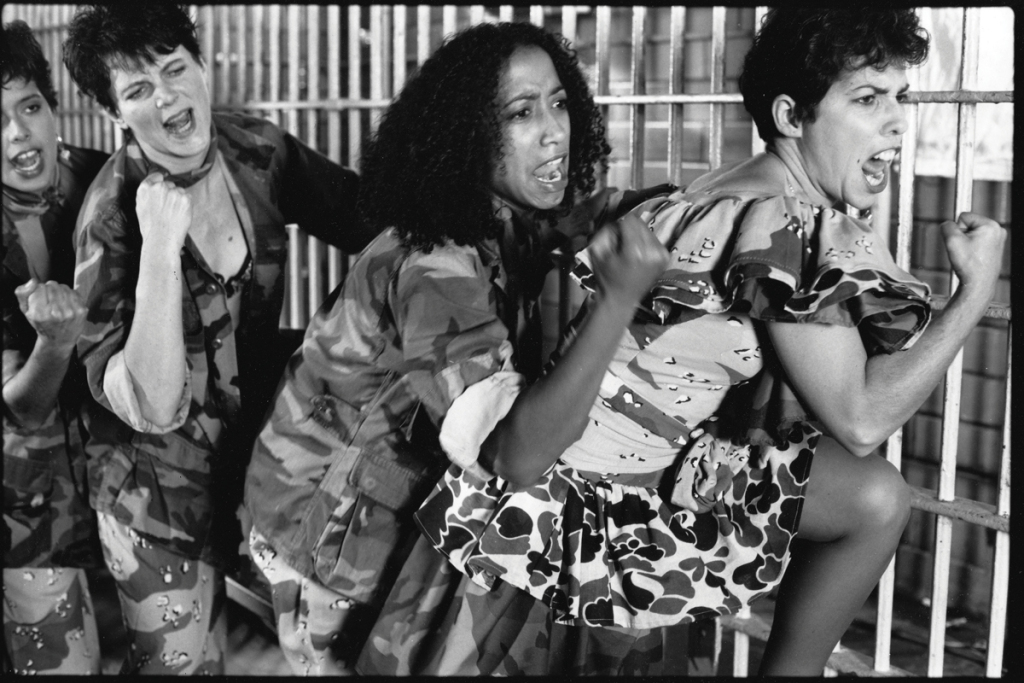

A still from Ela Troyano’s short film Carmelita Tropicana: Your Kunst Is Your Waffen (1994) featuring, from left, Livia Daza-Paris, Anne Iobst, Sophia Ramos, and Carmelita Tropicana. Photo Paula Court/Courtesy the artists

A still from Ela Troyano’s short film Carmelita Tropicana: Your Kunst Is Your Waffen (1994) featuring, from left, Livia Daza-Paris, Anne Iobst, Sophia Ramos, and Carmelita Tropicana. Photo Paula Court/Courtesy the artists

As the world of art broadens its borders and sets its sights on all realms of culture, ARTnews surveyed collaborations of various kinds for the August/September issue of the magazine. Stay tuned as roundups related to different categories—Art x Fashion, Art x Music, Art x Science, Art x Food, and Artists x Artists—join related feature stories online in the weeks to come.

Carmelita Tropicana x Ela Troyano

Siblings often share a private language that draws on common family histories and countless inside jokes and allusions, but rarely are such lines of communication as prominent as they are with the sisters Ela Troyano (an avant-garde filmmaker) and Alina Troyano (a performance artist better known as her character, Carmelita Tropicana). Though each has her own distinct art practice, the two have collaborated several times over the years. In certain performances, Tropicana has wryly joked that it was Troyano who first interested her in performance art—by suggesting she apply for a grant.

Their most notable collaboration is Carmelita Tropicana: Your Kunst Is Your Waffen, a short film from 1994 that was originally pitched to PBS as a two-part series. The film is a romp that looks at the life of Tropicana—both imagined and real—and three other women on the Lower East Side, ending with a musical number set in a women’s prison. Along the way, it explores stereotypes about women, Latinas, lesbians, and, most important, Latina lesbians.

A recurring element of their collaborations is the tropical fruit that Troyano sometimes sews into Tropicana’s costumes—to the disapproval of some observers. “When we first started doing fruits, people said, ‘Oh my God, how horrible—you’re being the stereotype of a Latina,’” Tropicana recalled. “Yes, we were doing that so we can go beyond it. And we were doing it with a wink so we could laugh at it. It’s very specific.”

