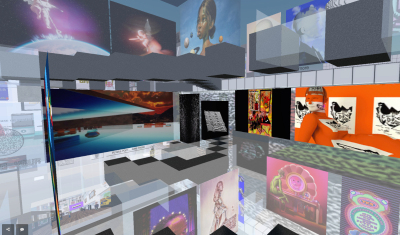

View of the exhibition “Natively Digital,” 2021, on Decentraland. Courtesy Sotheby’s

View of the exhibition “Natively Digital,” 2021, on Decentraland. Courtesy Sotheby’s

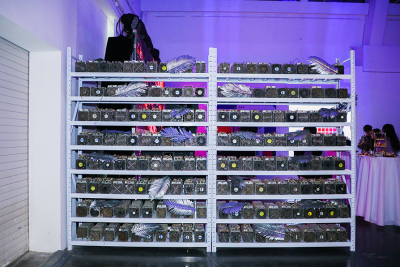

Is there a way to convey an artwork’s status as an NFT when exhibiting it in a gallery? When Simon Denny organized “Proof of Work” at Berlin’s Schinkel Pavilion in 2017, he displayed a CryptoKitty on a Bitcoin hardware wallet, a device used to secure blockchain assets offline. The goofy cat face appeared in grayscale on a simple little LCD screen, dwarfed by chips and wires signaling its relationship to a complex technological ecosystem. But in recent months, as exhibitions of crypto art proliferate, most curators display NFTs with monitors and projectors, just as they would any digital images not verified on the blockchain. “Virtual Niche: Have You Ever Seen Memes in the Mirror?” at UCCA Lab in Beijing last spring, billed as “the world’s first and largest physical crypto art exhibition,” included a “mining installation”—racks of hardware of the kind that expend prodigious amounts of processing power to write valuable lines of code—as a reminder of what gives the art on view its worth. But works by Beeple, Hackatao, Mario Klingemann, and others were shown on regular screens.

There’s a rich history of experimentation with presentations of new media art. Curators have devised ways to alter the gallery experience to accommodate interactive, nonlinear works. But NFTs tend to be still images or short videos, and few curators feel the need to seek out novel ways to show them: just mount a monitor and load the file on it. The technology of the NFT counteracts the mutability and multiplicity inherent to digital media by authenticating a single file. Anchoring a digital file on a monitor in a gallery and blowing it up to full-screen reinforces this artifice of objecthood by giving the image presence and heft. Ironically, the version of a work seen in a gallery may not be the NFT-backed one. Since most NFTs are traded on marketplaces that impose a 50MB size limit on files, artists sometimes need to create higher resolution display copies for big screens.

View of the exhibition “Virtual Niche,” 2021, at UCCA Lab, Beijing, showing the mining installation. Courtesy Block Create Art

View of the exhibition “Virtual Niche,” 2021, at UCCA Lab, Beijing, showing the mining installation. Courtesy Block Create Art

On March 25, the day before “Virtual Niche” debuted in Beijing, Superchief NFT opened in New York—a gallery with six flat-screen monitors and a few projectors that calls itself “the world’s first physical exhibition space dedicated solely to NFT artwork.” The phrase “physical exhibition” and its variations—used to promote Superchief NFT, “Virtual Niche,” and many other shows that cropped up as NFT sales exploded—seems misleading, or at least like a case of misplaced emphasis. Yes, these venues are “physical”—but so is my apartment, where I usually look at NFTs. The difference is the one-to-one ratio of devices to artworks. There are more screens at the “physical exhibition” than there are in my home, and they’re bigger, and they’re owned by someone other than me. When it comes to painting and sculpture, the “physical” aspect of the gallery means you’re looking at the real thing, not a reproduction. But that’s not the case with NFTs. What “physical” actually indicates is that the venue is a destination—I travel there to look at NFTs with other people. The “physical exhibition” is, more often than not, an occasion for a promotional event. It brings people together to make hype.

YAFA Csefar, World Computer, 2021, digital image. Courtesy Foundation

YAFA Csefar, World Computer, 2021, digital image. Courtesy Foundation

Superchief NFT is the latest in a network of galleries under the Superchief brand, the first of which opened in Williamsburg in 2012. These galleries sell work influenced by graffiti and comics, as much crypto art is. They aspire to be highbrow for the hypebeast, aligned with the collection of rare sneakers and other collectibles that are released in drops—a model adapted for sales of NFTs. Digital and storefront models of commerce mutually influence each other. Most gallery displays of NFTs have been linked to auctions or other sales. “Virtual Niche” was a showroom of sorts, held at UCCA Center for Contemporary Art’s platform for corporate partnerships, sponsored by DAOs and crypto investment funds and featuring works from “Asia’s first crypto art brand.”

