The US scholar and art historian Noah Charney says that scandal and shock in the art world, and the headlines they generate, are not just 21st-century phenomena channelled by publicity-hungry artists. “We tend to think of this as a [contemporary] phenomenon—that we need to shock in order to get attention. But there are elements of this in historical artworks as well,” he says.

Charney’s latest publication, The Devil in the Gallery: How Scandal, Shock and Rivalry Shaped the Art World, explores how numerous artists over the centuries have courted scandal using the “shock factor” to promote their works. The book is divided into three sections: Scandal, Shock and Rivalry. “All three are ultimately beneficial to the course of art,” Charney says, outlining the central thesis behind his analysis.

The publication encompasses 31 case studies, such as the “monumentalising of scandal”, as he calls it, around Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937). Charney says it caused “a scandal when it came out because it revealed a scandal the perpetrators hoped would be forgotten”. (The Basque country town of Guernica was bombed in April 1937 by the Nazi Luftwaffe at the behest of Francisco Franco’s Nationalist forces, leading to hundreds of civilian deaths.)

“In colloquial terms, Caravaggio was a major-league asshole” Noah Charney

Meanwhile, the artist Édouard Manet’s depiction of sex workers in paintings such as Olympia (1865) subverted societal attitudes. “Engagement with prostitutes was the norm in 19th-century Paris, but it was simply not something one talked about,” Charney writes. He explains how one journalist at the time lamented the painting’s “inconceivable vulgarity” while the novelist Émile Zola called the notorious work Manet’s masterpiece. Other less scandalous but nonetheless revealing topics include how and why artists such as Jeff Koons employ armies of assistants to complete their works, pulling away the curtain to show the Svengali directing a battalion of staff.

Crucially, Caravaggio anchors the book, straddling all three sections. “Caravaggio’s life was full of rivalries; there were scandals that he didn’t court and he did a lot of things intentionally for shock value, so there is certainly overlap,” Charney says. He writes candidly that in “colloquial terms, Caravaggio was a major-league asshole”. But the 16th-century artist was also a very clever businessman, demonstrates the author.

Caravaggio’s Death of the Virgin (around 1601-06) used as the model for the body of Mary a prostitute that he saw dredged out of the Tiber River in Rome. Charney theorises that the artist intentionally made “indecorous” works disliked by church commissioners. Caravaggio would cannily keep the advance on his commission and then quickly sell the finished painting to a private buyer for far more money.

Today’s tabloid fodder is also discussed, such as the identity of the UK street artist Banksy, whose antics continue to enthral the wider public. “This is not really scandal or shock but it’s an intentional provocation—keeping his identity secret but then enjoying having people play the guessing game. I’m most compelled [to believe] that it’s Robert Del Naja from the group Massive Attack,” Charney says.

