This article was featured in our Art Market Eye newsletter. For monthly commentary, insights and analysis from our art market experts straight to your inbox, sign up here.

I write this while quarantining in the UK, having returned from France in September—such is the nature of international travel in 2020. It is a chance to reflect on the art market that I have followed closely for over three decades. Looking back over this period, I am amazed by how it has changed, notably since I started working for The Art Newspaper in the late 1990s.

At that time I was living in Japan, then suffering in the aftermath of the baburu jidai or “bubble period” during which everything soared—from real estate to art, particularly Impressionist. That was a time when Japan’s real-estate bubble was so irrationally exuberant that the ground under Tokyo’s Imperial Palace was said to be worth more than the whole of California!

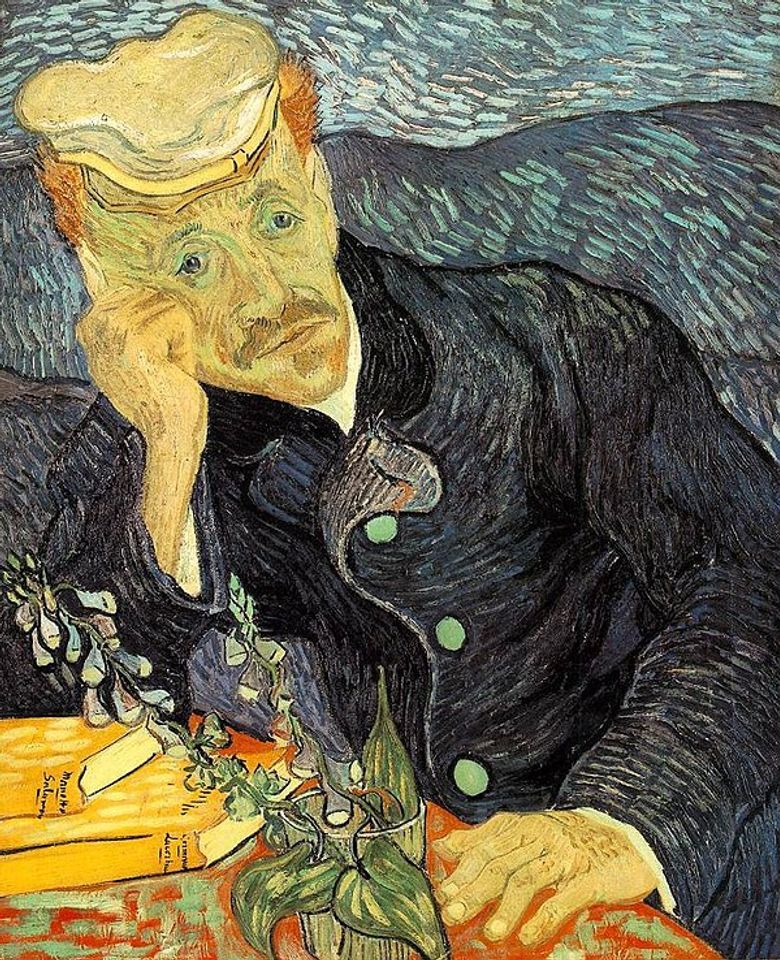

The Japanese were crazy for paintings and at the top of the market in 1990 the country gobbled up some $4bn in art—notably half of all Impressionist art put up for sale that year. The peak was when Van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr Gachet (1890) sold for a stunning $82.5m, bought by the industrialist Ryoei Saito, who then announced he wanted to be buried—and cremated—with it.

That never happened, as Saito went bust and the work changed hands, but the elusive portrait has never been seen in public again. That price, which stunned the world at the time, has been bested many times over since then, most famously/infamously in 2017 when the Salvator Mundi made $450.3m at Christie’s.

Such extraordinary price inflation is probably the most staggering phenomenon that has defined the art market since 1990. Many times I have considered it as a “bubble” without it ever really being pricked. Even after the global financial crisis of 2008-09, art recovered astonishingly quickly.

“It is difficult to believe that when I started out contemporary art was still a minor, specialist area.”

