience with Glenn’s music, and it’s really, really hard to come by.”

X Zhu-Nowell, the curator who organized Anthem as part of the Guggenheim’s series “Re/Projections: Video, Film, and Performance for the Rotunda,” said the new project was initiated in the midst of pandemic lockdown and roiling social crises last summer, when a suspended state of closure “allowed us as curators to rethink the practice of exhibition-making, not only because of the Covid-19 outbreak but also because of the cultural reckonings happening within the art world. It allowed us to ask questions such as: What is a museum space? Who is it for? What could new formats be for exhibitions? Can we create a space where one can take up the challenges and contradictions of context and historical conditions?”

As for Anthem and the way it fits into the lineage of other works that have made use of the Guggenheim rotunda, Zhu-Nowell said, “we wanted to complicate notions of monumentality and think about them in relation to collectivity and collaboration and coalition-building. We wanted to think about the rotunda as a social space or a site of assembly, a site for reflection and amplification.”

Ya Tseen’s album Indian Yard. Courtesy Sub Pop Nicholas Galanin x Ya Tseen

Ya Tseen’s album Indian Yard. Courtesy Sub Pop Nicholas Galanin x Ya Tseen

Sound has long been among the many materials favored by Nicholas Galanin, whose multivalent art ventures into painting, sculpture, textiles, totems, and just about any medium imaginable. But music rises to the top in Ya Tseen, a band with which he recently released an album on the venerated indie-music label Sub Pop (home to Nirvana, Sleater-Kinney, Beach House, Shabazz Palaces, and numerous other notable acts).

Though Galanin, a citizen of the Sitka Tribe of Alaska, has released music previously under aliases including Silver Jackson and Indian Agent, Ya Tseen’s album Indian Yard marks a next step for him in terms of musicianship and as a new nexus for the kind of work that his art-world followers have come to recognize. “Music has always been there, and I’ve never thought of music and art as separate, even if the way that people engage with them is different,” Galanin said. “I go back and forth in the process of figuring out what music is in relation to my life and my work, but it’s always been really important to me. I’ve just never had this sort of platform.”

Artwork by Nicholas Galanin that accompanies the Indian Yard song “At Tugani.” Courtesy Nicholas Galanin

Artwork by Nicholas Galanin that accompanies the Indian Yard song “At Tugani.” Courtesy Nicholas Galanin

For the soulful and psychedelically inflected electronic pop on Indian Yard, Galanin worked with bandmates Zak D. Wass and Otis Calvin III, as well as longtime collaborator Benjamin Verdoes. And from his Sitka, Alaska, home base, Galanin has commissioned collaborative videos as well, including one by Raven Chacon, a former member of the arts collective Postcommodity, for “Back in That Time.”

Galanin also made artworks to accompany each of Indian Yard’s songs for a deluxe vinyl edition paired with a book. “I had to revisit the songs from a whole other mindset to engage them after the record was done,” he said. “But I tried to move freely without being too anchored in process or aesthetic or imagery.” For “Light the Torch,” Galanin played with digitized self-portrait scans. “The music references a kind of battleground over how we define revolution—what it might mean for Indigenous communities and how we might respond if we want to see change,” he said. “The song represents action, whatever that action might be.” For “At Tugani,” a song named after his son, Galanin created an image of his son riding a tricycle among the stars. “It’s a generational creation story for him,” Galanin said of his two-year-old, whose name translates as both “something burns bright inside” and “gunpowder.” For “Close the Distance,” Galanin turned to a glitchy image of a woman in blue lingerie. “That song is a reference to seeking connection and desire across distances when we’re living in digital spaces in a digital age,” he said.

Speaking about working with Galanin both during and before the formation of Ya Tseen, Otis Calvin III said, “We pretty much just started working on songs, not thinking of anything huge—until we did. Nicky is different than most people. The isolation of Alaska allows him to think differently. It’s not that complicated: I go to Alaska and we just go into the studio and jam. We build songs. It’s easy to be mad-collaborative.”

