Robert Indiana. Photo Joel Page/AP

Robert Indiana. Photo Joel Page/AP

There’s something off about a sculpture that Robert Indiana made for a sausage company in Wisconsin in 2017. BRAT, the gigantic work produced for Johnsonville Sausage’s headquarters in Sheboygan, looks at first glance like another Indiana classic. Much like his famed LOVE sculptures, it reconfigures a word—in this case an abbreviation for “bratwurst”—into a pair of two-letter rows and casts it in a stylish Clarendon typeface. But the sculpture lacks the tilted O of LOVE and the verve that comes along with it. BRAT is bold and eye-catching—and also oddly inert. Would an integral member of the Pop art movement really have signed off on a work so hokey?

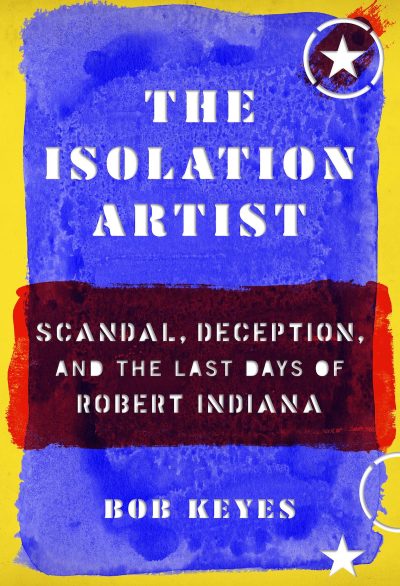

Bland art is one thing. Possible fakery is another, and indeed, there may be reason to doubt that Indiana produced BRAT himself. In his new book The Isolation Artist: Scandal, Deception, and the Last Days of Robert Indiana (Godine), journalist Bob Keyes enlists experts to assess various artworks attributed to Indiana, including BRAT. “It’s not something he ever would have done,” art historian John Wilmerding says of that sculpture. A former assistant even alleges that Jamie Thomas, who controlled Indiana’s estate by the time the artist died in 2018, personally faked the piece.

If BRAT was the only suspect work in Indiana’s oeuvre, it would remain an odd curio and nothing more. (The sculpture certainly would not have generated a standalone New York Times investigation otherwise.) Unfortunately, there are many others—including an Indiana-designed wine label that doesn’t look quite right, and a series about the alphabet with a questionable background, too. Add to this the multitude of lawsuits that swirled around the Indiana estate after the artist’s death, as well as the corrosive allegations of elder abuse, deceit, and broken promises that followed.

Keyes’s book aims to explore what really happened to Indiana at the very end of his life. With a cast of characters so long that the author has created a separate appendix for reference, The Isolation Artist presents itself as the ultimate guide to a very complicated legal drama. Readers are more likely to come away from this book with questions than answers—and if anything, this seems to be Keyes’s goal. Consider The Isolation Artist a case study in troublesome estate planning, showing how important it is for an aging artist to know their legal rights, and how necessary it can be to lay the groundwork early on for late-career financial upkeep.

Courtesy Godine

Courtesy Godine

Whether Indiana was the subject of fraud and abuse—and how much he knew about it all, if that was the case—is something we’ll likely never fully understand. “The end of Robert Indiana’s life was murky because, given how he’d lived, how else could it be?” Keyes writes.

After hitting it big in New York alongside the likes of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, Indiana decamped for the remote island of Vinalhaven, off the coast of Maine, in 1978. His time in Manhattan hadn’t been good for him. Unlike his Pop colleagues, Indiana wasn’t getting big retrospectives across the country. Moreover, he didn’t even own the copyright for LOVE, the famed work everyone knew him for. (Susan Ryan, Indiana’s biographer, has written that Indiana declined to include a copyright symbol on a poster version of LOVE when it was shown at Stable Gallery in New York in 1966. Indiana believed that the symbol took away from the graphic image he’d created.) By the time LOVE appeared on a U.S. Postal Service stamp in 1973, Indiana had seen only small financial returns from the work. Feeling maligned, Indiana relocated to the Star of Hope, a 19th-century lodge that became his home and studio. As the years went on, he largely cloistered himself there, ensuring that it would be difficult to see him.