On June 19, Superchief NFT hosted a one-day exhibition titled “Digital Diaspora” in collaboration with NFT marketplace Foundation. The show was organized by artist, curator, and activist Diana Sinclair. Stylistically diverse but united under the banner of Afrofuturism, the works were primarily fantastical portraits, images of Black princesses and goddesses. Drawing on the aesthetics of propaganda posters, Lyonna Lyu’s Tangiential Asmara in the Present depicts two women with third eyes open, overlooking an Eritrean skyline. In World Computer by Yafa Csefar, a bust in profile floats in space, with silicon nodes and cords connecting the bald head to planets. In a collaboration with Itzel Yard titled New Era Pending (Afro Netrunners IV), Sinclair’s own video self-portraits were animated by the syncopated blinking of Yard’s generative ASCII patterns. There were seventeen works in the show, so they had to share Superchief’s six monitors. They danced around the screens, cross-fading in and out of one another—all the portraits and styles mingling in an approximation of communal spirit.

View of the exhibition “Digital Diaspora,” 2021, at Superchief NFT, New York, showing work by Latashá. Courtesy Foundation. Photo Ramie I Nasser-Ahmed

View of the exhibition “Digital Diaspora,” 2021, at Superchief NFT, New York, showing work by Latashá. Courtesy Foundation. Photo Ramie I Nasser-Ahmed

From June 3–10, Sotheby’s held an online auction of NFTs called “Natively Digital” and presented the lots at its headquarters in New York and London. Flat-screen monitors hung at even intervals, sometimes varying in dimensions and orientation. The vibe at Superchief NFT may have been more youthful than the one at Sotheby’s, but the exhibition design strategies of the two venues were roughly the same. “Natively Digital” was a group sale of twenty-eight lots, following the house’s first NFT auction in April of a suite of works by Pak. The selection aimed to represent the breadth of NFT production. There were pieces connected to crypto art history, like a CryptoPunk avatar—the highest-selling lot—and Kevin McCoy’s Quantum (2014–21), acknowledged as the first artwork tokenized on the blockchain. There were also works by Lethabo Huma, Serwah Attafuah, and other emerging digital painters with strong sales records. “Natively Digital,” like the Pak auction, responded to the tastes and values of the crypto art community, rather than looking to Sotheby’s modern and contemporary department for ideas about what matters.

View of the exhibition “Natively Digital,” 2021, at Sotheby’s, New York. Courtesy Sotheby’s Courtesy Sotheby's. Photo Julian Cassady

View of the exhibition “Natively Digital,” 2021, at Sotheby’s, New York. Courtesy Sotheby’s Courtesy Sotheby's. Photo Julian Cassady

In a bit of outreach to reinforce this crypto-forward attitude, Sotheby’s created a digital replica of its London galleries in Decentraland, a virtual world that runs on the Ethereum blockchain. Some NFT collectors display the works they own in Decentraland, and entities like the Museum of Contemporary Digital Art have branches there. A “physical exhibition” often shows versions of NFTs, but Decentraland is as close as a display platform can be to an authentic environment for them. Parcels of virtual land there are registered as NFTs and sold for an in-world cryptocurrency. Installing art NFTs on these land NFTs means calling up the verified files. A show on a decentralized app like Decentraland is ephemeral in the same way a gallery show is. A site like Epoch Gallery or New Art City accumulates new shows like branches on a tree, whereas parcels of NFT-backed land are limited. Works get swapped out and shows go away, lost unless documented with screenshots.

At the Sotheby’s plot in Decentraland, an auctioneer in a top hat greeted people at the door, flanked by a CryptoPunk avatar and McCoy’s Quantum. The rooms inside were meticulous copies. Even the heads of the track lighting were reproduced, a useless detail in the undifferentiated brightness of virtual space. In a clever touch, the JPGs and MP4s were placed in black frames, as photographs would be installed, so they didn’t just cling to the walls as art often does in Decentraland’s exhibitions.