Don and Moki Cherry performing, ca. 1973. Courtesy Cherry Archive/Estate of Moki Cherry Moki Cherry x Don Cherry

Don and Moki Cherry performing, ca. 1973. Courtesy Cherry Archive/Estate of Moki Cherry Moki Cherry x Don Cherry

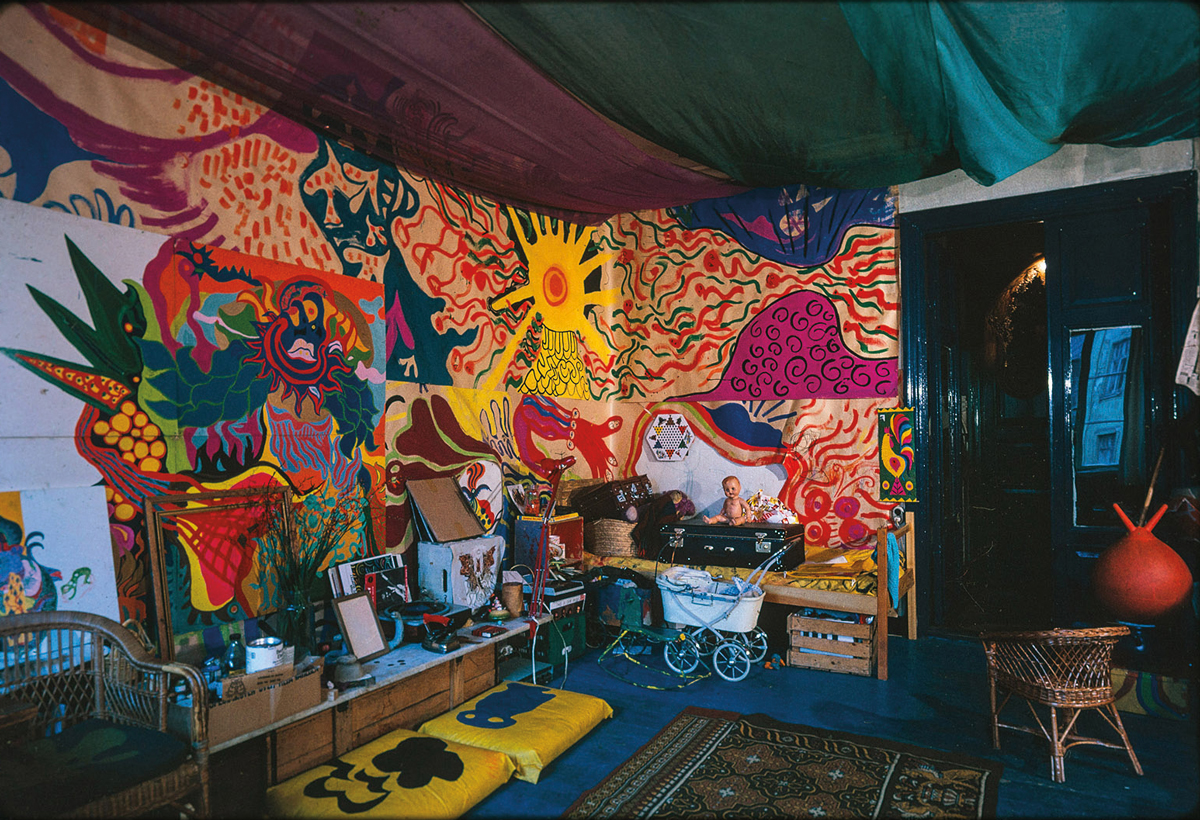

When Don and Moki Cherry started working together in the late 1960s, he was a young jazz trumpeter revered for his playing alongside Ornette Coleman and other visionaries, including Albert Ayler and John Coltrane, and she was a visual artist in Sweden known for work that orbited the realms of painting, tapestry, and fashion design. Not long after, the two became an ambitious and adventurous unit whose collaborative practice has only recently come in for full historical consideration.

This past spring, the New York–based curatorial platform Blank Forms mounted an exhibition in its Brooklyn gallery space and published a rigorously researched 500-page book devoted to the life and collaborative work of the couple, who legally married in 1978. Much of that work centered on music, but music on their terms was less mere aural accompaniment to life and more expansive spiritual and philosophical grounding for activities that reached into theater, pedagogy, and daily doings that took on the air of exalted ritual. As Blank Forms director Lawrence Kumpf wrote in the new book’s introduction, their shared endeavors with a lineage in theatrical Happenings and wide-ranging performance art “took Don’s music out of exploitative and commercially driven jazz circuits and integrated it into a total art and life project that broke away from convention.”