A touted New York artist moving to Maine? During the 1980s, such a choice was a surprise to locals, who made pilgrimages to visit Indiana along with his cats and dogs. But the mercurial artist quickly alienated people around him. Add to this mess a 1990 lawsuit concerning alleged attempts by Indiana to solicit sex from young men (the artist was acquitted), as well as multiple failures to pay state income tax.

Everything turned around in the 1990s, when dealer Simon Salama-Caro began representing Indiana, bankrolling him through the Morgan Art Foundation. (A foundation in name only, Morgan Art is chaired by Robert Gore, who bought three works by Indiana at a show in London held by Salama-Caro. Beyond that, little is known about who runs Morgan Art.) Indiana sold the rights to LOVE to the Morgan Art Foundation, and in exchange, the artist received a steady stream of income. Meanwhile, Salama-Caro helped get Indiana’s work into major museums and galleries. Then, in 2008, publisher Michael McKenzie got involved, paying Indiana $1 million a year to produce HOPE, a similar sculpture to LOVE riffing on a word that had become Barack Obama’s calling card the year before. Having been pulled out of financial ruin, Indiana was back in the spotlight, with a Whitney Museum retrospective held in 2013. Then, sometime around 2015, he disappeared from the public eye entirely.

The Star of Hope. Photo Robert F. Bukaty/AP

The Star of Hope. Photo Robert F. Bukaty/AP

Keyes’s book largely revolves around those final years, when, rather mysteriously, Indiana—an artist who was “usually media-friendly and -savvy”—stopped giving interviews. Because Indiana rarely spoke to the media after 2014, it’s anyone’s guess what happened at the Star of Hope during that time. Some people in Indiana’s orbit suggest to Keyes that Jamie Thomas, Indiana’s final assistant, was effectively abusing the artist, keeping Indiana out of the view of reporters and friends alike. Sean Hillgrove, a former assistant to Indiana, recalls to Keyes that he could see into the Star of Hope from his own home. Indiana was “being held hostage” by Thomas, who by this point had assumed power of attorney over Indiana, Hillgrove wrote in his journal. Hillgrove told Keyes that he clandestinely arranged to give Indiana the number for an elder services company. But before Hillgrove and the artist could meet, Thomas allegedly changed the locks on the Star of Hope, and Indiana was forced to remain indoors.

Much of the media attention surrounding the Indiana estate has focused on lawsuits filed after the artist’s death by the Star of Hope Foundation, which manages Indiana’s estate. In those ugly lawsuits, the Morgan Art Foundation and McKenzie were accused of underpaying Indiana and making false art under his name, respectively—charges that both denied. (The suits were settled in 2021 for an undisclosed sum.) There are enough characters involved in these suits to put a prestige HBO drama series to shame, and even for those who followed the debacle closely, The Isolation Artist is likely to prove arcane. Still, Keyes’s book intrigues because of the mysteries at its core—particularly the ones surrounding Indiana’s death.

As with everything else in The Isolation Artist, even the most basic details of Indiana’s passing are up for debate. No one can agree on when or how Indiana died. Indiana may have died on May 18 or 19 in 2018, depending on who you ask, and he also had morphine, lorazepam, atropine, and isopropanol in his system—despite the fact that Indiana didn’t believe in Western medicine. Although independent forensic pathologists found no evidence of foul play, their report did say “his death appeared suspicious or unusual,” Keyes reports. “There are just too many questions,” Rob Potter, deputy sheriff of the Knox County Police Department, says.

Who was using Indiana, and for what reason, remains murky in Keyes’s book. For now, the conflict is still—sort of—churning on. Thomas is “out of the picture,” according to one lawyer; James Brannan, who became the executor of Indiana’s estate in 2016, is still fighting with McKenzie. What is clear is this: In his final years, there was a tussle over Indiana’s multimillion-dollar estate. Amid it all, the artist and his work seem to have been afterthoughts.

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/the-isolation-artist-robert-indiana-review-1234603336