König Galerie’s venue on Decentraland, with a virtual sculpture by Manuel Rossner. Courtesy König Galerie

König Galerie’s venue on Decentraland, with a virtual sculpture by Manuel Rossner. Courtesy König Galerie

Other institutions have built their own outposts in the metaverse. Berlin’s König Galerie launched a space in Decentraland in March with the exhibition “The Artist Is Online,” as part of a new digital art program. The virtual gallery was designed by artist Manuel Rossner as a replica of the Berlin space, a brutalist church that König acquired in 2015. Rossner’s digital sculptures tend to be swooping, tubular shapes, volumetric brushstrokes made with gestures in VR painting software, rendered in bright, simple colors to catch the eye in virtual space. One of these punctures the virtual König, knocking a few of the gray-brown bricks out of the second-floor wall and corkscrewing up around the apse.

Rossner’s bold gesture creates some visual interest in an environment that is otherwise flat. The church is a remarkable space, both in Berlin and Decentraland, and the JPGs struggle to distinguish themselves there. The most appealing piece in the show was another work by Rossner—Drop Sculpture, an animation of a crinkly, gelatinous purple pillow tumbling the stairs into a lemon-colored room. Installed on the brick wall, the MP4 file seems to carve out a niche, a gateway to another space with its own virtual volumes.

View of the exhibition “Proof of Art,” 2021, on Cryptovoxels. Courtesy Francisco Carolinum

View of the exhibition “Proof of Art,” 2021, on Cryptovoxels. Courtesy Francisco Carolinum

Decentraland’s main competitor is Cryptovoxels, another decentralized app that runs on Ethereum and parcels land as NFTs. But all its architecture is cobbled from voxels—volumetric pixels, cubes that represent space on 3D space on a grid. As a virtual counterpart to its exhibition “Proof of Art: A Brief History of NFTs,” the Francisco Carolinum in Linz, Austria, bought parcels of land in Cryptovoxels and built a tower there. (The aforementioned “Digital Diaspora” also has a version in Cryptovoxels.) The Digital Francisco Carolinum, or DFC, is a tall, narrow space, with floors connected by floating staircases. It is packed tight with works by thirty-two artists, many of whom go by monikers like REEPS100 and Flufflord. The walls are translucent, so the mishmash of color and movement sometimes overlaps with images from galleries across the street.

Immersed in the noise of Cryptovoxels, DFC reflects the present of NFTs. But “Proof of Art” at the Francisco Carolinum points toward a longer history of digital art through the inclusion of works that predate the blockchain: Lynn Hershman Leeson’s A Commercial for Myself (1978), which portends social media’s mandate of self-branding; Nam June Paik’s Canopus (1990), an installation of six monitors affixed around the circular hub of a satellite to materialize paths of transmission; and a plotter drawing of interlocking squares, programmed by Herbert W. Franke in 1979–80. There are also works of blockchain-based art that predate this year’s NFT boom, like the tokens Jonas Lund and Sarah Mehoyas (Jonas Lund Token and Bitchcoin, respectively) developed to let collectors invest in their work, and Harm van den Dorpel’s dark, melancholy generative screensaver Event Listeners (2015), which MAK Vienna bought with Bitcoin in the first-ever museum acquisition on the blockchain.. Unlike most crypto art exhibitions, “Proof of Art” is not a commercial show. DFC doesn’t replicate Francisco Carolinum because there’s less of a need for branding. Visitors to the museum can visit Cryptovoxels via customized computer displays with limited interactivity, a familiar tactic of new media art exhibitions that seems to function as an inviting bridge between the two parts of the show.

View of the exhibition “Proof of Art,” 2021, at Francisco Carolinum, Linz, showing a terminal with access to the show’s virtual counterpart on Cryptovoxels. Courtesy Francisco Carolinum

View of the exhibition “Proof of Art,” 2021, at Francisco Carolinum, Linz, showing a terminal with access to the show’s virtual counterpart on Cryptovoxels. Courtesy Francisco Carolinum

The approaches to online exhibitions of NFTs have been more varied than presentations in galleries or on decentralized apps. Maybe it’s because conforming to expectations of physical space—or strict simulations of it in the blockchain-based metaverse—limits the imagination. Or maybe it’s because the artists and organizations who create online exhibitions have a deeper engagement with digital art, whereas the entities working in galleries and decentralized apps have come to it fairly recently, driven by commercial motivations. As the novelty of NFTs wears off, shows will need more than claims of “first” to attract attention. Perhaps that will lead to more sophisticated and innovative approaches to exhibition design.

Read part one of this article, on online exhibitions of NFTs.

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/nft-exhibitions-galleries-metaverse-1234602008