Their latest collaboration is a podcast titled That’s Not What Happened, written and performed by Tropicana, and featuring Troyano as dramaturg and director. The project was initiated last September when the Soho Rep theater in New York invited Tropicana to a residency program, and since its first airing this past June, the 12-episode podcast has offered an adaptation of Tropicana’s memoirs that mixes monologues with impressionistic narratives to tell parts of the artist’s life story. The first season focuses on her early days in Cuba and stories of her grandmother and her father, as well as such influences she cites as 19th-century Cuban poet José Martí and the late Cuban-American queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz. The two sisters also collaborated with the celebrated musician Marc Ribot and his band Los Cubanos Postizos to create accompanying sounds for the show.

The podcast draws on stories shared among members of the family, “but there’s a discrepancy in how we all perceive what was going on in our memories,” Tropicana said. “It’s very intimate.” And through their own shorthand, the two sisters have come up with a language to share with others. “What I like about working with Ela is that she’s very visual, but also very analytical,” Tropicana said. “That’s not how my mind works. You want to work with people who are going to give you something you do not have. It inspires me when both of us are entwined in the work.” —Maximilíano Durón

Members of ruangrupa, the Indonesian artist collective curating the next edition of Documenta. Photo Jin Panji/Courtesy the artists Ruangrupa x The World

Members of ruangrupa, the Indonesian artist collective curating the next edition of Documenta. Photo Jin Panji/Courtesy the artists Ruangrupa x The World

Organizers of Documenta, the highly influential art festival that takes over Kassel, Germany, every five years, usually have to wrangle millions of dollars in funding, coordinate with hundreds of artists, and interface with countless administrators and politicians. By its very nature, the task has required willpower, decorum, and control. But the curators for the next edition—a nine-artist Indonesian collective called ruangrupa—have so far been given leeway for a more free-form approach to planning.

“A lot of the meetings are not productive—or not as productive as they could be,” said the members of ruangrupa, who prefer to be quoted as a single entity. “It’s really hard for us to have proper meetings. And then it’s frustrating as well for people to be in our meetings.”

Rather than sitting down with a set agenda for Documenta 15, slated to open in June 2022, the members said they have side-winding conversations from which they rarely emerge with fully formed ideas. Instead, epiphanies typically strike during WhatsApp chats and cigarette breaks—the in-between spaces where small talk can lead to big breakthroughs.

When it was announced in 2019 that ruangrupa would be heading Documenta, becoming the first collective ever to do so, it came as a surprise to many in the Western art world, where the group’s work has gone largely unseen. But in Southeast Asia, ruangrupa has emerged as one of the region’s most cutting-edge artist groups, thanks in part to its emphasis on togetherness and knowledge exchange. Formed in 2000, ruangrupa came together after the fall of Suharto, the Indonesian dictator whose decades-long authoritarian regime was accused of widespread corruption. Recalling their origin, ruangrupa said that, at the time, they experienced the “euphoria of ganging up together, congregating,” something they’ve sought to continue in their work since then.

Many of their initiatives involve gathering people in one space and seeing what happens. Among their most significant projects is Gudskul, an educational platform that they created with two other Indonesian collectives, Serrum and Grafis Huru Hara. Based in Jakarta, Gudskul has held programs abroad, including one at the 2019 edition of the Sharjah Biennial, where they offered “toolkits,” systems for recording and storing conversations about the concept of knowledge. A similar spirit imbued their presentation at the 2014 Bienal de São Paulo, held in a structure that blended architecture and sculpture.

Animating such cooperative endeavors is the concept of “lumbung,” which translates from the Indonesian as a sort of commons in which all is shared. And as planning for Documenta is still in progress, there is a possibility that, in ruangrupa’s hands, it will remain to a certain degree unfixed until the very end. The input of artist colleagues is essential to ruangrupa’s somewhat spontaneous work, so all its activities are in constant flux. “We cannot pretend that we know everything. There are a lot of things we don’t know,” the group said. “To collaborate with others—it’s kind of like making new friends from whom we can learn much, much more.” —Alex Greenberger

