Johannes Zoffany: The Family of Sir William Young, ca. 1767–69, oil on canvas, 45 by 66 inches. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

Johannes Zoffany: The Family of Sir William Young, ca. 1767–69, oil on canvas, 45 by 66 inches. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

Can statistics save art history from its most egregious blind spots and methodological limits? This is the question posed by Diana Seave Greenwald’s new book, Painting by Numbers: Data-Driven Histories of Nineteenth- Century Art, one that she answers with a carefully measured, continually qualified yes. Greenwald’s argument hinges on how she frames the problems facing art history in the first place, as a problem principally of scale. In her telling, art history, with its focus on case studies and comparisons, formal analysis, and institutional archives, is woefully limited in its scope, centered on a selection of objects that is too small and too singular to account for the majority of artistic production in any meaningful way. Greenwald uses the term “sample bias” to describe this endemic condition. Borrowed from the social sciences, sample bias occurs when a scholar studies a group of objects that is “both limited and misrepresentative.” Sample bias in art history is tricky to overcome, because it arises from art’s structural conditions: most objects made are never exhibited and far fewer are collected; as Greenwald puts it, “it is hard to account for artworks that one cannot see or study.”

Enter statistics and other quantitative methods, which from their inception have promised to bring such invisible populations and patterns to light—to transcend the individual and exceptional to elaborate the structural, social forces beyond the frame. Trained as an art historian and economist, Greenwald offers an argument that resonates most strongly with the newer field of digital humanities, especially the work of Franco Moretti, whose “graphs, maps, and trees” vividly visualize the minuscule number of books considered in the study of world literature. Following Moretti’s “distant reading,” which substitutes sweeping studies of entire genres for close readings of individual texts, what Greenwald calls “data-driven art history” promises not only to account for the majority of missing artworks but also to concretize historical context, to supplement if not contradict art history’s most sedimented assumptions about what information can be gleaned from an image. Painting by Numbers is organized to demonstrate how statistical analysis of large data sets can supplement the visual data of individual artworks with the visualization of social and institutional forces. Yet data-driven art history has it exactly backward, offering a performance of technological proficiency in place of a substantive transformation of the questions and evaluative categories that define—and confine—the field.

Painting by Numbers: Data-Driven Histories of Nineteenth-Century Art by Diana Seave Greenwald, Princeton University Press, 2021; 256 pages, $35 hardcover.

Painting by Numbers: Data-Driven Histories of Nineteenth-Century Art by Diana Seave Greenwald, Princeton University Press, 2021; 256 pages, $35 hardcover.

If Greenwald’s method might appear new to some, the objects of her study are about as canonical as they come: nineteenth-century oil paintings shown at decidedly official institutions (British Royal Academy, Paris Salon, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts) in Britain, France, and the United States. The method, she admits, determines the subject: these are periods and places where enough information exists to be analyzed. (Indeed, the things Greenwald wants to use data to consider—time, money, institutions that painstakingly document all the works shown at annual exhibitions—are those that tend to produce paper trails.) As Greenwald acknowledges, there are severe limits built into her data set: the sample excludes anything that is not an oil painting, and so it excludes contemporaneous artistic production in more popular modes; the focus on academies and official exhibitions effectively erases some of the most significant figures of the avant-garde (who by definition showed outside these institutions); and for the majority of works, Greenwald must rely on the title as the sole source of information about the painting’s content. To sidestep these issues, the author echoes her own argument about expansion; data-driven art history is valuable as one method, among many, for art historians to employ. To this end, she offers the data itself as a resource, with a long chapter detailing its compilation, numerous appendices of charts and graphs, as well as an online resource with the edited data. On its own, this is a worthy contribution to the historical record, representing more than a decade of work spanning her multiple degrees, post-doctoral fellowships, and grants, and incorporating the labor of those hired to code, compile, and run analysis—all this before Greenwald even began to unpack the evidence and assess the implications of the results.

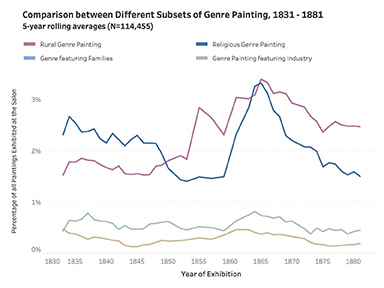

So, what is the payoff of this immense effort? The conclusions Greenwald offers range from the redundant, to the banal, to the unconvincing, to the incorrect. After a compelling introduction and the diligent chapter on data collection, Greenwald turns to three case studies to demonstrate what data-driven art history can do. To illustrate its revelatory potential, she addresses some of the most central themes of nineteenth-century Western art history: how industrialization, gender construction, and colonialism determine who gets to be an artist and what is represented in art. A chapter on landscape painting aims to unsettle the argument that romantic depictions of country life and peasant labor were made in response to the rapid industrialization, urbanization, and development that threatened this way of life. If this were true, Greenwald writes, the data would show that as conditions in the city worsen (as indicated by strikes and visible poverty), the number of paintings of pastoral images of the countryside would increase. Greenwald claims her data demonstrates the opposite: it was the “advantages” of modernization like cheap train travel and countryside artist communities rather than the “ills” of urbanization, proletarianization, and precarity that led to the (still statistically small) increase in rural genre painting—as if one could separate the developments and devastation wreaked by modernity.

A graph included in Painting by Numbers.

A graph included in Painting by Numbers.