The Cherrys’ apartment in Stockholm in 1968. Photo Sven Åsberg/Courtesy Cherry Archive/Estate of Moki Cherry

The Cherrys’ apartment in Stockholm in 1968. Photo Sven Åsberg/Courtesy Cherry Archive/Estate of Moki Cherry

The book and exhibition both evolved from initial plans for a series of live musical performances that were waylaid by the pandemic. But they follow a trajectory that Blank Forms has been laying out with an increasingly ambitious publishing program (other books include volumes of essays and poetry by Maryanne Amacher, Thulani Davis, Catherine Christer Hennix, Joseph Jarman, and others) as well as exhibitions that present music-adjacent activities in well-curated ways (other shows have been dedicated to Graham Lambkin, Loren Connors, and Henning Christiansen).

In Don and Moki Cherry, the organization found a perfect subject. Asked how much art-historical attention has been paid to their collaborative practice in the past, Kumpf said “none at all.” And though Moki’s work as a painter and textile artist has seen some recognition, including a 2016 exhibition at Stockholm’s Moderna Museet, the newly focused spotlight puts her wildly creative work in different disciplines into a wider conversation. “It was great that her work was getting a little bit more traction,” Kumpf said, “but thinking through what the collaboration was and coupling them together hadn’t happened before. And it opens up a lot of interesting questions and parallels.” Among those are shared allegiances with art/music figures like La Monte Young and Pandit Pran Nath, the New York loft jazz scene, and Chicago’s Association for the Advancement of Creative Music (one of the subjects of the celebrated 2015 Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago show “The Freedom Principle: Experiments in Art and Music, 1965 to Now”).

The Blank Forms undertaking also led to two releases, on vinyl and CD, of archival recordings never heard before. And there are plans for more offerings of different kinds. As Kumpf said, “There is an incredible amount of unpublished material.”

Installation view of “Toyin Ojih Odutola: A Countervailing Theory” at the Barbican Centre in London. Photo Max Colson/Courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery Toyin Ojih Odutola x Peter Adjaye

Installation view of “Toyin Ojih Odutola: A Countervailing Theory” at the Barbican Centre in London. Photo Max Colson/Courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery Toyin Ojih Odutola x Peter Adjaye

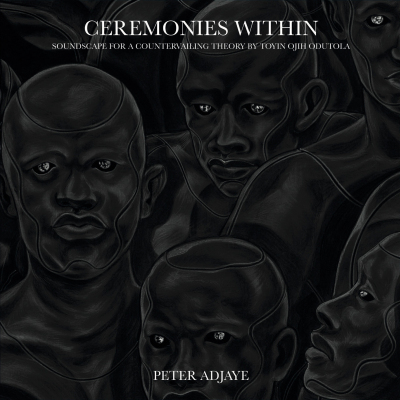

When Toyin Ojih Odutola decided she wanted something other than silence to accompany the drawings in her exhibition “A Countervailing Theory,” she turned to Ghanaian-British sound artist Peter Adjaye. Collaboration was nothing new to Adjaye, who had worked with sonic materials in concrete ways alongside his brother—celebrated architect David Adjaye—and others, blurring the lines between sound art and music. And Ojih Odutola had taken a particular liking to Adjaye’s work on Dialogues, a double-album release of recordings made for assorted buildings, chambers, and pavilions around the world. She asked him to imagine sounds and aural environments to amplify the landscapes in her drawings, surreal rock formations inspired by the Plateau State in Central Nigeria.

“I have synesthesia,” Adjaye told ARTnews about his working process. “When I’m talking about the visual realm, I’m thinking in sound. I’m activated by the visual but always thinking in response: What does that sound like? What sound would not be there? What would be there—and why?”