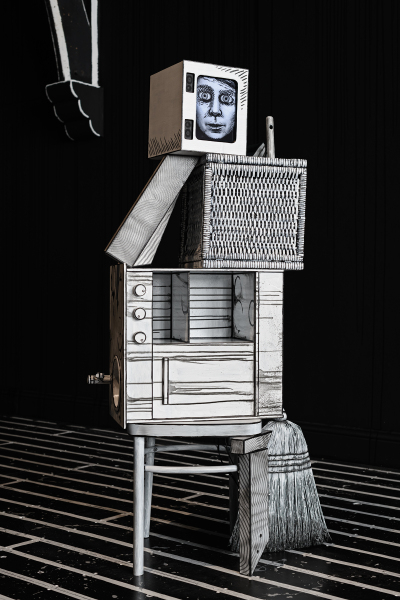

Mary Reid Kelley x Patrick Kelley  Installation image of Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley’s Rand/Goop from 2019. Photo Chris Ware/Courtesy the artists and Studio Voltaire, London

Installation image of Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley’s Rand/Goop from 2019. Photo Chris Ware/Courtesy the artists and Studio Voltaire, London

For artists who make a practice of collaboration, sometimes it takes just one project to change how they work together. Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley have been life partners since 2002, and artistic collaborators since 2008. Their surrealistic films, rich in wordplay and historical references, blend performance and animation; they star Reid Kelley as all the characters, and early on, the couple attributed the artworks solely to her. As Kelley’s involvement became more crucial, however, they began to cosign the works. Their most recent project, a commission for Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, relied to a greater degree on Kelley’s role as director, and made the two artists think differently about their process.

The Gardner gave the two artists a monthlong residency in the fall of 2019, and asked them to create an artwork in response to Titian’s painting The Rape of Europa to show in an upcoming retrospective. The Titian painting shows Zeus, as a bull, abducting Europa, who lies astride his back. “It’s just one of those incredible works,” said Reid Kelley, “where the more you look at it, the more it reveals, the more your perspective evolves.”

The film they created alternates between two settings. One of them looks like a stage for amateur actors, on which female characters from throughout history (all played by Reid Kelley) mime actions while a voiceover speaks limericks describing those characters. The other setting is an animated re-creation of the Gardner’s courtyard, where Europa (also Reid Kelley) responds to the limericks with a kind of pun called a Tom Swifty.

Usually, their process in making a film starts with Reid Kelley formulating both the subject and the script; Kelley then uses that as the basis for a cinematic concept. Since the new work was a commission, however, “we were both very much in on the ground floor of the collaboration,” Reid Kelley said. Kelley created a “church basement–type set” for the historical women, but re-creating the Gardner’s courtyard had a different level of complexity. Setting the film in the courtyard was crucial, Reid Kelley said, because they wanted it to “not just respond to this isolated masterwork, but also to the ideas of what a museum is.” Titian’s painting, she said, “is about the true foundations of civilization: theft, violence, coercion, and displacement. And there is a growing consciousness that that is what museums are showing us.”

To create that kind of resonance, Kelley turned, for the first time, to a handheld camera. “When you see that kind of shot,” he said, “it has this grounding in news footage and naturalism.” Meanwhile, Kelley’s role changed in an even more significant way. With Reid Kelley playing more characters than usual, he began to direct her more actively. “It dawned on us that we had to take better advantage of the perspective he has as director,” Reid Kelley said.

Added Kelley, “Every time we collaborate, there’s an element of evolution in our process.”

Reid Kelley said the couple still runs into the problem of people wanting to attribute the films to her alone. “People ideologically want and prefer a single author. People correctly identify the work as feminist and want a single female author.” —Sarah Douglas