Today, with a pandemic seeming sure to bring a global recession, art has still proved surprisingly resilient, at the top end at least. The reason? I believe it is primarily because of the polarisation of wealth, with a few ultra-wealthy (and I mean really, REALLY rich) individuals battling for a few trophies. Add to this an emphasis on acquiring “safe” tangible assets, and you have a classically lucrative supply-and-demand situation.

The world I started writing about was vastly different then, and one of the greatest shifts I have observed is the change of focus in art categories. It seems difficult to believe today that queues used to form before the opening of the Grosvenor House Art and Antiques Fair (remember that?) or the Olympia fair in London, or the Biennale des Antiquaires in France. Buyers pounced on lacquered 18th-century commodes or inlaid consoles or porcelain perfume burners or Chippendale carvers…to go with their soft-focus Renoir paintings in ornate gilt frames.

This seems a world away now. The headlong rush into Modern and contemporary art has carried all before it, and it is difficult to believe that when I started out contemporary art was still a minor, specialist area. After all, the first contemporary art evening sale, at Sotheby’s in London, was only in 1993.

Middle Eastern emergence

Middle Eastern emergence

Certainly, the opening up of massive new markets in the Middle East, Russia and China shattered that cosy world of European and US-centred art and iconography. One of the defining moments of my career (if you can call it such—it really happened more by accident) was going to Qatar to interview Sheikh Saud Al-Thani, at the time the biggest art buyer in the world. Having arrived in Doha with no fixed appointment, I didn’t dare leave the hotel in case I was suddenly summoned.

This did happen early one morning after three days, and I raced to dress and slap on some make-up. I found myself in a Maybach (a car I hadn’t even heard of, but then I’m not into cars) hurtling through the desert to his country “farm”. Here, I saw the rare gazelle breeding programme, aviaries for birds of paradise, thousands of antique bicycles and hundreds of vintage cars, as well as some of his momentous purchases: the Constable-Maxwell cage cup (a rare piece of 4th-century Roman glass) and the Jenkins Venus, a Roman sculpture from Newby Hall in Yorkshire, along with Art Deco furniture bought by the Maharajah of Indore, natural history specimens…on and on, and all stored in quite unsuitable conditions in dusty hangars.

The following year I was tipped off at Tefaf Maastricht that Sheikh Saud had been sacked after “misappropriation” of government funds, and over a series of articles, The Art Newspaper team unravelled his alleged misdeeds. Ultimately rehabilitated, he died in 2014 but his legacy lives on in the magnificent Museum of Islamic Art in Doha.

Auction houses evolve

Auction houses evolve

Working as a journalist, one of the things that strikes me is how the auction houses have evolved. Two decades ago, the London headquarters were still quite casual: I could wander into their press offices to get information, for example. Sitting down at a desk to make some notes, I once nonchalantly turned over a piece of paper to find a list of journalists and character comments on each one, myself included! (It wasn’t too bad…). I could call specialists directly if I wanted information. All that has changed: Sotheby’s, Christie’s et al. are now totally corporate, with information carefully massaged and managed before it is sent out. And don’t even think of trying to contact an employee directly; every call must be conducted to the sound of a press officer gently breathing down the line in the background.

Slicing and dicing

One aspect of the art market I now find rather depressing is the commodification of art. I have visited storage facilities in Singapore, Luxembourg (where I attended the splashy inauguration of Le Freeport, prop. Y. Bouvier, and we all know what happened there) and in New York. I have seen stacks and stacks of crates piled up in armoured strong rooms. I find it difficult to believe that artists ever create art for it to be packed up and left in storage, waiting for it to go up in value, or for other reasons such as tax “optimisation”.

A recent trend is fractional ownership, in which art is sliced and diced into marketable slivers (not physically, of course). Although many schemes claim that their aim is to democratise art ownership, my fear is that, in the rush to treat art purely as an asset class, it will become an extension of the luxury goods industry. Perhaps one positive aspect of the pandemic (and goodness knows, there are few) will be a return to values that we used to prize in art—symbolic, aesthetic, challenging. Not just something to buy, store and re-sell.

Source link : https://www.theartnewspaper.com/comment/bubbles-sheikhs-and-the-freeport-frenzy-georgina-adam-reflects-on-30-years-of-art-market-reporting