The cover of the album Ceremonies Within. Photo Nicola Hippisley

The cover of the album Ceremonies Within. Photo Nicola Hippisley

“A Countervailing Theory” opens in November at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., after premiering last year at the Barbican Centre in London and then showing at the Kunsten Museum of Modern Art Aalborg in Denmark. Each iteration features a multichannel speaker system designed for the respective space (12 channels for the Barbican, 21 for the Kunsten); the speakers emit ambient electronic sounds mixed with music composed in mind of what Adjaye called a Black West African aesthetic. Among the references in that music are Philip Glass and Ryuichi Sakamoto, but foregrounded in Adjaye’s composition, entitled Ceremonies Within, are the sounds of thumb pianos, bells, gongs, clay pots, and drums.

“She didn’t say, ‘You should use this sound or strings or synths.’ We never had that conversation,” Adjaye said about working with Ojih Odutola. “It was more like: What’s the atmosphere? What are the emotions for a series telling a narrative story across 40 different episodes? How do you get that across in a space that’s probably acoustically terrible?” (“Museums,” he added with a laugh, “are not designed to be acoustically interesting.”)

Ojih Odutola’s work in the exhibition centers on evocations of an imagined prehistoric civilization led by female rulers overseeing male laborers in an African homeland unmarred by colonialism. “It’s about flipping the script, mainly how I grapple with power and how it makes you clout-chase, perpetually brand yourself, and become obsessed with legacy building,” she said. “I know the story I made isn’t real, but it feels more real than this strange way of living I’ve had to acclimate to simply because a group of similar-looking and -minded people decided to mark the world.”

Adjaye said he hopes his aural background for the drawings can make Ojih Odutola’s conjured visual world even more real. “Sound can actually put you into a place, literally make your imagination create a kind of space,” he said. “The way I think about it is sculpting space and actual surroundings around a medium. And the collaboration with Toyin really is a great way for me to be able to experiment with a lot of ideas I’ve been playing with.”

Jacolby Satterwhite performing at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2016. Courtesy SFMOMA Jacolby Satterwhite x Nick Weiss

Jacolby Satterwhite performing at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2016. Courtesy SFMOMA Jacolby Satterwhite x Nick Weiss