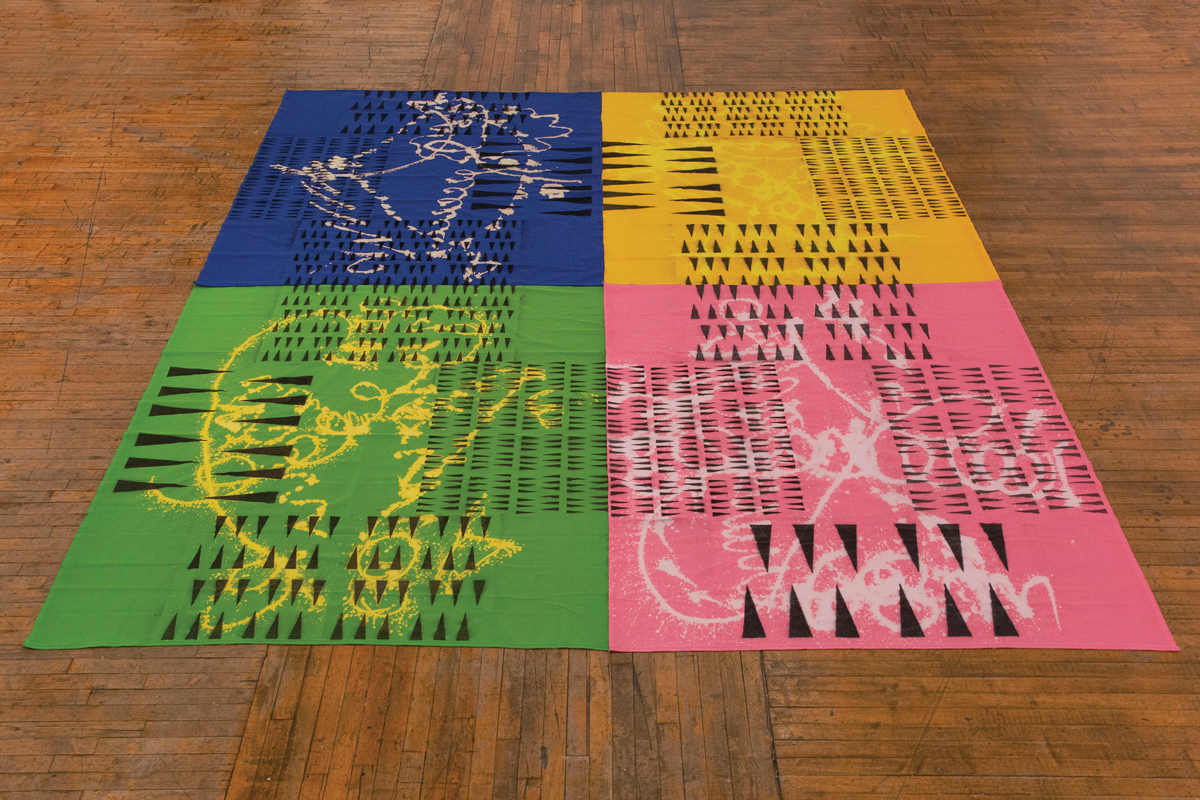

Polly Apfelbaum, Madeline Hollander, and Zak Kitnick’s collaborative artwork DROP CITY (2020). Courtesy La MaMa, New York Polly Apfelbaum x Madeline Hollander x Zak Kitnick

Polly Apfelbaum, Madeline Hollander, and Zak Kitnick’s collaborative artwork DROP CITY (2020). Courtesy La MaMa, New York Polly Apfelbaum x Madeline Hollander x Zak Kitnick

“Downtown 2021,” a show this past January at La MaMa Galleria in New York, took its name from the film Downtown 81, a time capsule from the city’s ultrahip Lower East Side of the 1980s. The movie combines both real and fictionalized footage of the milieu made famous by Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and countless others who toiled and roiled in the city’s streets, studios, and clubs. And the exhibition served as a second act of sorts, with a focus on independent galleries and art spaces (and the artists who populate them), including the feminist cooperative A.I.R., which has operated since 1972, and the newer-guard Brooklyn destination Pioneer Works.

Together, the artworks highlighted how the notion of “downtown”—as less a geographic than a generative locus—has expanded since then from Manhattan to far beyond; they illustrated a story about a constellation of grassroots galleries, artists, and curators aligning in mind of a common vibe.

One piece stood out as an exemplar of the show’s collaborative spirit: DROP CITY by Polly Apfelbaum, Madeline Hollander, and Zak Kitnick. Made expressly for the show, the 10-foot-square work comprises four squares of drop cloth individually dyed pink, gold, deep blue, and lime green, across which bleach was drizzled in patterns, and that were later stenciled with small black triangles. It looks like some sort of ceremonial quilt or robe reserved for unknown rites.