Greenwald’s close study of the life and work of American painter Lilly Martin Spencer (1822–1902) results in the obvious observation that women artists lacked time, financial independence, access to education, and exhibition opportunities. A final case study tries to account for the striking absence of depictions of territories colonized by the British: “Explicitly named images of empire barely appear at the Royal Academy,” which Greenwald goes so far as to call “an apparent erasure or denial of empire at the height of imperial power and expansion.” This, she argues, is due to the intolerance of “extractive” institutions like colonialism within “inclusive” institutions like the Royal Academy. Greenwald uses a definition of inclusive institutions drawn from economics: those that are open to relatively wide participation, such as property rights, democratic elections, and courts that adhere to due process. This relative inclusion (to say nothing of structuring conditions of possibility), Greenwald contends, explains why images of empire do not overtly appear in the oil paintings at academic exhibitions: participants could not tolerate the brute reality, even implied existence, of colonial violence. Greenwald acknowledges (but then moves swiftly on from) two important qualifications: that images of empire abound in print culture (not included in her sample) and that the newfound wealth of those newly included in the Royal Academy was a direct result of colonization. Empire, in other words, was everywhere, the determining condition for wealth, art, taste, and image production in Britain. To argue the contrary, as Greenwald does, requires such a superficial and circumscribed analysis as to suggest that data here is operating to actively repress history rather than to probe history’s complex and multifaceted depths.

One can imagine a study otherwise, in which statistical data helps us better understand both apparent and invisible contradictions: to navigate how the visual, be it in the form of images or information, is far from self-evident and its interpretation is itself a contested and counterintuitive terrain. In fact, one doesn’t have to imagine this at all. This is how empirical methods are most often used in art history, specifically in the tradition to which Greenwald is most indebted: the social history of art. At another moment of disciplinary crisis more than fifty years ago, scholars like T.J. Clark, Linda Nochlin, and Griselda Pollock incorporated ideas from continental philosophy, Marxism, and feminism—and yes, also quantitative methods—to account for the historical and biographical conditions that determined categories like artistic genius, skill, and quality. Likewise, artists have mobilized data since at least the advent of institutional critique in the 1960s and ’70s, if not before: think of Dan Graham’s accounting of nouns and adjectives used in art magazines, Hans Haacke’s visitor polls, and activists like the Art Workers’ Coalition, which aimed to change the structure of museum governance, and the Guerrilla Girls, who used bar charts and information graphics to demonstrate the biases of art institutions. Greenwald cites her scholarly predecessors and situates her analyses squarely within the social history of art, and yet her book represents a radical swerve from this approach’s impetus as well as its effects. She takes the empiricism, but forgoes contextualizing examination, which purges politics from the scene and weakens her arguments as a result. Her categories obscure precisely those patterns and prejudices that historical analysis, driven by data or not, might help us see.

To take seriously the potential of “data-driven art history” also necessitates recognizing the ways that art history has always been data-driven, especially if you detach data from the large scale of social science research. Greenwald’s continued use of the word “patterns” is telling, as it is the same term that nineteenth-century German art historian Heinrich Wölfflin used to describe what he discovered when he practiced formal analysis. With its emphasis on close looking and reading the individual image, formal analysis is a foil for Greenwald, its smallness a clear contrast to the “bigness” of data. And yet, Wölfflin saw the image as a symptom, a means by which to discern the collective dimensions of vision, perception, and experience, and to excavate the social and historical conditions of how and what we see: in short, he used it as an essential tool for analyzing at scale. Formal analysis is an approach that finds social forces in the details of a painting, an important reminder that “society” isn’t visible only at the widest aperture or the furthest remove.

Camille Pissarro: The River Oise near Pontoise, 1873, oil on canvas, 18 by 22 inches. Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Mass.

Camille Pissarro: The River Oise near Pontoise, 1873, oil on canvas, 18 by 22 inches. Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Mass.

Relatedly, it is important to push against the operating assumption that studying more art automatically makes art history more democratic—that expanding the scope of art history is the same as revolutionizing it. This is something Greenwald implies, though her own data set does not enact it. Scholars can and should expand the bounds of art history, to study little-known artists and explore arenas of creative human expression far beyond the limits of conventional art, or art conventionally so-called by those historically able to confer the honor. This imperative, which has long been with us, continues to be urgent and necessary. But it must be paired with an awareness and recognition that art history is the study of sample bias—whatever art is at a particular historical moment, it is an ideological effect. When Nochlin famously asked “Why have there been no great women artists?” in 1971, her answer was not “because we haven’t found them yet” but that the structural conditions necessary for one to be an artist (access, education, time, money, tradition) determined who could enter, or even envision oneself entering, the field in the first place. She called not for solutions—as if it were possible to improve the past—but a more robust, multifaceted accounting of art and its historical contours. Greenwald acknowledges these limitations on who can be an artist and what can be art in one breath, and then alleges to transcend them in the next.

This oscillation—between statistics showing the effects of power and claiming to alleviate them simply through scale—is symptomatic of the condition we find ourselves in today: the effects of power are glaringly apparent, the means to undo them far less so. And yet, this is perhaps where art history can find renewed relevance: art is in many ways the active negotiation of scale. It is situated at the nexus of individual agency and social structures, the crux of creativity and convention, thereby condensing and concretizing those very forces that statistics aim to extract. Consequently, the study of art is poised to offer insights into the operations of power that complicate repeated truisms of structural and social constraint—to show not just that but precisely how supra-individual forces play out at the level of expression, desire, agency, and choice. If there is a future for data-driven art history, then it needs to complicate and thematize scale rather than superimpose it. At the very least, it needs to put aside the idea that the scale of the social is only apparent at the level of data and not detail. It is telling that Greenwald’s idea of data—self-evident in its facticity, steadfast in its objectivity, and inherently more social simply by virtue of being “big”— ends up displacing a real, and much-needed, reckoning with the limits and possibilities of art history with a quick fix. More obfuscates what it might mean to do better.

This article appears in the July/August 2021 issue, pp. 27–29.

Source link : https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/aia-reviews/painting-by-numbers-book-digital-humanities-art-history-1234599617