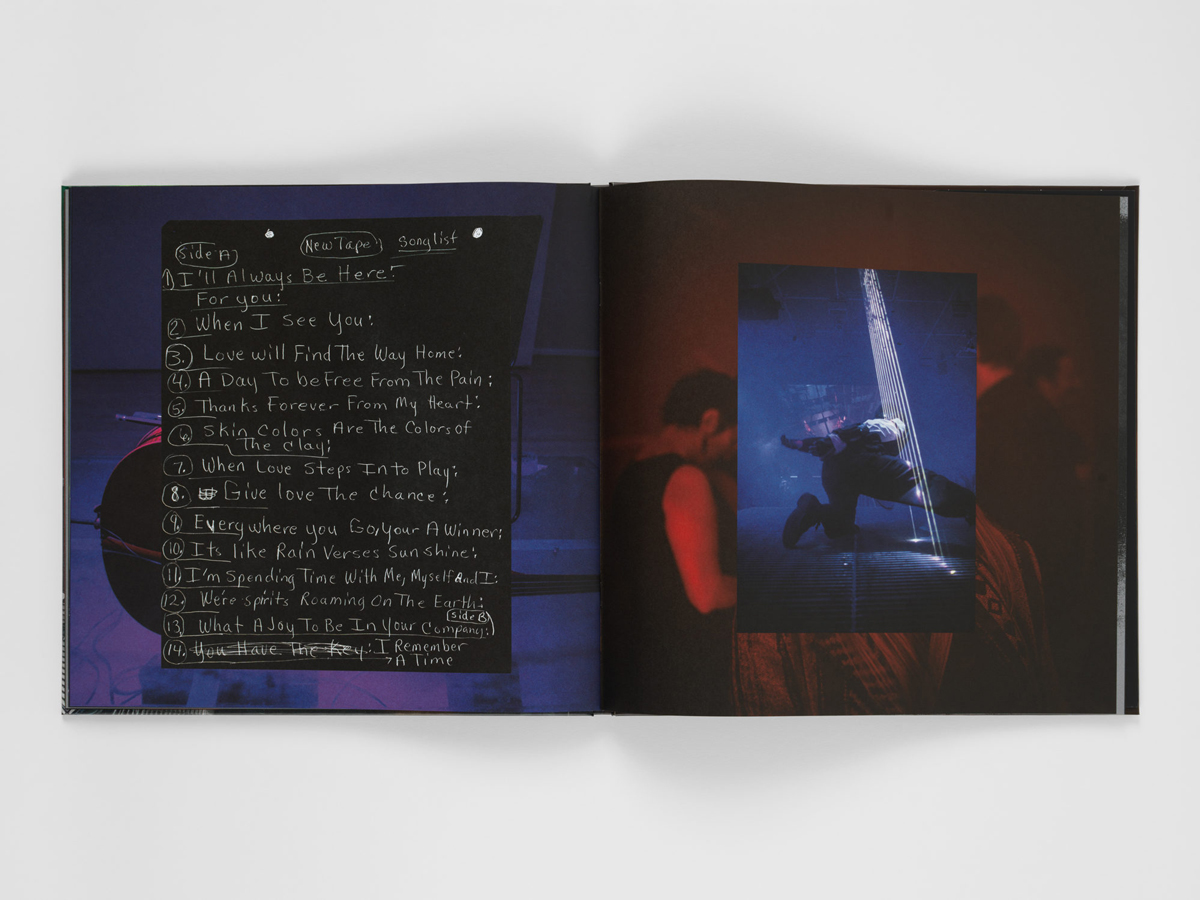

When video artist Jacolby Satterwhite’s mother died in 2016, she left behind a trove of cassette tape recordings on which she sang a capella invocations in unconventional styles. (She suffered from schizophrenia, and also made drawings of household items such as wet wipes, sugar cubes, and toothbrushes.) Satterwhite used those tapes as a starting point for making his mother’s voice live on after he formed the music duo PAT (short for Patricia, his mother’s name) with Nick Weiss, an electronic-music maker whose credits include the well-regarded early ’00s act Teengirl Fantasy.

“When I heard Teengirl Fantasy’s album 7 AM, I felt like teaming up with Nick would help me get the texture and the sound I wanted—that he would understand my instincts,” Satterwhite said. “And I was right.”

The artist and the musician began working together when Satterwhite was commissioned for a performance series at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2016. That work led to their 2019 album Love Will Find a Way Home, and sounds from that also featured the same year in an exhibition, “You’re at home,” at the sprawling Brooklyn arts center Pioneer Works, where PAT performed amid the variety of animation and video-art fantasias for which Satterwhite is best known. Some of the sounds also feature in “Spirits Roam the Earth,” a survey of Satterwhite’s work running August 14 into December at the Miller Institute for Contemporary Art at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Interior spread of PAT: Love Will Find A Way Home, an artist book by PAT (Jacolby Satterwhite and Nick Weiss) that includes two vinyl LPs. Photo: Dan Bradica/Courtesy the artists and Pioneer Works

Interior spread of PAT: Love Will Find A Way Home, an artist book by PAT (Jacolby Satterwhite and Nick Weiss) that includes two vinyl LPs. Photo: Dan Bradica/Courtesy the artists and Pioneer Works

“Ever since I was a kid, my inspirations were late ’90s music video directors like Chris Cunningham, Spike Jonze, and Michel Gondry—the canon of the experimental trip-hop lane of visual art,” Satterwhite said. “Sometimes when I was working on videos, I knew there was a sound that would push them forward, so I would go into the studio with Nick and we would figure out samples on synthesizers. When I was animating, I would listen to my mother’s vocals set within electronic music and instrumentation we would get from Patrick Belaga, an amazing experimental cellist, to add flavor. It was like a gumbo.”

Reached while making music in the desert of the American West, Weiss said, “the entire collaboration was super-organic. We clicked. And for as much as he knows about art, Jacolby knows just as much about music and music history, so that was exciting for me.” Their back-and-forth interactions, Weiss said, ended up influencing both their practices. “At first we were only working on the sounds, but as he started creating the visual world of the project,” Weiss continued, “it started to influence the music. The two worlds aren’t so far apart, and they don’t have to be. Like everything in our time, work starts to collapse in a way that allows for so much cross-pollination that is already happening.”

A version of this article appears in the August/September 2021 issue of ARTnews, under the title “Art X Music.”

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-news/artists/art-music-collaborations-wu-tsang-nicholas-galanin-1234603678