The artists conceived and executed it entirely over video, text, and phone while working in isolation during Covid lockdown. “It was both the most social and antisocial experience,” said Kitnick. “It was a reason to have an engaging conversation about anything besides the pandemic.” Apfelbaum, whose practice spans textiles, sculpture, and drawing, chose the drop cloth from her rich trove of materials and mailed it to Kitnick, along with a plan for the color scheme. Hollander, a former ballerina and choreographer (she directed the eerie Nutcracker-inspired dance in Jordan Peele’s 2019 film Us), created a series of gestural drawings. And Kitnick, a sculptor, painter, and installation artist who teases meaning out of quotidian objects, brought the parts together at his studio in a single session interrupted only by creative problem-solving. One insight: Kitnick squirted bleach through a squeeze bottle to apply the intended designs.

“The three parts became a whole,” said Apfelbaum. “It’s like, their hands become your hands. The idea and the doing are all equal.”

Apfelbaum came up with the title, imagining Drop City as a utopian community or a space for alternative thought, which seems befitting of La MaMa. And the act of collaborating served the three artists well. “This gave us practice in communicating and making a cohesive whole out of parts, making sure everyone’s happy,” said Kitnick. “With a piece like this you anticipate the possibility of failure or miscommunication, and we reserved the right for it happen.”

Such a fate was fortunately avoided, thanks in part to the fact that the three are longtime friends. (Apfelbaum and Hollander are actually second cousins, though they met only as adults.) “There was already so much mutual admiration between us all,” said Apfelbaum. “I don’t know if we could have pulled this off without it.” —Tessa Solomon

Young artists protest in front of the doors of the Ministry of Culture, in Havana, Cuba, in November 2020. Dozens of Cuban artists demonstrated against the police evicting a group who participated in a hunger strike. AP Photo/Ismael Francisco Cuban Artists x 27N

Young artists protest in front of the doors of the Ministry of Culture, in Havana, Cuba, in November 2020. Dozens of Cuban artists demonstrated against the police evicting a group who participated in a hunger strike. AP Photo/Ismael Francisco Cuban Artists x 27N

Since 2018, Cuba has restricted what artists can portray in their art and how they sell it by means of a controversial law known as Decree 349. In the biggest such collective action in years, around 300 protesters gathered outside the Cuban Ministry of Culture in Havana on November 27, 2020, to decry the country’s crackdown on artists. After Cuban officials said they would listen to demonstrators and then reneged, with Cuban President Miguel Díaz-Canel calling their demands a “farce,” an artist-led movement was born: 27N, named for the day of the initial protest.

In the months since, 27N has grabbed international headlines. Reuters, the South China Morning Post, and the New York Times all published reports on the November 27 protest, ensuring that fears of censorship within Cuba won’t be confined to the islands. High-profile figures have gotten involved: Tania Bruguera, a Cuban artist whose work regularly appears in major biennials and museums around the world, was detained by police as the protests raged; Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, currently among the most famous artists in Cuba, has been arrested numerous times in connection with 27N and the related San Isidro Movement. When he was taken by security officials in May 2021, Amnesty International labeled him a “prisoner of conscience.”

The sprawling and explosive nature of these protests caused historian Rafael Rojas to tell Cuba’s Bonita Radio, “this is the first time that artists and intellectuals in Cuba are challenging the constitution.” Artists and independent journalists in the country have attributed the movement’s success to the widespread collaboration among artists. In an interview, New York–based Cuban-American artist Coco Fusco said, “Together, there’s a lot more force than [among] people working individually.”

Unlike 27N’s older relative, the San Isidro Movement, which was formed in 2018 to protest the arrest of a young rapper and includes many self-taught and non-white artists, this movement comprises primarily people who “are white and upper-class, and part of the art establishment,” Fusco said. Thus, they can leverage their power in more public-facing ways. This past May, a group of artists—among them Bruguera, Tomás Sánchez, Sandra Ceballos, and Marco Castillo, a former member of Los Carpinteros—called on the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Havana to remove their works from view until Otero Alcántara was freed from the hospital where he was being detained at the time. (He was later released.) The museum declined to do so, though reports of 27N’s open letter made the international press.

Fusco said that 27N’s greatest achievement so far has been to reshape foreign journalists’ coverage of Cuba’s art scene. “The media attention is not on the grandiosity of the Cuban Ministry of Culture or how wonderful the art school is,” she said. “It’s all on repression, and that makes people outside the country think twice about what it is like when they get an invitation to Cuba.” —Alex Greenberger

A version of this article appears in the August/September 2021 issue of ARTnews, under the title “Artists X Artists.”

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-news/artists/artist-collaborations-ruangrupa-carmelita-tropicana-mary-reid-kelley-1234603681