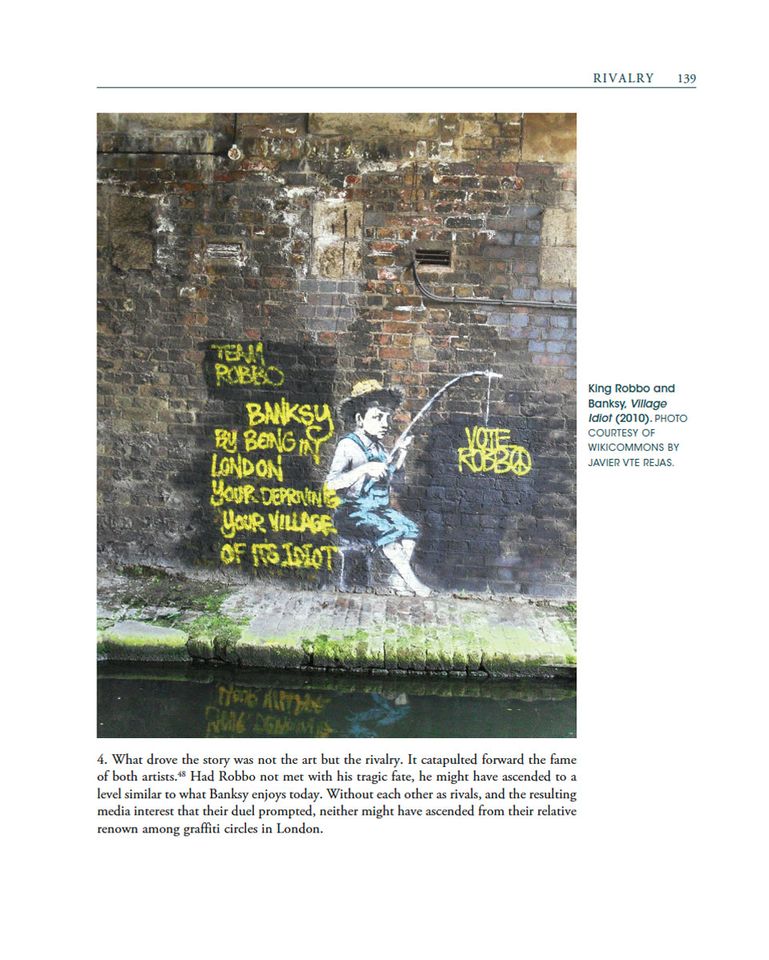

He elaborates on the forgotten feud between Banksy and another UK graffiti artist, King Robbo, who died in 2014. “Banksy is now a household name, but back in 2009, in the Camden Town neighbourhood of London, King Robbo was the monarch of graffiti art, and far more famous,” Charney writes.

Both street artists engaged in a series of tit-for-tat overpaintings (the text King Robbo daubed on a wall was turned into Fucking Robbo by Banksy, claims the author). “Not many people were interested in the graffiti art of either, really, but they liked this teasing back and forth. That was what hooked them,” Charney says, touching on the issue of how the public, or a willing audience, “rewards rivalrous behaviours”.

The most detailed and well-researched chapter tracks the fallout between the performance artist Marina Abramović and Ulay, her late former partner (the relationship ended acrimoniously in 1988 after an epic performance walk towards each other along the Great Wall of China). “I got through about 20 hours of interviews with Ulay but then he became ill. He also told me about his criminal [act]— how he stole a work of art [Carl Spitzweg’s The Poor Poet, 1839] from a Berlin museum as an artistic action.”

A contract was drawn up in 1999 that outlined how both artists’ joint oeuvre should be dealt with. Ulay subsequently sold his physical archive of their joint projects to Abramović for a flat fee, which included exploitation rights. But the arrangement turned sour. “What really concerned Ulay was his perception that Abramović was trying to rewrite history and airbrush him out of it,” Charney writes. In 2016, Ulay won a lawsuit proving that Abramović was in breach of the contract signed 17 years earlier.

“Bramante was nervous about his contemporary but thought Michelangelo would never be able to pull off a massive fresco” Noah Charney

The issue of whether all scandal is intentional, or just a question of drama around professional rivalry, is also tackled by the author. A famous clash of egos took place during the Renaissance when Charney argues that there would be no Sistine Chapel works by Michelangelo had the architect Donato Bramante not tricked Pope Julius II into assigning him the commission.

“The gist is that Bramante was nervous about his contemporary but thought Michelangelo would never be able to pull off a massive fresco, as he’d never worked in the medium,” writes Charney, resulting in possibly the greatest foot-shooting in art history.

Charney is also the author of The Museum of Lost Art (Phaidon, 2018), a compendium of masterpieces looted and destroyed over the centuries. “Everybody likes true crime [but] there’s a more limited audience for art; if you put the two together, then people will come for the crime and stay for the art,” Charney says. This populist, frothy approach marks him out. “It is very important to me to not treat art in a way that is at all elitist,” he concludes.

• The Devil in the Gallery: How Scandal, Shock and Rivalry Shaped the Art World, Noah Charney, Rowman & Littlefield, 200pp, £35 (hb)

Source link : https://www.theartnewspaper.com/interview/the-long-held-tradition-of-scandal-in-the-arts